I’ve got a new working paper circulating.

“Better Stealing Than Dealing: How do Felony Theft Thresholds Impact Crime?” by Stephen Billings, Michael Makowsky, Kevin Schnepel, and Adam Soliman.

The abstract:

“From 2005 to 2019, forty US states raised the dollar value threshold delineating misdemeanor and felony theft, reducing the expected punishment for a subset of property crimes. Using an event study framework, we observe significant and growing increases in theft after a state reform is passed. We then show that reduced sanctions for theft have broader effects in the market for illegal activity. Consistent with a mechanism of substitution across income-generating crimes, we find decreases in both drug distribution crimes and the probability that a released offender previously convicted of drug distribution is reincarcerated for a new drug conviction.”

For those interested in a bit more of the nitty-gritty, we analyze both arrest and recidivism data within a stacked event study because we are dealing with staggered (diffent years) and fully-absorbing treatments (i.e. once they raise it they never lower it back). States raise their felony theft thresholds for a portfolio of stated and unstated reasons, but the reality is that the value of the marginal stolen good is often deteriorated by decades of inflation only to be doubled or tripled by a single act of legislation. This makes for an excellent before/after experimental setting to test the effect on crime.

We’re going to look at two things broadly: arrests and recidivism. The importance of arrests is straightforward: they give us a sense of the rates of crime across populations. Recidvism is more subtle. More on that in a bit.

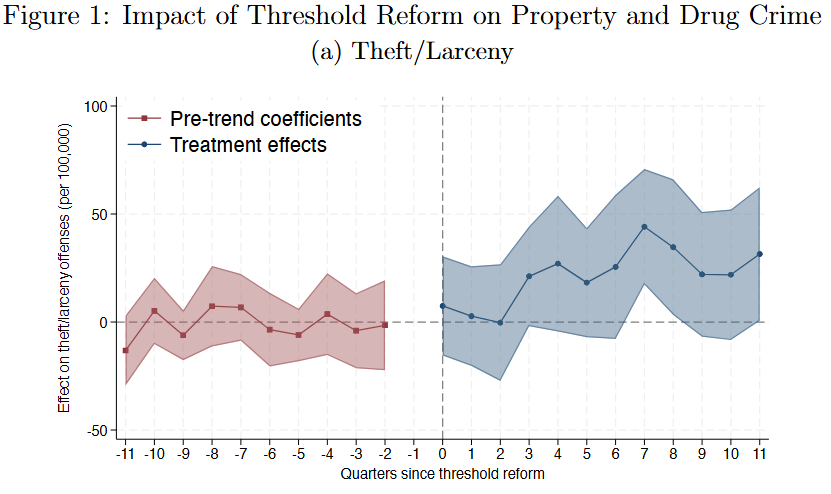

In the quarters leading up to a threshold change (above) we see flat pre-trend with a coefficient of zero i.e. nothing happening. Nothing happening is good, it means that neither law enforcement nor criminals exhibit any sign of anticipating the change. Once a given state makes the change, we see an uptick in rates of theft within 6 months that persists for three years. Speculating beyond that is dangerous – too many other things happening in the world. But criminals seem to be responding.

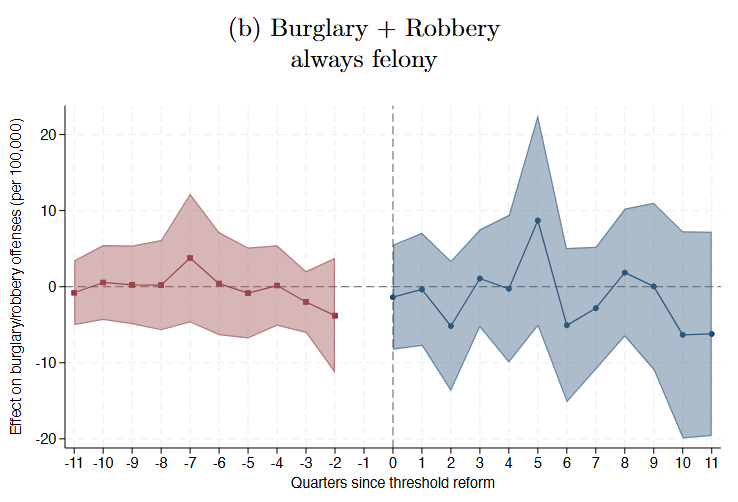

We don’t see any effect on Burglary or Robbery, however (below). This is also a sign of rational criminals since these thresholds don’t apply (i.e. they are always a felony, regardless of property value). In other words, we don’t see an effect on all property crime, just on those crimes for which expected punishment is reduced.

We do, however, see an interested effect on drug distribution (below). In the quarters after a theft threshold reduction, we see a significant and persisting reduction in drug arrests. Yes, we include controlling covariates for medical and recreational marijuana legalization. There’s something else going on here. Are people exiting one income-generating crime for another?

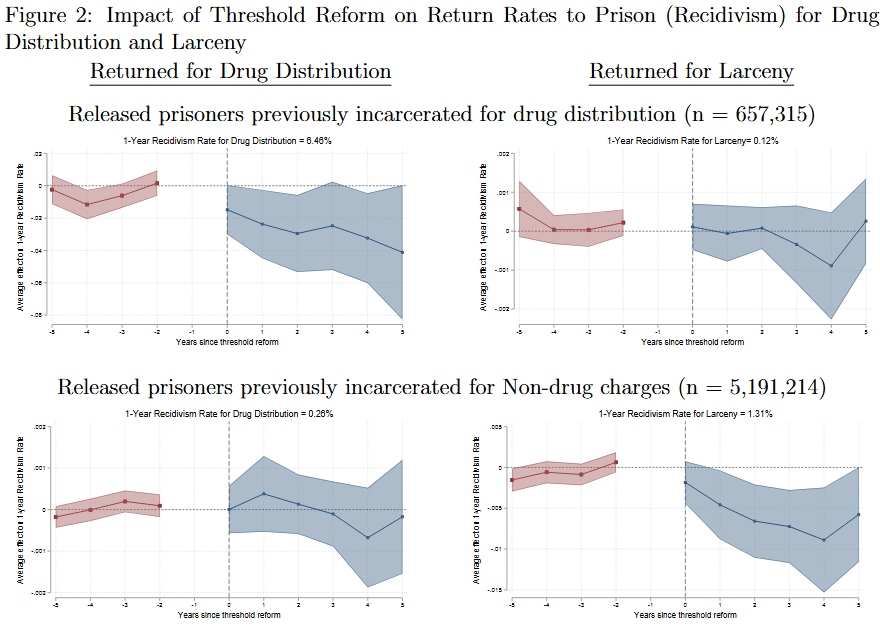

This is where recidivism comes in. Using detailed, restricted-access, prisoner records, we track when prisoners are released and if/when they are returned to prison. By stratifying the analysis by the crime types they were previously incarcerated for, we can separately estimate the effects of felony threshold changes on individuals with human and social capital in the drug distribution business from those who do not. What we observed is both striking and subtle.

For indidividuals previously incarcerated for drug distribution (top left), their rate of return for future drug convictions is immediately lower with a reduction in the felony threshold. For those who were never in the drug trade, there is no effect (bottom left). Reducing the expected punishment for theft is pulling individuals out of the drug business.

Now let’s look at the return rate for felony larceny. For most prisoners (bottom right), there is a massive reduction in the rate of return for larceny. This makes complete sense – if more theft is classified as a misdemeanor, you are much less likely to be re-incarcerated with a new sentence for it. When we look at prisoners previously incarcerated for drug distribution, however, there is no observed effect (apologies for the changing y axis scales, there’s no good way to keep them constant). What does this mean? We interpret this as evidence that the reduction in punishment for theft is canceled out by the shift into theft as a preferred way of earning income. The labor substitution effect cancels out the effect of reduced punishment.

There’s obviously a lot more in the paper. No, there is not an effect on violent crime (Table 2). No, there is not an observed effect on officer enforcement intensity (Appendix Table A3). No, we can’t do a regression discontinuity at the threshold values (too much bunching, see Appendix Figure A7). The conclusions are both obvious and subtle, but the most important may simply be the reminder that all policies have tradeoffs and spillovers, no matter how narrow they might seem.

TLDR; When states increase the property value threshold delineating misdemeanor from felony theft, prospective criminals respond by a) committing more theft and b) substituting out of drug distribution and into theft. This pattern of substitution in the criminal labor market is more evidence that criminals are not only rational and respond to deterrence incentives, but are also selecting across criminal options, which means we should expect spillovers across crimes when policies create differential changes in expected punishments, enforcement, and returns.