In standard microeconomics, the long-run demand is unimportant for the market price of a good. Firm competition, entry, and exit causes economic profits to be zero and the price to be equal to firms’ identical minimum average cost. This unreasonably assumes that they have constant technology. That is, they have a constant mix of productive inputs and practices.

Just so we’re clear: time is passing such that firms can enter, exit, and adjust the price – but no productive innovation occurs. For the modeling, we freeze time for technology, but not for other variables. The model ceases to reflect reality on the margin of scale-induced innovation. The standard model assumes an optimal quantity of production for each firm and the only way for total output to change is for there to be more or fewer firms. The model precludes adopting any different technology because firms are already producing at the minimum average cost – if they could produce more cheaply, then they would.

Enter Scale

One of my favorite details about production was taught to me by Robin Hanson.* Namely, that the scale of production isn’t merely with the aid of more raw materials, labor, and capital. There are perfectly well-known existing technologies and methods that reduce the average cost – if the firm could produce a large enough quantity. This helps to illustrate what counts are technology. A firm can achieve lower average costs without inventing anything, and merely by adopting a superficially different production method.

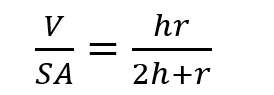

Here’s an example. Say that there is a foundry that produces steel. Part of that production process includes pouring molten metal from large cauldrons. For ease let’s assume that these cauldrons are the shape of an open cylinder.** If we double the diameter of the cauldron, then its external surface area increases quadratically. Specifically, the area of the base increases quadratically and the area of the wall increases linearly. If average cost of output is a function of the volume to surface area ratio, then that function simplifies to:

Note, that increasing the height of the cauldron increases the volume by a greater proportion than the surface area. Similarly, increasing the cauldron radius also increases the volume by more than the surface area. Therefore, merely by increasing the volume of output, a firm can reduce the average cost. Obviously, I don’t want to make too little of the innovation that goes into implementing such an idea. It may be that the cauldron material needs to change or the accoutrement surrounding it needs to change. But the fundamental idea is that no new invention is necessary – just application.

The implication is that long-run demand is a determinant of technology. This is a big deal conceptually. Macroeconomists typically consider demand when evaluating price level or short-run fluctuations. The long-run supply is determined by other factors. Once we let scale influence minimum average cost, we start to get different policy prescriptions. Suddenly, greater immigration and births become much more attractive by virtue of greater demand. Taxes don’t just cost us dead-weight loss, they also cost us innovation-stimulating scales of output. In fact, any policy that reduces the quantity of market transactions reduces our long-run standard of living doubly so: We lose the foregone consumption and we lose the innovation that the scale would have simulated. Increasing consumer demand in the long run increases simpler (?) innovation like increasing the scale of production. That’s relatively low hanging fruit compared to creating new inventions that have commercial application.

*I’m fairly certain that he said it explicitly, but I’m happy to give him credit either way.

**I’ve assumed no thickness to the cauldron walls. Adding thickness doesn’t change the conclusion.

Great post. My understanding is that subsidies/taxes don’t just change Q and P, but change the incentives firms face in choosing various technological or organizational arrangements to meet that Q long term.

Potential implications for the effect of subsidies and taxes to “speed up” and “slow down” technological adoption (and innovation).

LikeLike