A recent post from the blogger (Substacker?) Cremieux called Rich Country, Poor Country showed how small differences in economic growth add up over time. Because he used nominal GDP growth rates, I don’t think that post is exactly the right way to analyze the question, but I still think it’s a very important one. So in this post I will offer, not necessarily a critique of that post, but perhaps a better way of looking at the data.

For the data, I will use the Maddison Project Database, which attempts to create comparable GDP per capita estimates for countries going back as far as possible… for some, back thousands of years, but for most countries at least the last 100 years. And the estimates are stated in modern, purchasing power adjusted dollars, so they should be roughly comparable over time (if you think these estimates are a bit ambitious, please note that they are scaled back significantly from Angus Maddison’s original data, which had an estimate for every country going back to the year 1 AD). The most recent year in the data is currently 2022, so if I slip up in this post and say “today,” I mean 2022, or roughly today in the long sweep of history.

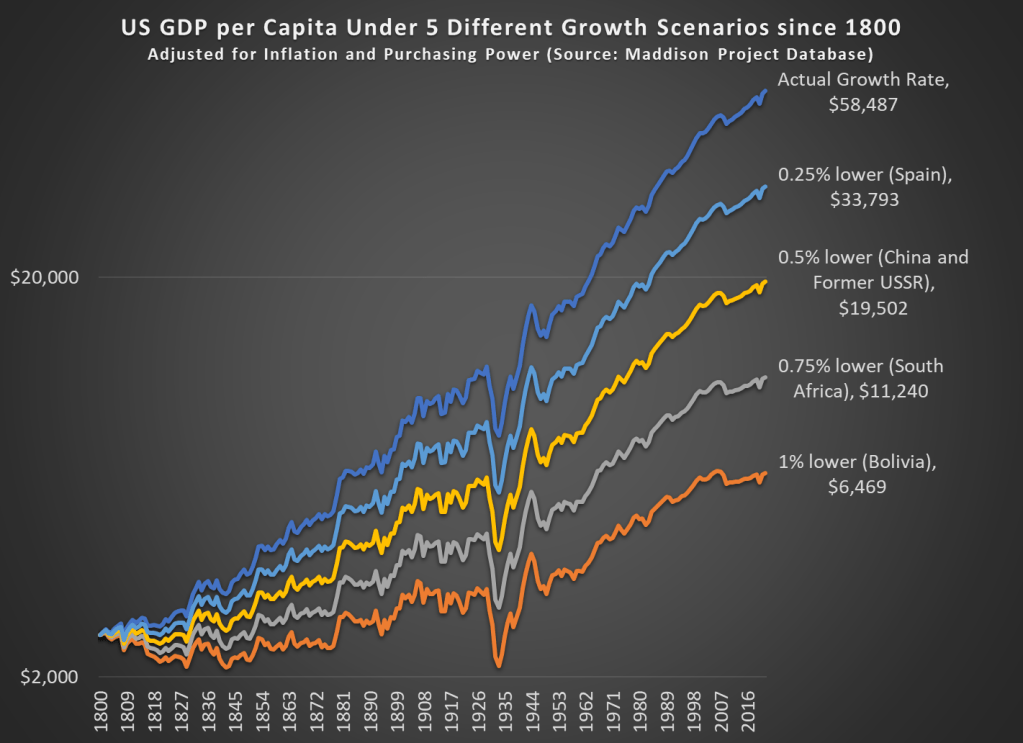

Like Cremieux’s post, I am interested in how much slightly lower economic growth rates can add up over time. Or even not so slightly lower growth rates, like 1 percentage point less per year — this is a huge number, because the compound annual average growth rate for the US from 1800 to 2022 is 1.42%. So let’s look at the data way back to 1800 (the first year the MPD gives us continuous annual estimates for the US) to see how changes in growth rates affect long-term growth.

It probably won’t surprise you that if our 1.42% growth rate had been 1 percentage point lower, the US would be much poorer today, but to put a precise number on it, we would be about where Bolivia is today (that is, ranked 116th out of the 169 countries in the MP Database). Note: I’m using a logarithmic scale, both so it’s easier to see the differences and because this is standard for showing long-run growth rates.

What is very interesting, I think, is that if our growth rate had been just 0.25 percentage points lower per year since 1800, we would be about where Spain is. Now, Spain is certainly a fine, modern developed country (they rank 34th of the 169 MPD countries). But Spain’s growth has not been spectacular lately. Average income in Spain is almost half of the US today (purchasing power adjusted!), which is another way to say that just 0.25 percentage points lower over 222 years reduces your growth rate by half.

That’s the power of economic growth.

And if our growth rate had been 0.5 percentage points lower, we’d be about where the big former Communist countries are today (both China and the former countries of the USSR are about equal today — about 1/3 of the income of the US).

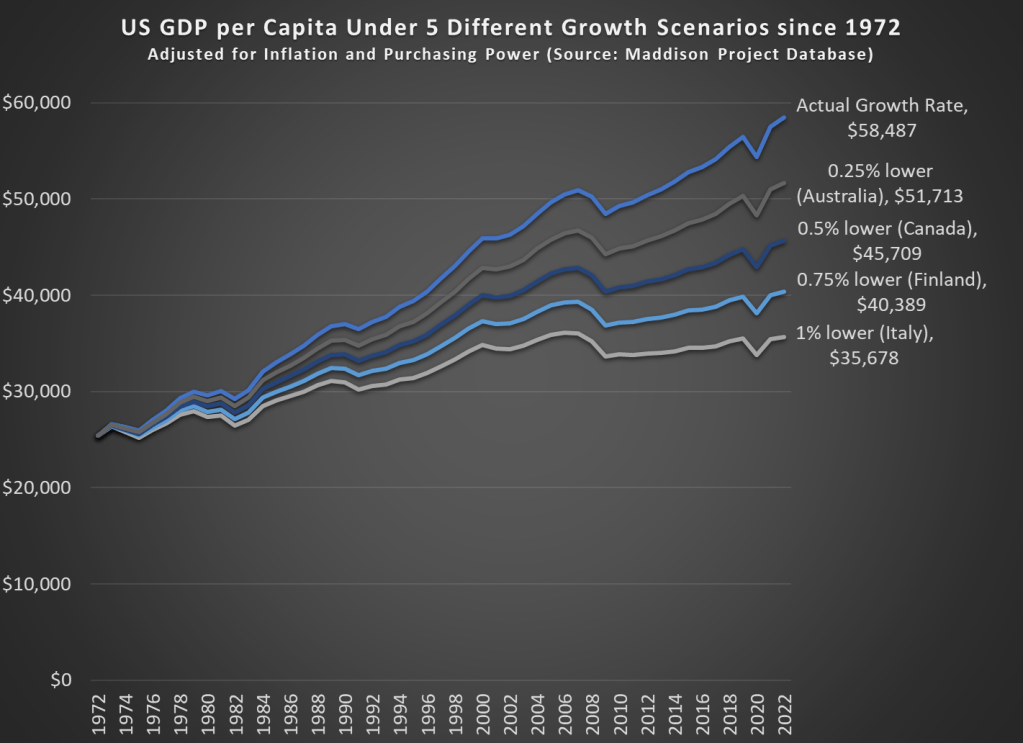

What if we perform the same analysis for a shorter time horizon? If we go back 50 years to 1972, the effects are not quite as dramatic, but still visible.

Our cumulative annual growth rate since 1972 has been a bit higher than the long-run average, around 1.68%. Under these four alternative growth scenarios since 1972, the comparable countries don’t sound so bad. It probably wouldn’t be a huge deal if we were only at Australia’s level, losing just about a decade of economic growth. But it would be a huge failure if we were only at Italy’s current level of development. Under that 1 percentage point lower growth scenario, we would have had no net growth since about year 2000, which has roughly been the case for Italy.

All of these alternative scenarios show the power of economic growth to add up over time, but they do so in pessimistic way: what if growth had been slower. What if we look at the opposite: what if growth had been faster over some time horizon. Sticking with the 1972 medium-run example, if real growth rates had been 1 percentage point higher, our income today would be almost double what it actually is, about $95,000 compared with the current $58,000 (the MPD data is stated in 2011 dollars, so that sounds lower than it actually is now: over $80,000).

What if we went back even further? If our economic growth rate since 1800 had been 1 percentage point higher every year, our average income in 2022 would be an astonishing $517,000 — almost 10 times what it actually was in 2022. That’s a dizzying number to think about, and maybe that’s not a realistic alternative scenario.

But what if it had only been 0.25 percentage points higher since 1800 — that probably is a world that was possible. In that case, GDP per capita would be about double what it actually was in 2022, at over $100,000 (again, stated in 2011 dollars).