Alex Burns recapped a conference session about the market for PhD students in History. It was, predictably, rather despondent as is the nature of the job market for all graduate students in history, but doubly so for those outside the absolutely most elite 3 to 5 schools. The whole thread tells the story of graduate education in history, and the broader humanities, with sincerity and empathy.

Now, if I were a respectable economist, I would note that discussed plans to increase the supply of graduate student labor in a market with already paper thin demand is most certainly not the answer. Economists rarely pass up the opportunity to roll their eyes at any academic failing to understand supply and demand, but fortunately Christopher Jones (a proper historian) already made the appropriate observation:

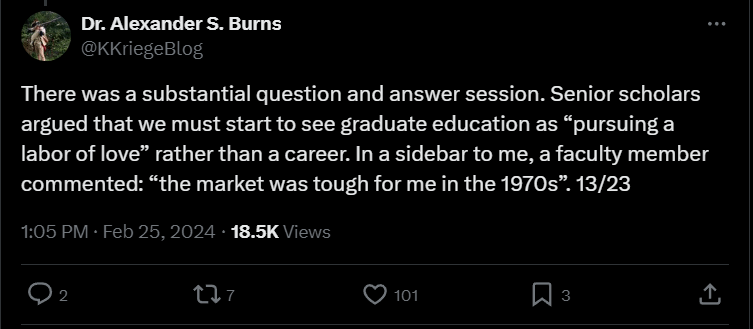

What caught my eye, however, was the noted recommendation that faculty stop identifying scholarship in their field as a viable career altogether:

This makes my blood run cold for a number of reasons. First, its a trap whose bait is appealing to those students who are simultaneously the most earnest and most insecure. Unsure of what life will be like after college but know in your heart that you loved your classes in rhetoric or 16th century literature? Then why not make the noble decision to forsake the material world for a life of the mind? That’s exactly the kind of trap that makes for the pompous 23-year olds who turn into angry and despondent 30 year olds.

Perhaps worse, however, is the forsaking of an entire discipline that once held the mantle of profession and might now resign itselft to the standing of a hobby. I’m a STEM-y, arrogant economist who consumes very nearly no pre-19th century literature but that doesn’t mean I don’t think the deepest understanding of the foundations of a culture, any culture, doesn’t have profound insight to offer future generations. There is value there, the kind that might even qualify as a public good, whose provision we might want to collectively support, if we so chose.

It’s especially frustrating, however, because I can’t help but think the answer is right in front of them. It just happens to be nearly the inverse of the first suggested policy. History and the humanities need to reduce the supply of graduate students. That’s all there is to it. Yes, research and teaching will be more slower and more arduous without as many graduate assistants. It’s a tough break, but it sure as hell seems a more modest price to pay than the abandonment of scholarly training as something that leads to a viable career. I’d also like to very much hope that it would ease the conscience of faculty taking on graduate students as assistants, then thesis advisees, knowing that 5 years of laborious apprenticeship isn’t destined from the beginning to end in tears. You’ll have fewer graduate students, but hey, at least now you’ll be able to look them in the eye.

There’s a term in urban development: shrinking to greatness. A city can in fact shrink in population and still come out the other side viable, even potentially stronger than ever. That’s the story of Pittsburgh. Embrace what you are, not what you used to be or wished you were. There are a lot of disciplines and subdiscplines that are going to destroy themselves trying to become the STEM fields they wished they were or the recreate past golden ages of dubious veracity. But there will be some, across fields or within single universities, who will recharacterize themselves as custodians and curators of scholarship whose demand may have shrunken, at least for the moment, but whose contributions can carry forward. If that means at a slower pace or smaller scale, so be it. Better to embrace what you are than recruit the naive as kindling for a bonfire lit by arrogance and denial.

Good article. Excellent quote: “Better to embrace what you are than recruit the naive as kindling for a bonfire lit by arrogance and denial.”

LikeLike

Thanks!

LikeLike

Usual ripping-good prose from Mike, I liked “…That’s exactly the kind of trap that makes for the pompous 23-year olds who turn into angry and despondent 30 year olds.” But seriously, somehow this ought be be brought to the attention of academic leaders of disciplines like history, or at least tweeted about among undergraduate history majors. Sometimes the obvious is hard to see if you are too close to it, or as Keynes remarked, if your salary depends on you not seeing it.

My impression, and I hope someone fact-checks this, is that up through maybe 1960, the folks getting graduate degrees in the humanities largely came from monied families, and so did not really need to worry about earning their daily bread by working in their fields. And/or the university system was still expanding, so there were in fact plenty of jobs for newly minted PhDs.

It is a different world now, and world in which, incidentally, if you wish to learn about any aspects of history, there are on-line classes or free YouTube lectures that can take you pretty much as far as you want to go. So the necessity of grinding out a PhD thesis in order to partake of the glories of the past has largely gone away.

LikeLike