The confluence of politics, recent interest in agent-based computational modeling, and Pluribus have convinced me now is the time to write about the “Cooperative Corridor”. At one point I thought about making this the theme of a book, but my research has become overwhelmingly about criminal justice, so it got permanently sidelined. But hey, a blog post floating in the primordial ether of the internet is better than a book that never actually gets written.

It’s cooperation all the way down

Economic policy discussions are riddled with “Theories of Everything”. Two of my favorites are the “Housing” and “Insurance” theories of everything. Housing concerns such huge fractions of household wealth, expenditures, and risk exposure that the political climate at any moment in time can be reduced to what policy or leader voters think is the most expedient route to paying their mortgage or lowering their rent. Similarly, the decision making of economic agents can, through a surprisingly modest number of logical contortions, always be reduced to efforts to acquire, produce, or exchange insurance against risk. These aren’t “monocausal” theories of history so much as attempts to distill a conversation to a one or two variable model. They’re rhetorical tools as much as anything.

My mental model of the world is that it is cooperation all the way down. Everything humans do within the social space i.e. external to themselves, is about coping with obstacles to cooperating with others. It is a fundamental truth that humans are, relative to most other species, useless on our own. There are whole genres of “survival” reality television predicated on this concept. If you drop a human sans tools or support in the wilderness, they will likely die within a matter of days. This makes for bad television, so they are typically equipped with a fundamental tool (e.g. firestarting flint, steel knife, cooking pot, composite bow, etc) after months of planning and training for this specific moment (along with a crew trained to intervene if/when the individual is on the precipice of actual death). Even then, it is considered quite the achievement to survive 30 days, by the end of which even the most accomplished are teetering on entering the great beyond. No, I’m afraid there is no way around the fact that humans are squishy, nutritious, and desperately in need of each other. Loneliness is death.

Counterintuitive as it may be, this absolute and unqualified dependence on others doesn’t make cooperation with others all that much easier. This is the lesson of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, that our cooperation and coordination isn’t pre-ordained by need or even optimality. Within a given singular moment it is often in each of our’s best interest to defect on the other, serving our own interests at their expense.

Which isn’t to say that we don’t overcome the Prisoner’s Dilemma every day, constantly, without even thinking about it. Our lived experience, hell, our very survival, is evidence that we have manifested myriad ways to cooperate with others despite our immediate incentives. What distinguishes the different spaces within which we carry out our lives is the manner in which we facilitate these daily acts of cooperation.

Kin

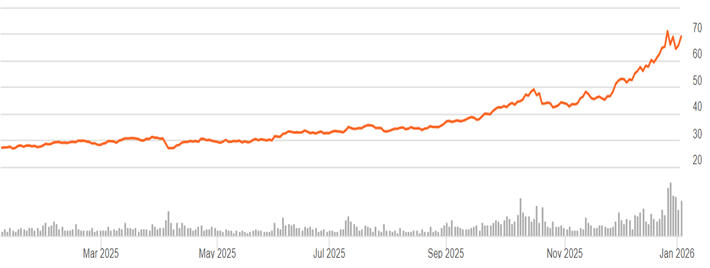

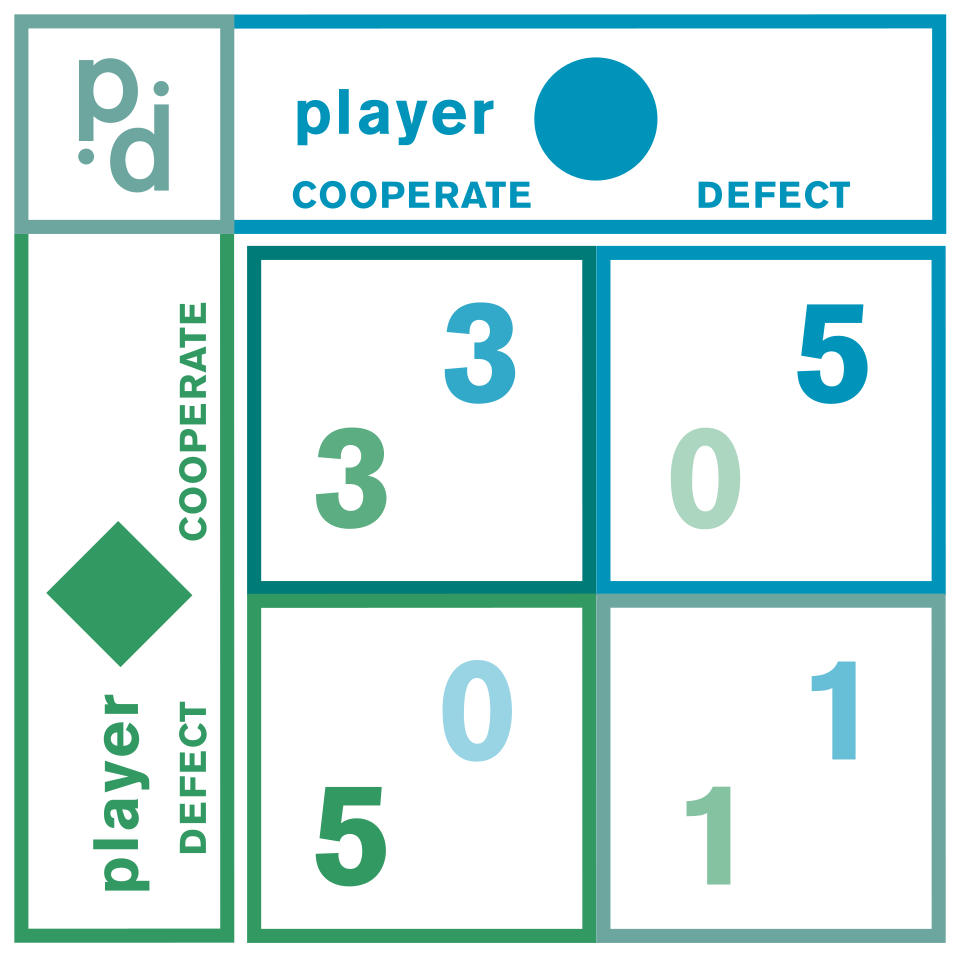

The first and fundamental way to solve the prisoner’s dilemma is to change the payoffs so that each player’s dominant strategy is no longer to defect but instead to cooperate. If you look at the payoff matrix below, the classic problem is that no matter what one player does (Cooperate or Defect), the optimal self-interested response is always to Defect. Before we get into strategies to elicit cooperation, we should start with the most obvious mechanism to evade the dilemma: to care about the outcome experienced by the other. Yes, strong pro-social preferences can eliminate the Prisoner’s Dilemma, but that is a big assumption amongst strangers. Among kin, however, it’s much easier. Family has always been the first and foremost solution. Parents don’t have a prisoner’s dilemma with their children. It doesn’t take a large leap of imagination to see how kin relationships would help familial groups coordinate hunting and foraging or il Cosa Nostra ensuring no one squeals to the cops.

Kinship remains the first solution, but it doesn’t scale. Blood relations dilute fast. I’m confident my brother won’t defect on me. My third-cousin twice removed? Not so much. The reality is that family can only take you so far. If you want to achieve cooperation at scale, if you want to achieve something like the wealth and grandeur of the modern world, you’re going to need strategies and institutions.

Strategies

There are many, if not countless, ways to support cooperation among non-kin. Rather than give an entire course in game theory, I’ll instead just enumerate a few core strategies.

- Tit-for-Tat = always copy your opponent’s previous strategy

- Grim Trigger = always cooperate until your opponent defects, then never cooperate again

- Walk Away = always cooperate, but migrate away from prior defectors to minimize future interaction

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is far, far easier to solve amongst players who can reasonably expect to interact again in the future. The logic underlying all of these strategies is commonly known as The Folk Theorem, which is the broad observation that all cooperation games are far easier to solve, with a multitude of cooperation solutions, if there is i) repeated interaction and ii) an indeterminate end point of future cooperation.

Strategies can facilitate cooperation with strangers, which means we can achieve far greater scale. But not as much as we observe in the modern world, with millions of people contributing to the survival of strangers over vast landscapes and across oceans. For that we’re going to need institutions.

Institutions

Leviathan is simply Thomas Hobbes’ framework for how government solves the Prisoner’s Dilemma. We concentrate power and authority within a singular institution that we happily allow to coerce us into cooperation on the understanding that our fellow citizens will be coerced into cooperating as well. That coercion can force cooperation at scales not previously achievable. It can build roads and raise armies. This scale of cooperation is the wellspring for both some of the greatest human achievements and our absolutely darkest and most heinous sins. Sometimes both at same time.

Governments can achieve tremendous scale, but there remain limits. My mental framing has always been that individual strategies scale linearly (4 people is twice as good as 2 people) and governments scale geometrically (i.e. an infantry’s power is always thrice its number). Geometric scaling is better, but governments always eventually run into the limits of their reach. Coercion becomes clumsy and sclerotic at scale. There’s a reason there has never been a global government, why empires collapse.

Markets can achieve scale unthinkable by governments because their reach is untethered to geography. Markets are networks. They scale exponentially. They solve the prisoner’s dilemma through repeated interaction and reputation. The information contained in prices supports search and discovery processes that both support forming new relationships while also creating sufficient uncertainty about future interactions. Cooperation is a dominant strategy. This scale of cooperation, of course, is not without critical limitations. Absent coercion there is no hope for uniformity or unanimity. No completeness. Public goods requiring uniform commitment or sacrifice are never possible within markets. The welfare of individuals outside of individual acts of cooperation (i.e. externalities) is not weighed in the balance.

There are other institutions that solve the prisoner’s dilemma. Religions, military units, sororities…the list goes forever. This article is already going to be too long, so I’ll start getting to the point. Much of the fundamental disagreement within politics and society at large is what comprises our preferred balance of institutions for supporting and maintaining cooperation, who we want to cooperate with, and the myths we want to tell ourselves about who we are or aren’t dependent on.

The Cooperative Corridor

Wealth depends on cooperation at scale. Wealth brings health and prosperity, but it also brings power. The “cooperation game” might be the common or important game, but it isn’t the only game being played. Wealth can be brought to bear by one individual on another to extract their resources. This is colloquially referred to as “being a jerk”. Perhaps more importantly, groups can bring their wealth to bear to extract the resources from another group. This is colloquially referred to as “warfare”.

Governments are an excellent mechanism for warfare. All due respect to the mercenary armies of history (Landsknechts, Condottieri, etc.), but markets are not well-suited to coordinate attack and defense. Which isn’t to say markets aren’t necessary inputs to warfare. This is, in fact, the rub: governments are good at coordinating resources in warfare, but markets are far better at generating those resources. A pure government society may defeat a pure market society in a war game, but a government-controlled society whose resources are produced via market-coordinated cooperation dominates any society dominated by a singular institution.

This all adds up to what I refer to as the Cooperative Corridor. A society of individuals needs to cooperate to grow and thrive. A culture of cooperation can be exploited, however, by both individuals who take advantage of cooperative members and aggressive (extractive) rival groups. Institutions and individual strategies have to converge on a solution that threads this needle. One answer might appear to be to simply cooperate with fellow in-group members while not cooperating with out-group individuals. This is no doubt the origin of so many bigotries—the belief that you can solve the paradox of cooperation by explicitly defining out-group individuals. Throw in the explicit purging of prior members who fail to cooperate, and you’ve got what might seem a viable cultural solution. The thing about bigotry, besides being morally repugnant, is that it doesn’t scale. The in-group will, by definition, always be smaller than the out-group. Bigotry is a trap. Your group will never benefit from the economies of scale as much as other groups that manage to foster cooperation between as many individuals as possible, including those outside the group.

As I noted in part II of my discussion of agent-based modeling, I published a paper a few years ago modeling how groups can thrive when they manage inculcate a culture of cosmopolitatan cooperation on an individual level, while supporting more aggressive (even extractive) collective insitutions. Cultures whose institutions and individual strategies exist within the corridor of cooperation will always be at an advantage. The point of the paper is decidedly not that we should aspire to being interpersonally cooperative and collectively extractive, but rather to demonstrate not just how cultures and institutions can, and often must, diverge. Institutions do not necessarily reflect an aggregation of the values or strategies held by individuals within a society. Quite to the contrary, selective forces in cultural evolution can push towards explicit divergence.

Pluribus

So what does this have to do with Pluribus?

[SPOILERS AHEAD if you haven’t watched through Episode 6]

You’ve been warned, so here’s the spoilers. An RNA code was received through space, spread across the human species, and now all but a handful of humans are part of a collective hive mind whose consciousnesses have been fully merged. That’s the basic part. The bit that is relevant to our discussion is the revelation that members of the hive mind 1) Can’t harm any other living creature. Literally. They cannot harvest crops, let alone eat meat. 2) They cannot be aggressive towards other creatures, cannot lie to them, cannot it seems even rival them for resources. 3) The human race is going to experience mass starvation as a result of this. Billions will die.

In other words, a cooperation strategy has emerged that spreads biologically at a scale it cannot support. It is also highly vulnerable to predation. If a rival species were to emerge in parallel, it would undermine, exploit, enslave, and eventually destroy it. The whole story borders on a parable of how a species like Homo sapiens could destroy and replace a rival like Homo neanderthalensis.

Cultural strategies are selected within corridors of success. Too independent, you die alone. Too cooperative, you die exploited. Too bigoted, you are overwhelmed by the wealth and power of more cosmopolitan rivals. Too cosmopolitan, you starve to death for failure to produce and consume resources. Don’t make the mistake of thinking the “corridor of success” is narrow or even remotely symmetric, though. On the “infinitely bigoted” to “infinitely cosmopolitan” parameter space, a society is likely to dominate it’s more bigoted rivals with almost any value less than “infinitely cosmopolitan.” So long as members of society are willing to harvest and consume legumes, you’re probably going to be fine (no, this isn’t a screed against vegetarianism, which is highly scalable. Veganism, conversely does have a much higher hurdle to get over…). So long as a group is willing to defend itself from violent expropriation by outsiders, they’re probably going to be fine. Only a sociopathic fool would see empathy as an inherent societal weakness. Empathy, in the long run, is how you win.

How this relates to political arguments

I almost wrote “current political arguments”, but I tend to think disagreements about institutions of cooperation are pretty much all of politics and comparative governance. We’re arguing about instititutions of in-group, out-group, and collective cooperation when we argue about the merits of property rights, regulation, immigration, trade, annexing territory, war. When we confront racism, nationalism, and bigotry, we we are fighting against forces that want to shrink the sphere of cooperation and leverage the resources of the collective to expropriate resources of those confined or exiled to the out-group. These are very old arguments.

The good news is that inclusiveness and cosmopolitanism are economically dominant. They will always produce more resources. But being economically and morally superior doesn’t mean they are necessarily going to prevail. The world is a complex and chaotic system. The pull towards entropy is unrelenting. And, in the case of cultural institutions and human cooperation, the purely entropic state is a Hobbesian jungle of independent and isolated familial tribes living short, brutish lives. Avoiding such outcomes requires active resistance.