There’s so much to say about interest rates. Many people think about them in the context of whether they should refinance or in terms of their impact on borrowing. But interest rates also matter for production beyond impacting loans for new productive projects. Interest rates aren’t just a topic for debtors.

Interest rates impact all production that takes time. That’s the same as saying that interest rates affect all production – but the impact is easier to see for products that require more time to produce.

There’s this nice model called ‘Portfolio Theory’. Taken literally, it says that everything you own can be evaluated in terms of its liquidity, the time until it will be sold, its expected returns, and the volatility and correlation of those returns. Once you start to look at the world with this model, then it’s much easier to interpret. Buying a car? That’s usually a bad investment. It’s better to tie up a smaller amount of money into that depreciating asset rather than to let a larger sum of money experience dependably negative returns. Of course, this assumes that there are alternative uses for your money and alternative places to invest your resources – hopefully in assets with growing rather than decaying value. People often recommend purchasing used cars rather than new cars. Both new and used cars are bad investments and you can choose to invest a lot or a little.

Producers make a similar calculation. All kinds of things motivate them: love, tradition, excellence… But everyone responds to incentives. Consider vintners. They might be a farmer of grapes and a manufacturer and seller of wine. They might like to talk about nostalgia, forward notes, a peppery nose, and other finer things. But even they respond to prices and opportunity cost.

Enter the interest rates.

Everyone faces an opportunity cost. Vintners can choose to tie-up their resources in grapes and vines, or they can sell it all and invest in the US treasuries. Of course, the former has some non-pecuniary benefits. I’m not ignoring those. But if the prices of grape-related products fall adequately or if treasury yields are high enough, then the vintner may cease to hold his title and instead become a run of the mill investor.

Why do vintners make wine? Why not just sell the grapes? Romance aside, it has everything to do with the rate at which grape juice increases in value and becomes the wine that people are willing to pay for. Adjusting for risk, it only makes sense to make wine if the value grows faster than the alternative. If US treasury yields are at, say, 5% per year, then the value that’s tied up in fermenting grape juice needs to grow by at least 5% in order to make sense for the vintner’s portfolio of assets. Once the value of wine starts to grow as slowly as treasury yields, vintners bring the wine to market.

That’s why a lot of wine is only two years old. The price of a three-year-old bottle would need to be another 5% higher than the price of a two-year-old bottle*. Premium brands tend to include a premium price and less volume. Those two things are related. Either a vintner can aim for the premium rating and the higher price (and maybe fail), or they can re-invest in younger wines whose values grow more dependably in excess of 5%. Failure at producing older wines means selling at a price that is less than 5% higher than a younger bottle of wine and resources that could have been growing faster elsewhere.

Rates of return or interest rates are the opportunity cost of resources over time. If the opportunity cost of resources rises, then vintners will sell more young bottles of wine. If the opportunity cost of resources falls, then we’ll see older bottles of wine on the shelves. When interest rates are low, the price of a three-year bottle of wine can have a lower price and its value can still grow faster than the next best investment.

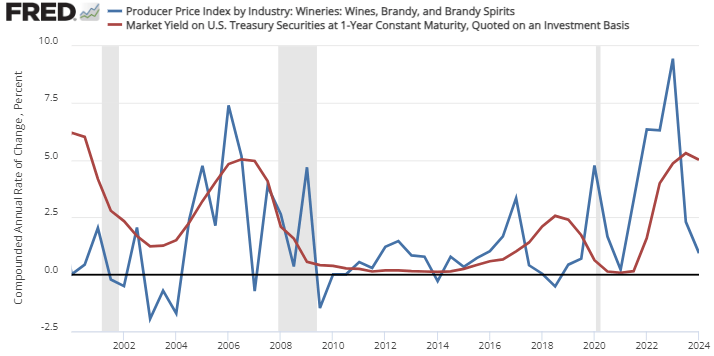

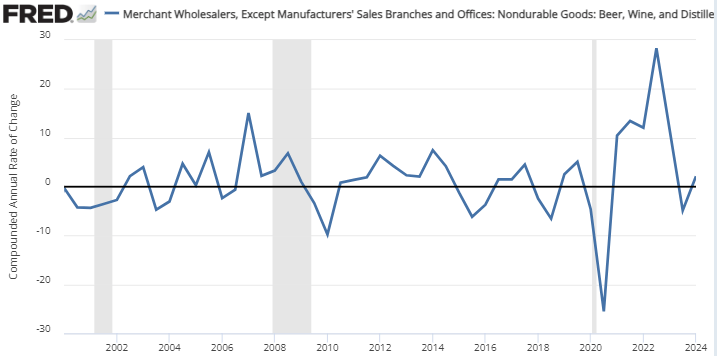

When interest rates rise, vintners sell off their older stock whose value is growing too slowly. Below is the growth rate of the producer price index for wines, brandy, & spirits and the yield on the 1-year US treasury. They tend to rise and fall with a lag. Of course, US treasury yields and the wine PPI both correspond to demand for goods and services. When the Federal Reserve raises rates, it puts downward pressure on the price of consumer goods – including wine. But they also correspond to supply. The second graph below is the inventory-to-sales ratio for beer, wine & spirits. When the price of alcohol goes up, so does the inventory. This tells us that it’s not just demand that’s driving the prices. When the price rises, implying a higher rate of return, suppliers hold more stock so that it too can grow in value. Holding stock implies that the wine is getting older. Once the interest rises however, inventories start to decline as the older wine is pushed out the door.

Interest rates govern the world around us. They help determine saving and lending decisions. But they also determine the age of the wine that we buy and the price difference between a 3-year and a 2-year-old bottle of wine. Interest rates tell us when to make wine, when to sell grapes, and when to get out of the industry entirely.

*US treasuries may not be the appropriate opportunity cost asset. Insert your preferred asset and you’ll get the same results.