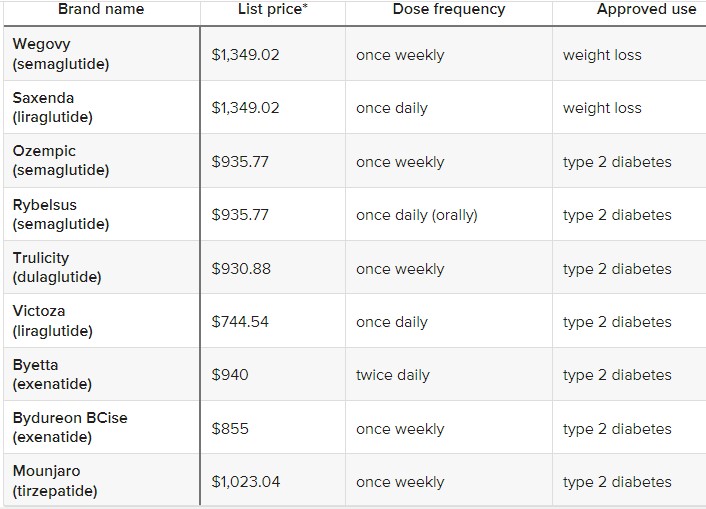

It seems like we finally have anti-obesity drugs that are effective and come without deal-breaking side effects: GLP-1 inhibitors like semaglutide (Wegovy). But they are currently priced over $10,000 per year for Americans. Should insurance cover them?

So far Medicare has decided to cover these drugs only to the extent that they treat diseases like diabetes (which these drugs were originally developed to treat) and heart disease (Wegovy reduces adverse cardiac events by 20% in overweight patients with heart disease). Just based on the diabetes coverage, Medicare was already spending $5 billion per year on these drugs in 2022, making semaglutide the 6th most expensive drug for Medicare with prescriptions still growing rapidly. The addition of other indications for specific diseases, like heart disease coverage added last month, is sure to expand this dramatically, especially if trials confirm other benefits.

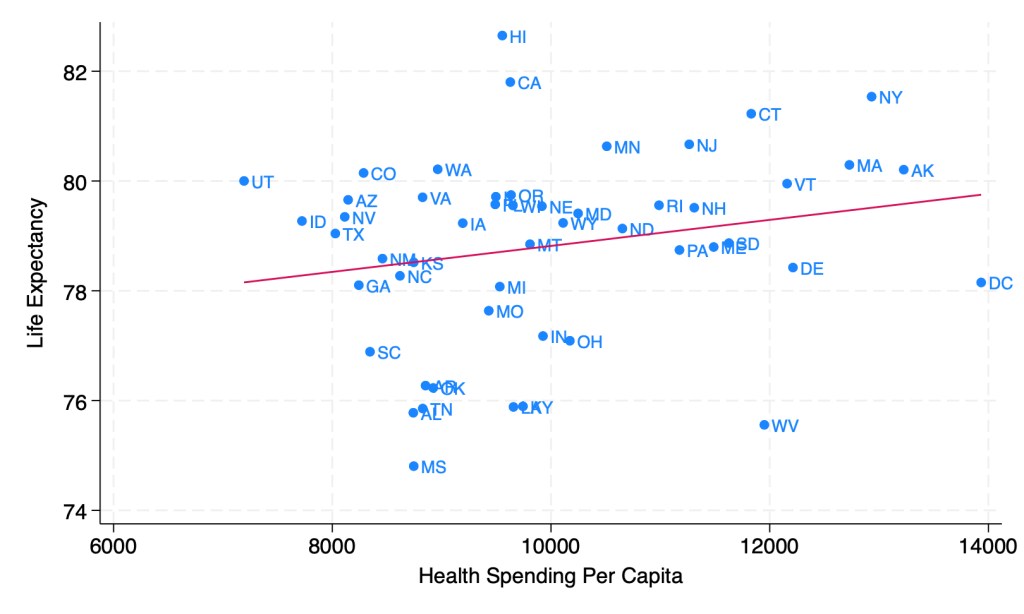

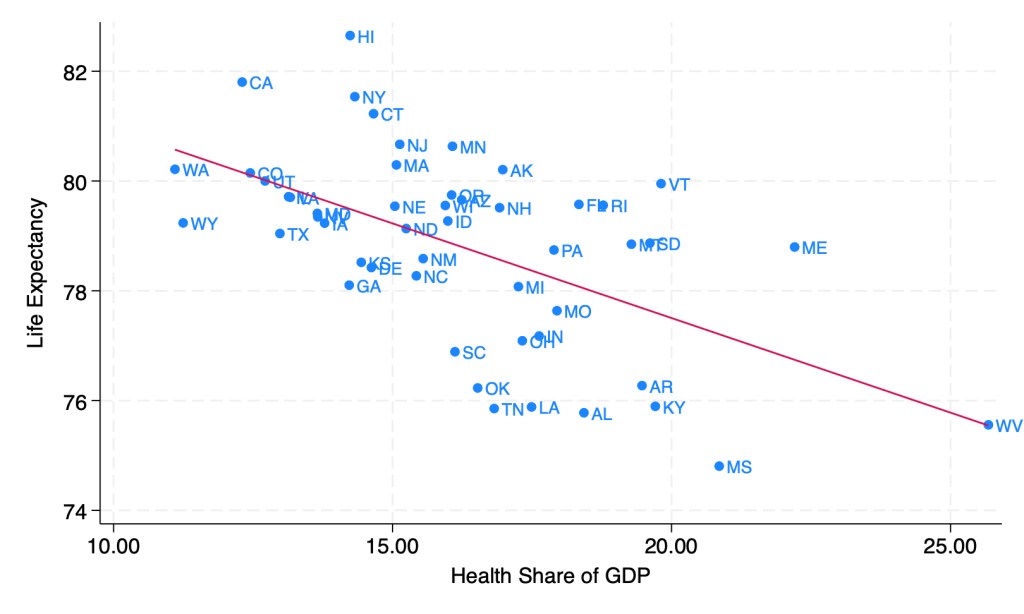

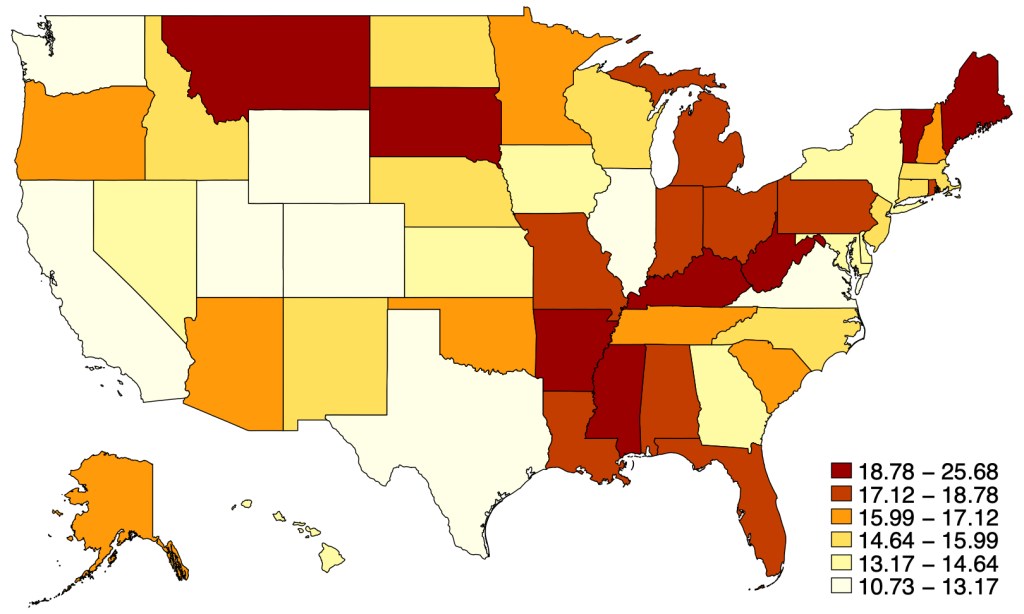

But with almost 3/4 of Americans now officially overweight, weight loss makes for a bigger potential market than any specific disease. Medicare currently spends about 15k per beneficiary for all medical care; if they actually paid for an 11k/yr drug for 3/4 of their beneficiaries, their spending could rise to 23k per beneficiary per year. The effect on Medicare Part D, which covers prescription drugs and currently spends about 2.5k per beneficiary per year, would be even more dramatic, with spending quadrupling. This would blow a huge hole in the federal budget, where health insurance already accounts for about 1/4 of all spending (and Medicare 1/2 of that 1/4).

Of course, the reality would not be nearly that bad. Not all overweight people would want to take a weight loss drug, even if it were covered by insurance; the side effects are real. To the extent people do take the drugs, the reduction in obesity could lead to lower spending on treatments for things like heart attacks. Rebates can already reduce the cost of these drugs to be less than half of their list price, and Medicare may be able to negotiate even lower prices starting in 2027. Key patents will expire by 2033, after which generic competition should dramatically lower prices. Competition from other brand-name GLP-1 drugs could lower prices much sooner.

Patents always come with a tradeoff: they encourage innovation in the future, but mean high prices and under-use of patented goods today. The government does have one option for how to lower the marginal price of a drug without discouraging future innovation: just buy out the patent. This would likely cost hundreds of billions of dollars up front, but this could be recouped over time through lower spending, while bringing large health benefits because the drug would be much more widely used if it were sold at a price near its marginal cost of production.

Of course, for now supply of these medications is the bigger problem than the cost. Even with the current high prices and insurers tending not to cover drugs of weight loss alone, demand exceeds supply and shortages abound. The manufacturers are trying to ramp up production quickly to meet the large and growing demand, but this takes time. Insurers like Medicare covering weight loss drugs wouldn’t actually mean more people get the drugs in the short run, it would simply change who gets to use them.

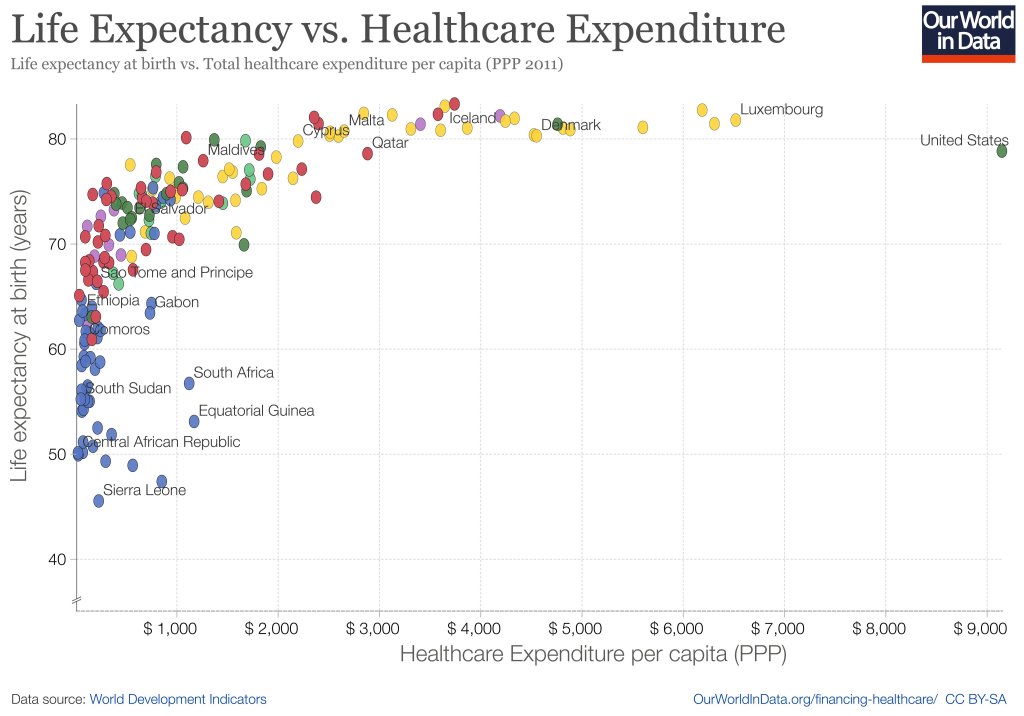

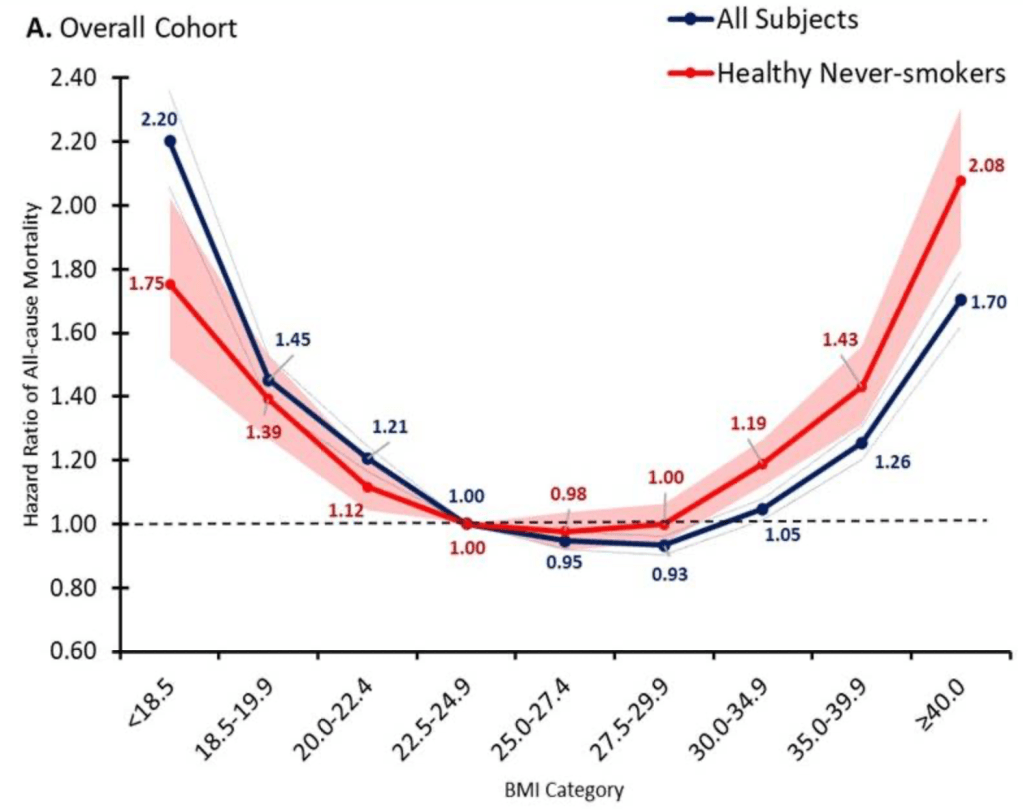

But once production ramps up, I do expect that it will make sense for Medicare to cover weight loss drugs. The health benefits appear to be so large that the drugs are cost effective even at current prices, and prices are likely to fall substantially over time. The big restriction I suspect will still make sense is to require that patients be obese, rather than merely overweight, since being “merely” overweight (BMI 25-29) probably isn’t that bad for you:

Disclosure: Long NVO

Update 4/18/24: I started thinking about this question because of an interview request from Janet Nguyen at Marketplace. She has now published an excellent article on the subject that also includes quotes from John Cawley of Cornell, who knows a lot more than I do on the subject.