This is the second of a series of occasional posts on observations of how some individual initiatives made strategic impacts on World War II operations and outcome. While there were innumerable acts of initiative and heroism that occurred during this conflict, I will focus on actions that shifted the entire capabilities of their side.

It’s the summer of 1941. The war in Europe between mainly Germany and Britain had been grinding on for around two years, with Hitler in control of nearly all of Europe. The Germans then attacked the Soviet Union, and quickly conquered enormous stretches of territory. It looked like the Nazis were winning. Relations with Japan, which aimed to take over the eastern Pacific region were uneasy. The Japanese had already conquered Korea and coastal China, and were eyeing the resource-rich lands of Southeast Asia and Indonesia. It was a tense time.

The Japanese military had been building up for decades, preparing for a war with the United States for control of the eastern Pacific. They developed cutting edge military hardware, including the world’s biggest battleships, superior torpedoes and a large, well-trained aircraft carrier force. They also produced a new fighter plane, dubbed the “Zero” by Western observers.

Intelligence reports started to trickle in that the Zero was incredibly agile: it could outrun and out-climb and out-turn anything the U.S. could put in the air, and it packed a wallop with twin machine cannons. Its designers achieved this performance with a modestly-powered engine by making the airframe supremely light.

As I understand it, the U.S. military establishment’s response to this intel was fairly anemic. It was such awful news, that seemingly they buried their heads in the sand and just hoped it wasn’t true. Why was this so disastrous? Well, since the days of the Red Baron in World War I, the way you shot down your opponent in a dogfight was to turn in a narrower circle than him, or climb faster and roll, to get behind him. Get him in your gunsights, burst of incendiary machine-gun bullets to ignite his gasoline fuel tanks, and down he goes. If the Zero really was that agile, then it could easily shoot down any U.S. plane with impunity. Even if you started to line up behind a Zero for a shot, he could execute a tight turning maneuver, and end up on your tail, every time. Ouch.

A U.S. Navy aviator named John Thatch from Pine Bluff, Arkansas did take these reports on the Zero seriously. He racked his brains, trying to figure out a way for the clunky American Wildcat fighters to take on the Zeros. He knew the American pilots were well-trained and were good shots, if only they could get some crucial four-second (?) windows of time to line up on the enemy planes.

So, he spent night after night that summer, using matchsticks on his kitchen table, trying to invent tactics that would neutralize the advantages of the Japanese fighters. He found that the standard three-plane section (one leader, two wingmen) was too clumsy for rapid maneuvering. He settled on having two sections of two planes each. The two sections would fly parallel, several hundred yards apart. If one section got attacked, the two sections would immediately make sharp turns towards each other, and cross paths. The planes of the non-attacked section could then take a head-on shot at the enemy plane(s) that were tailing the attacked section.

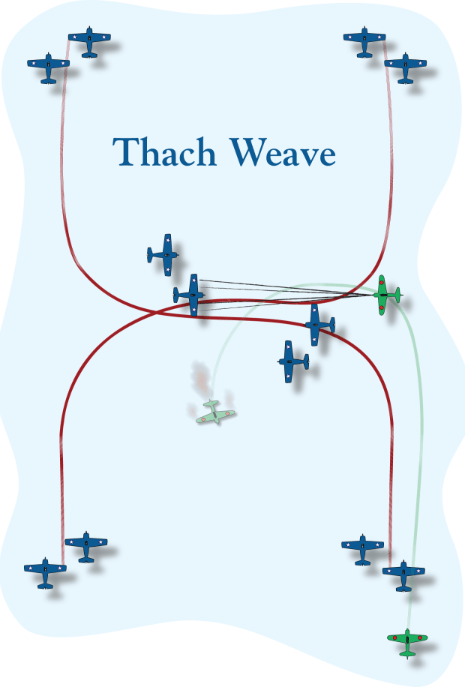

Here is a diagram of how this works:

Source: U. S. Naval Institute

The blue planes are the good guys, with a section on the left and on the right. At the bottom of the diagram, an enemy plane (green) gets on the tail of a blue plane on the right. The left and the right blue sections then make sudden 90 degree turns towards one another. The green plane follows his target around the turn, whereupon he is suddenly face-to-face with a plane from the other section, which (rat-a-tat-tat) shoots him down. In a head-to-head shootout, the Wildcat was likely to prevail, since it was more substantial than the flimsy Zero. Afterwards, the two sections continue flying parallel, ready to repeat the maneuver if attacked again. And of course, they don’t just fly along hoping to be attacked, they can make offensive runs at enemy planes as well, as a unified formation. This technique was later dubbed the “Thatch weave”.

Thatch faced opposition to his unorthodox tactics from the legendary inertia of the pre-war U.S. military establishment. Finally, he and his trained team submitted to a test: their four-plane formation went into mock combat against another four planes (all Wildcats), but his planes had their throttles restricted to maximum half power. Normally that would have made them toast, but in fact, with their weaving, they frustrated every attempt of the other planes to line up on them. This demonstration won over many of the actual pilots in the carrier air force, though the brass on the whole did not endorse it.

By some measures the most pivotal battle in the Pacific was the battle of Midway in June, 1942. The Japanese planned to wipe out the American carrier force by luring them into battle with a huge Japanese fleet assembled to invade the American-held island of Midway. If they had succeeded, WWII would have been much harder for the U.S. and its allies to win.

The way that battle unfolded, the U.S. carriers launched their torpedo planes well before their dive bombers. The Japanese probably feared the torpedo planes the most, and so they focused their Zeros on them. Effectively only Thatch and two other of his Wildcats were the only American fighter protection for the slow, poorly-armored torpedo bombers by the time they got to their targets. Using his weave maneuver for the first time in combat, he managed to shoot down three Zeros while not getting shot down himself. This vigorous, unexpectedly effective defense by a handful of Wildcats crucially helped to divert the Japanese fighters and kept them at low altitudes, just in time for the American dive bombers to arrive and attack unmolested from high altitude.

In the end, four Japanese fleet carriers were sunk by the dive-bombers at Midway, at a cost of one U.S. carrier. That victory helped the U.S. to hang on in the Pacific until its new carriers started arriving in 1943. Thatch’s tactic made a material difference in that battle, and was quickly promulgated throughout the rest of the U.S. carrier force. It was not a complete panacea, of course, since the once the enemy knew what you were about to do, they might be able to counter it. However, it did give U.S. fighters a crucial tool for confronting a more-agile opponent, at a critical time in the war. Thatch went on to train other pilots, and eventually became an admiral in the U.S. Navy.

Source: Wikipedia