Let’s talk game theory. I’ve written in the past about Pure Strategy Nash Equilibria (PSNE). They identify possible equilibrium strategies, even if players are unlikely to adopt those strategies in real life. Students don’t like the implausibility of many PSNE strategies, and they sometimes struggle to limit their conclusions to the premises that yield PSNE. Students have a similar dissonance to Mixed Strategy Nash Equilibria (MSNE).

What is MSNE? A set of MSNE strategies allow a player to choose some strategies probabilistically – with probabilities that are less than 100%. That’s the feature of MSNE that distinguishes it from PSNE. In PSNE, a strategy is chosen with 0% or 100% probability.

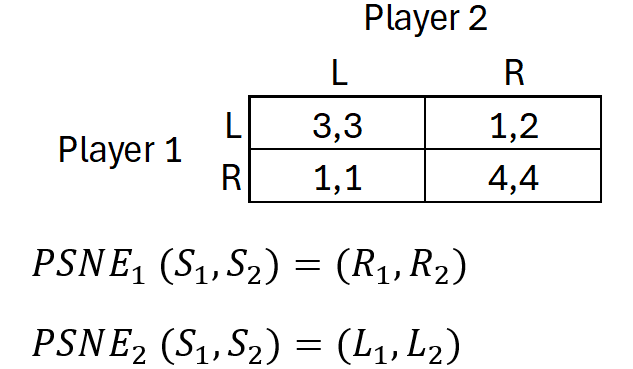

Here’s an example to illustrate. Imagine that you are shopping at the grocery store with your shopping cart. You’re at one end of the aisle and another shopper is at the other end and your heading straight toward one another at a snail’s pace. Ideally, you’d not hit each other or awkwardly arrive in each other’s path. For simplicity, let’s say that each of you can walk on the right or the left side of the aisle only.* Below is a simultaneous normal form game with arbitrary payoffs.

There are two PSNE in the above game: each person walks on their right or their left side of the aisle. If you and the other person are both walking on your respective rights or lefts, then neither of you has an incentive to deviate. The alternative is that you are heading straight for one another and one of you must veer from their path or play an awkwardly low stakes game of chicken.

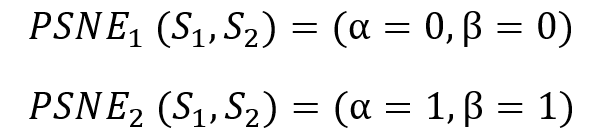

Having no incentive to deviate is what makes the PSNE strategies Nash equilibria. Choosing strategies with 100% or 0% probability is what makes the PSNE strategies ‘pure strategies’. Let’s use some Greek. If α is the probability that player 1 chooses L, and β is the probability that player 2 chooses L, then we can express the PSNE strategies with the below notation and the meaning is unchanged.

Introducing MSNE

Now that we have expressed the decision to choose left probabilistically, we are no longer limited to just left or right with certainty. Now we can choose left with any of the infinite number of possible probabilities between 0 and 1. I’m sorry folks, but we’re about to get mathy.

Symbolically, π refers to a player’s payoff. That’s the joy/satisfaction/utility that a player experiences. Once players choose to play probabilistically, we are no longer discussing payoffs that are guaranteed. Instead, we’re discussing *expected payoffs* that are a weighted average of the possible outcomes. Truly, even the payoffs that result from PSNE strategies are just special cases of expected payoffs.

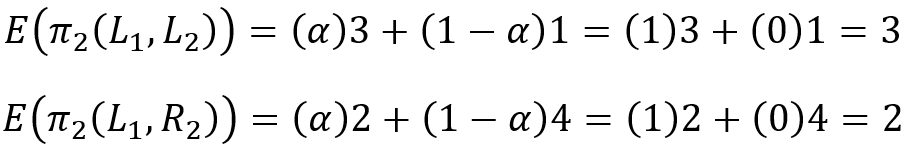

Here is an example. Let’s assume that player 1 chooses L. Below are two equations, one identifies the expected payoff for player 2 if they choose L, and the other is the expected payoff if player 2 chooses R.

Clearly, the expected payoff for player 2 is higher if they choose L. Therefore, we conclude that if player 1 chooses L, then player 2’s best choice is to also choose L.

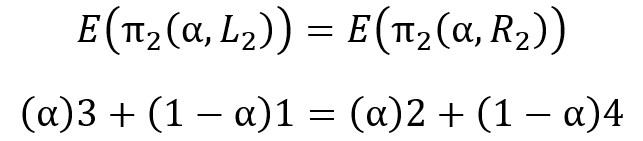

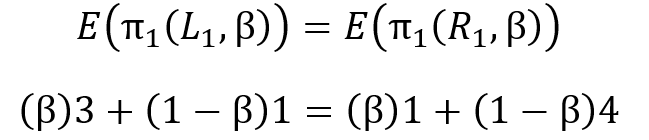

Can the players choose α and β other than 0 or 1 and still arrive at a Nash equilibrium (choosing neither 0 & 1 values is called ‘mixing’)? Let’s find out. Again, a Nash equilibrium requires that neither player has an incentive to deviate from their current strategy. Let’s see if player 1 can choose a value of α in order to give player 2 no incentive to deviate from his own mixed strategy. The only case in which player 2 can mix and have no incentive to deviate is when his expected payoffs are identical between his pure strategies. Indeed, if the expected payoffs are identical, then any strategy that he chooses, pure or mixed, results in the same expected payoff. Here’s the math:

The first line says that player 2’s expected payoffs of choosing L or R are identical. Using the second equation, we can solve for the α that causes the equation to be true. Skipping the algebra, the answer is α=0.75. At that value of α, player 2 has the same expected payoff when they choose L or R. What’s more, if player 2 chooses to mix, then the expected payoffs are the same at *all values of β*. What does this mean? This means that player 1 can choose a specific alpha in order give player 2 no incentive to deviate. Nice.

We have not found an MSNE yet. If player 2 adopts a pure strategy of L or R, then player 1 would be unwilling to mix. As we said at the top, the equilibrium response to player 2’s pure strategy is another pure strategy.** Well, if player 2 is indifferent among any value of β, then is there a specific value of β that could cause player 1 to adopt α=0.75 as his best strategy? He follows the same process:

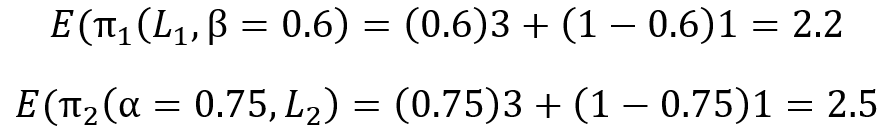

Again skipping the algebra, we find that player 1 is indifferent between L and R when β=0.6. So, *if* player 1 chooses α=0.75 and player two chooses β=0.6, then neither player has an incentive to change their value of α or β. If both players have adopted strategies from which there is no incentive to deviate, then we have found an MSNE! Below is the notation for the MSNE strategies.

Cue the student incredulity. If either player deviates, then the equilibrium falls apart and we might find ourselves at a PSNE. But the same is true of any PSNE. If a player inexplicably deviates, then the other player may change their strategy too. In that regard, MSNE is not sensitive or unlikely. Then students like to ask “But why would players do this?”. The answer to that is an unsatisfying “I don’t know”. Neither MSNE or PSNE tell us ‘why’. They only tell us the set a possible Nash equilibria, not what is plausible or most likely. The fact remains that there is no incentive for either player to deviate if they’ve chosen the MSNE strategies. That’s it, we’re done!***

Putting the math back into the context of the game, the MSNE tells us that choosing L a majority of the time is a possible equilibrium even though we would all be better off if we always walk on the right. How is that sensible? Well, if you’re at the grocery store and you turn the corner of the aisle and observe a player 1 walking on the left 75% of the time, then all of the player 2s can respond by walking on the left 60% of the time – and no one would have a desire to change their ways given the strategies of the people around them. Given that we all know that walking on the right is clearly superior, mixed strategy analysis can help to explain why we don’t always do it (while being rational the whole time).

*I’m omitting the possibility of someone walking obliviously and antisocially down the center of the aisle.

**This is not always true. In some games it’s possible for one player to adopt a pure strategy while the other mixes.

***As an exercise, we can also calculate the MSNE expected payoffs. Since the expected payoffs of any strategy are identical at the MSNE, it makes no difference if we calculate the expected payoff of choosing left or right or mixing.

One thought on “MSNE Echoes PSNE”