David Neumark has an excellent article reviewing the extensive literature examining the effects of the minimum wage on, well, a little bit of everything. Sometimes we see improved outcomes, sometimes worse outcomes, often not much of anything. I’m not demeaning this literature to which I’ve myself helped make a modest contribution, but there does arise the concern that perhaps the fruit has begun to hang a bit too low. Which is to say that in a world of modern computing, where regressions can be run at approaching zero cost and policy changes are characterized by an at least a minimally sufficient level of exogeneity, there’s nothing stopping anyone from regressing any measurable outcome on the minimum wage. We’re still arguing about the minimum wage, but what exactly is it that we are learning?

I’m going to head this post off at the pass befores it veers into “back in my day economics used to be about the theory” territory. Yes, the ascendance of empirically-driven applied economics has led to theory to taking something of a backseat, at least in terms of the sheer volume of published research, but I don’t think that is what is going on with the minimum wage literature. Rather, I think its a story of supply and demand.

The minimum wage is an almost perfect issue for people to argue over. It’s not life or death, which keeps the temperature below “brick throwing” levels. The status quo always bears the possibility of change, making arguments policy salient. The absence of action is a meaningful option, particularly in a world with non-trivial inflation. It’s a quantifiable policy that affects incomes and employment directly, which means it’s sufficiently concrete for anyone to have an opinion on. Last, but certainly not least, it lends itself to binary opinion-affiliation in that you either think the minimum wage should be higher or you don’t.

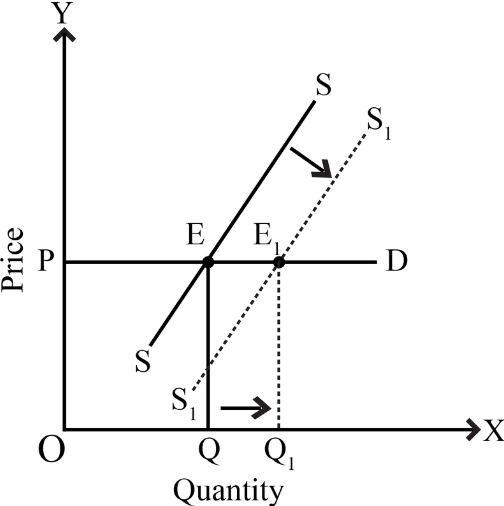

From the point of view of researchers, this adds up to a policy for which there will be near endless research demand. To satisfy that demand your research should, preferably, give consumers a new reason to belief the minimum wage should or should not be higher. To do that a researcher need either i) give new and useful evidence as to how and how much the minimum wage affects earnings and employment, or ii) new and useful evidence that the minimum wage makes some other measurable outcome better or worse. When you consider that the cost of consuming new research is both low and constant, it’s fair to consider the demand to be perfectly elastic. Coupled with the increase in the supply of empirical research generated by reduced cost of computing noted earlier, we shouldn’t be surprised by an equilibrium where an ever-growing number of outcomes have been regressed on the minimum wage.

I don’t think this is anything to get worked up over, don’t see any first-order negative externalities. Most complaints about low-cost empirical research usually sound like academics pining for a time with higher barriers to entry, when you had to be “really good” to produce economic research. The assumption that the complainer is themselves, of course, “really good” always seems to remain unstated. Back to my earlier question, though: what are we learning?

If you’re genuinely curious about the minmum wage, read Neumark’s review. It’s characteristically excellent. Rather than recap, let me come out and say what I think I’ve learned from the reading a lot, but certainly not all, of the minimum wage literature. The minimum wage matters, it’s salient to people earnings, but not nearly as much as the volume of research or argument would suggest. The effects observed tend to be moderate, but labor markets are sufficiently local, heterogenous, and complex that the there remains the possibility of observing different results with different (but largely honest) analyses. This goes doubly so for observing any second-order effects beyond wages and employment, such as health, education, or crime. You are more likely to observed improved outcomes when changes are small, deleterious effects when changes are large.

Those are easy, largely riskless conclusions to share, so let me go a bit farther. The fact that we observe anything but trivial outcomes, positive or negative, is a stark reminder of the margins on which so many people are making decisions. Whether it’s earning a dollar more an hour or losing half a shift a week, it is telling that we see more criminal recidivism, more smoking, less teen-pregnancy, more maternal time with children, and a dozen other effects. It just doesn’t take that much to move the needle.

There is a constant cultural bombardment to value income and material goods less. Perhaps the lesson of a thousand and one minimum wage regressions is that many people aren’t experiencing the diminishing returns to income that popular advice would have you believe. For the young, less-educated, recently immigrated, or those burdened with the stigma of a criminal record, the income elasticity of human behavior remains very much intact. Labor policies matter, even if the minimum wage shouldn’t be quite so close to the top of the list.