Last Friday the Supreme Court overturned the doctrine of Chevron deference as part of its ruling in Loper Bright Enterprises v Raimondo. This might not have even been their most discussed ruling of the past week, but in my (non-lawyerly) opinion, there is a good chance it will be their most economically impactful ruling of the past decade. SCOTUSblog explains the basics:

the Supreme Court on Friday cut back sharply on the power of federal agencies to interpret the laws they administer and ruled that courts should rely on their own interpretation of ambiguous laws. The decision will likely have far-reaching effects across the country, from environmental regulation to healthcare costs.

By a vote of 6-3, the justices overruled their landmark 1984 decision in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, which gave rise to the doctrine known as the Chevron doctrine. Under that doctrine, if Congress has not directly addressed the question at the center of a dispute, a court was required to uphold the agency’s interpretation of the statute as long as it was reasonable. But in a 35-page ruling by Chief Justice John Roberts, the justices rejected that doctrine, calling it “fundamentally misguided.”

Justice Elena Kagan dissented, in an opinion joined by Justices Sonia Sotomayor and Ketanji Brown Jackson. Kagan predicted that Friday’s ruling “will cause a massive shock to the legal system.”

When the Supreme Court first issued its decision in the Chevron case more than 40 years ago, the decision was not necessarily regarded as a particularly consequential one. But in the years since then, it became one of the most important rulings on federal administrative law, cited by federal courts more than 18,000 times.

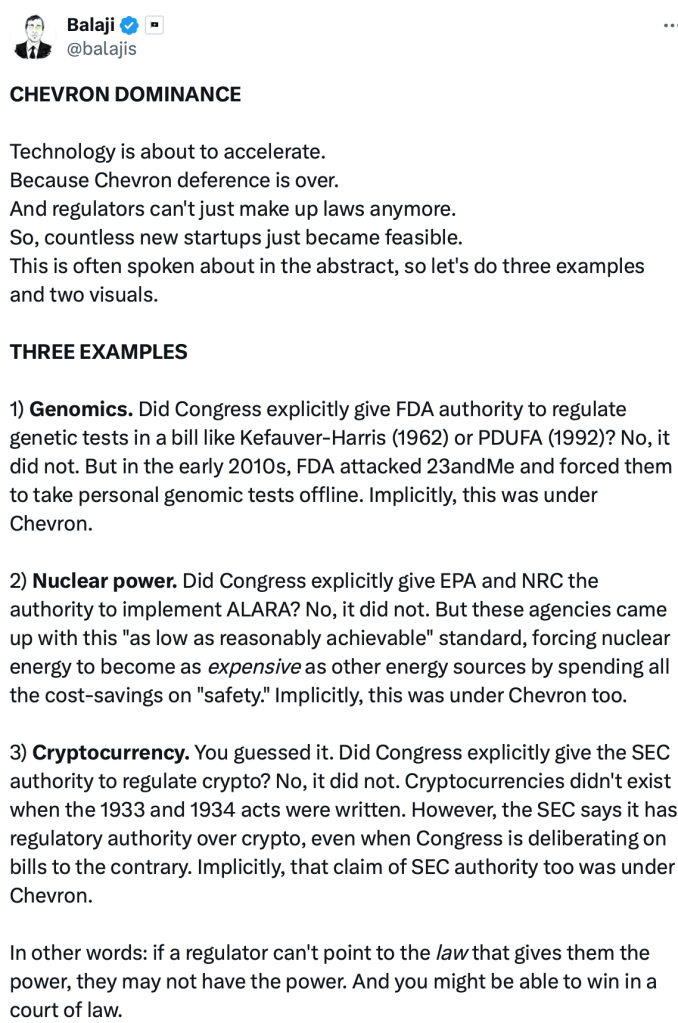

The most common reaction I’ve seen is that people expect this to reduce the power of executive branch agencies, both in general and relative to courts and businesses, likely resulting in deregulation. Thus those on the economic left have been mostly decrying the decisions, while free–marketers and businesspeople have mostly been celebrating:

Still, a substantial minority of the reactions predict that this ruling could actually harm business, or at least have little benefit for them. After all, the original ruling in the 1984 Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council was supporting the oil company Chevron by upholding Reagan-era Environmental Protection Agency’s deregulatory interpretation of the Clean Air Act. We could see more legal challenges to deregulatory actions from agencies, and just generally more legal uncertainty, which business tends to dislike. Business might prefer a strict rule that is clearly the rule, to one that is looser on paper but might lead to years of lawsuits by third parties (though Chevron-empowered agencies didn’t necessarily bring clarity). Or the Loper Bright ruling might end up having little effect, perhaps because courts still defer to the government even when not required to.

Still, I think the more common reaction is mostly the right one. Already a court has stopped the FTC’s proposed ban on non-compete contracts, citing the new standard of Loper Bright. Five or ten years down the road, how will we know what the effects of the new standard are? Lawyers could look at all the major cases citing Loper Bright, and sum up the effect they think it had on them. As an economist, I’d like to have a number to point to. Will there be an inflection point in the number of lawsuits against administrative agencies? Will we see a drop in the number of new agency rules, or regulatory restrictions as measured by RegData? If so, my work suggests we could see faster economic growth. But it isn’t clear that Chevron itself increased regulation after 1984:

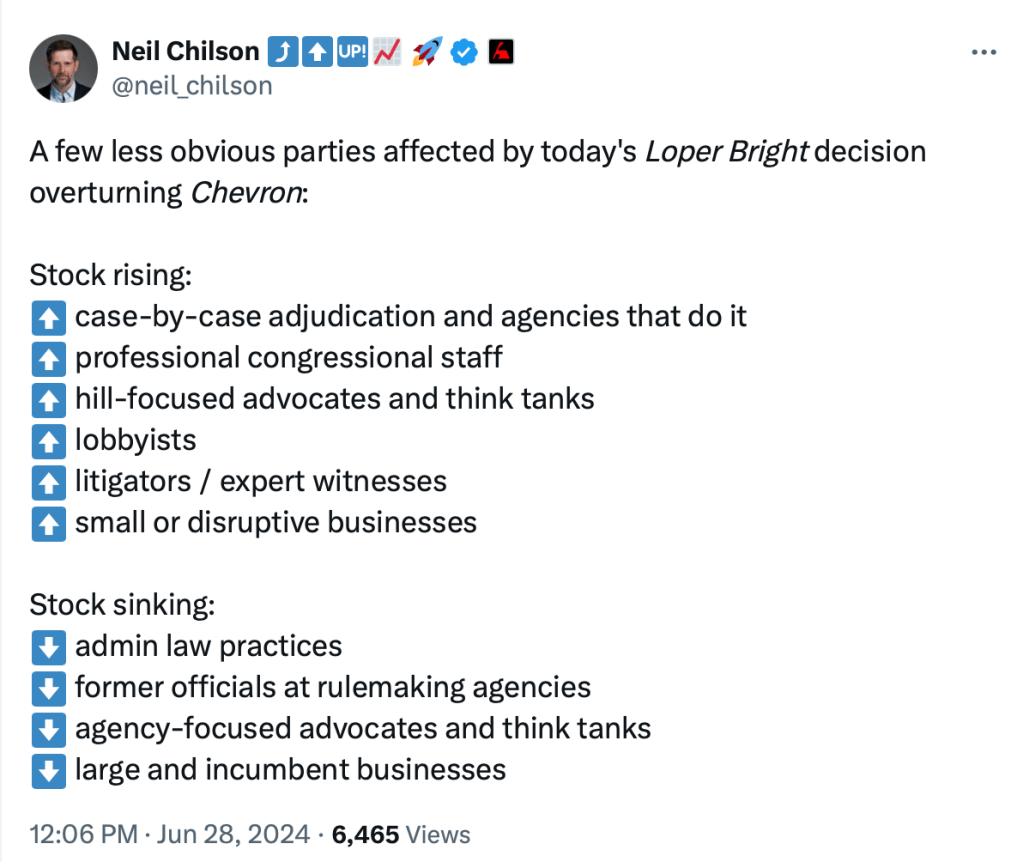

My favorite takes went beyond “ruling good” or “ruling bad” to think carefully about how it can or should change the game going forward. Here’s Neil Chilson of the Abundance Institute:

In Newsweek, Marci Harris and Zach Graves argue that the Supreme Court is trying to hand power from the executive branch back to Congress, but Congress needs to change in order to pick it up:

Absent Chevron, Congress could be forced to be much more specific in how it crafts legislation, delegates authority, and conducts regulatory oversight. If it refuses to adapt, agencies could be incapacitated and service delivery could stall…. a lot will have to change. In the 40 years since Chevron was decided, Congress has seen worsening dysfunction and atrophy. Staffing on House committees has shrunk by 41 percent. Critical support offices like the Congressional Research Service and the Government Accountability Office have downsized by more than 25 percent. Meanwhile, the complexity of the federal bureaucracy has increased immensely.