If you didn’t know, China has had negative population growth for the past 4 years. Japan has had negative population growth for the past 15 years. The public and economists both have some decent intuition that a falling population makes falling total output more likely. Economists, however, maintain that income per capita is not so certain to fall. After all, both the numerator and denominator of GDP per capita can fall such that the net effect on the entire ratio is a wash or even increase. In fact, aggregate real output can still continue to grow *if* labor productivity rises faster than the rate of employment decline.

But this is a big if. After all, some of the thrust of endogenous growth theory emphasizes that population growth corresponds to more human brains, which results in more innovation when those brains engage with economic problems. Therefore, in the long run, smaller populations innovate more slowly than larger populations. Furthermore, given that information can cross borders relatively easily no one on the globe is insulated from the effects of lower global population. Because information crosses borders relatively well, the brains-to-riches model doesn’t tell us who will innovate more or experience greater productivity growth.

What follows is not the only answer. There are certainly multiple. For example, recent Nobel Prize winner Joel Mokyr says that both basic science *and* knowledge about applications must grow together. That’s not the route that I’ll elaborate.

Instead, I’m thinking about labor rigidities. Just like mobility in where people live geographically, workers tend to have a bit of lethargy or stickiness when it comes to switching employers (and jobs). After all, a new job might require a change in location, uprooting family and wiping out established positional goods. So, an employee may only switch jobs if there is a compensating differential. Not only must the new job compensate more, but the new job must compensate for whatever the employee foregoes by adopting the new job. The same logic applies when someone intentionally switches to a job of lower pay – they usually gain something else, such as leisure, relaxation, flexibility, etc. But in this case too, the difference in what is gained must be adequate to compensate for what was lost by leaving the prior job (though, mistakes happen).

Given that there is uncertainty involved in changing jobs, the expected value of switching is viewed with some risk, and the risk premium of the new job must compensate the worker for bearing it. This is a big reason why people switch jobs when the compensation difference is big rather than small. A small increase in pay may not reward an employee adequately to forego positional goods or to adopt the risk associated with joining a new firm. Colloquially, the old firm is the devil you know.

Let’s return to who will experience faster productivity growth. Imagine that there is stickiness in the labor-employer relationship that fits the description above. People change jobs, but only if the compensation difference exceeds some delta. For the moment, let’s assume that delta is really big. Then what?

If there are two industries whose compensation differs by less than delta, then employees don’t switch jobs. You might think that this economy is doomed to inefficiency. But, there’s good news. Every year, a batch of new adults age into the workforce and an old batch of workers age out. Even without workers changing jobs, the new workers entering where the wage is higher helps to allocate scarce labor where it is most productive. Assuming similar attrition rates at retirement, the more productive industry will compose an increasing share of the economy and the labor force, increasing the average labor productivity. The new workers trickling in are the marginal workers who do the equilibrating.

Now let’s reduce the population growth rate. There are fewer workers entering the two industries, causing more persistent wage gaps and slower equilibration. Every year of persistently larger gaps in marginal productivity is a year of lower output and smaller increments of output growth. In fact, it may happen that the attrition rate exceeds the rate at which new adults join the workforce. In this case it’s possible that both industries experience shrinking workforces, but the less productive just shrinks faster since the precious few new workers join the more productive industry.

Let’s extend the logic to many sectors and a less extreme delta. With a high delta, population growth matters a lot because it’s what’s doing the equilibration in labor markets and increasing the relative size of the high productivity industries. But with low deltas, employees change jobs easily and readily, reducing the importance of new working adults. Instead of the new workers predominantly equilibrating the labor market, the existing workers do it. The result is that employment in low productivity industries shrink, high productivity industries grow, and the labor of the country becomes more productively allocated more quickly. This quick adjustment to more productive industries increases RGDP per capita and may even increase aggregate output.

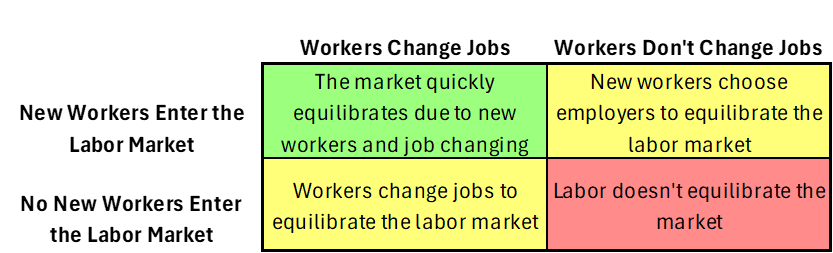

We can illustrate the possible states of the world with a 2×2 matrix. Throughout the 20th century, we lived in the top row. The USA lived generally toward the top left corner, while France and Italy lived toward the top right corner. I say ‘toward’ because the matrix is a simplification. Of course, there is a continuum of the degree of new market entrants and job switching. Now that countries have slower or negatively growing populations, their labor markets are further down in the below matrix. Losing access to as many new workers here in the 21st century makes relatively free and liquid labor markets more important. Whether a country grows faster in the upper-right or lower-left corner is an empirical matter. But, all else constant, being further down or to the right makes for a more slowly equilibrating and more slowly growing economy.

I’ll save the empirical exercise for another time. Of course, since this post is largely abstract rumination, it’s possible to be wrong in more than one way. For example, I’ve excluded the possibility that the lower productivity industry ceases to exist, or that non-labor allocations equilibrate the markets. I’ve also excluded people leaving the geographic area, though that may be the same as mid-life attrition. Please let me know your thoughts in the comments.

PS: Really, liquid markets improve allocative efficiency and make minds attentive to the high productivity tasks. So, better allocating markets clearly have improved welfare in static analysis. But one could easily argue that economic growth is a result of repeatedly adopting one-time innovations. That’s a common perspective and consistent with the above.

“Therefore, in the long run, smaller populations innovate more slowly than larger populations.” This is out of date. Endogenous growth theory does not account for AI which is vastly expanding the number of “brains”.

LikeLike

We’ll see! 1) Those brains need to be directed. Analogous to capital and labor (both of which enter the technology production function). AI seems relatively well encapsulated by EGT. 2) It’s also TBD how well AI will function outside of digital space where iterations are more expensive. 3) Assuming your right about the relevance of AI, and I suspect that you are, you’ve just changed the scarce input and not addressed the logic. Replace all the ‘labor’ words with ‘AI’, ‘robots’, or ‘energy’ and it’s all still sensible.

4) the post explicitly says that the EGT framework is not what I describe.

LikeLike

Interesting issue. I have seen commentary that the US is heading into a big white collar/blue collar mismatch: Nvidia CEO tells us half of the professional jobs will be going away, but we are short on steelworkers and electricians to build the data centers to make that happen. We are talking huge retraining and physical relocations here (e.g., moving around to next construction job). Even more, a seismic shift in expectations – – being out in the cold and the heat, climbing around girders with a hard hat, vs. sitting in air conditioned office poking a keyboard. (In my career I had to climb up outside and inside of big refinery units once, and that was enough for me).

Also, completely different subject: Zach, I think some years ago you wrote a post here discussing ways to save money, including buying glasses online. I searched but could not find that article. Could you post the link in a reply here? Thanks

LikeLike

Re white-collar-emptying: We’ll see!

I also can’t find one that I wrote about saving money. But James wrote one about vision insurance and I think that it included online glasses purchases.

LikeLike