A few weeks ago I wrote about several measures of the labor market, and whether the labor market was actually doing well. It’s a good idea to look beyond the headline unemployment rate, but even looking at alternative unemployment rates, labor force participation, employment rates, and unemployment insurance claims, I concluded in that post that the labor market is still looking healthy.

Lately I have heard another objection to the job growth numbers: part-time employment. I’ve seen this pop-up a few times on Twitter lately and just yesterday my co-blogger Scott Buchanan (in a post primarily about excess savings) stated that “much of the jobs creation this year has been in the part-time category.”

So is the jobs recovery mostly about part-time jobs? What is going on?

First things first: most of the data on part-time employment is from the household survey. There’s already a lot of noise in the household survey, due to the sample size, and part-time workers are a small share of the workforce, so expect it to be even noisier. In short, don’t trust one-month fluctuations too much. Furthermore, most of the data folks look at is seasonally adjusted. That’s generally good practice! But again, for a small number in a small sample, the seasonal adjustment factors won’t be perfect. Don’t read too much into one or a few months of data.

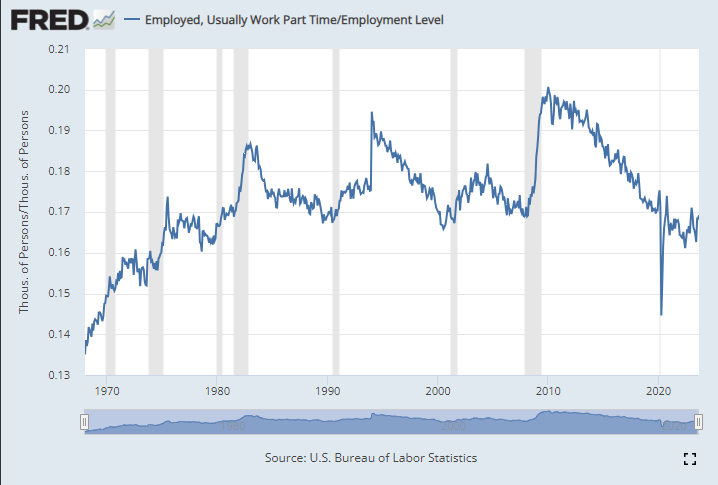

Let’s get the big picture first. How much of the labor force in the US is usually working part-time (defined in most data as less than 35 hours per week)? As usual FRED is the best place to go for graphing BLS data:

According to the latest monthly estimate, about 17 percent of workers in the US are part-time (technically 16.9 percent, but like I said, the data is a bit noisy, so let’s not get overly precise). Given the historical data, this actually looks like a very normal number. It’s lower than almost the entire period from 1980-2019, with the exception of the tail-end of long economic expansions.

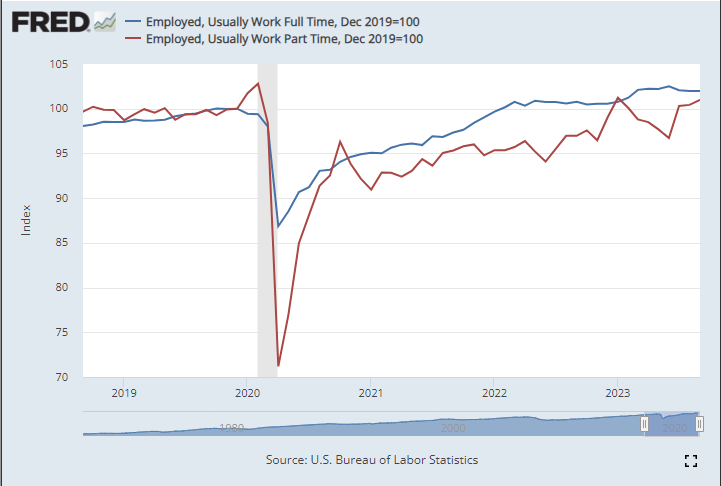

But it is a higher number than the past few years. Well, the main reason is that there were huge job losses among part-time workers during the early part of the pandemic. Once again, FRED is our friend:

Part-time employment took a massive hit in April 2020, dropping by almost 30 percent, more than double the drop in full-time employment. It bounced back quickly (but remember the usual caveats about this data month-to-month, especially during mid-2020 when data is really uncertain due to the pandemic), though it remained below the full-time recovery for the next 3 years. Full-time employment had recovered to December 2019 levels by February 2022, but other than a brief blip, part-time employment wasn’t consistently above December 2019 until 3 months ago (and note that if I anchor it in February 2020, part-time employment is still below the pre-pandemic level!).

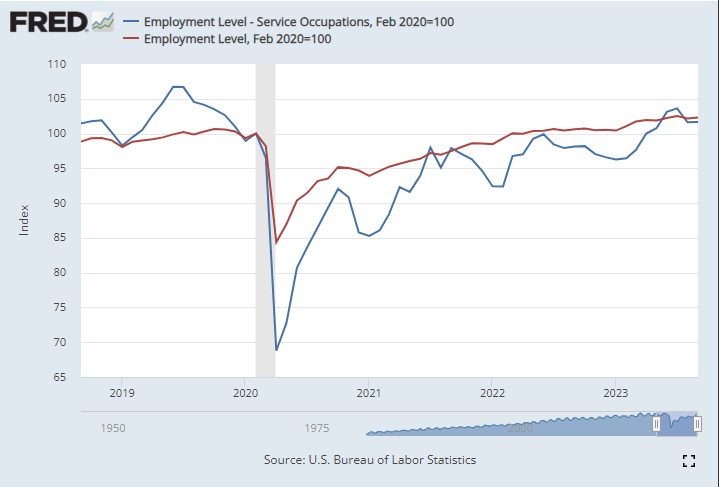

Why is this? Remember the early days of the pandemic and which types of workers were hit most acutely: service workers.

Employment in service occupations fell by over 30 percent in April 2020 compared with February, relative to 15 percent for all jobs (service jobs included!). As you will notice, this data is even more volatile, because for service occupations BLS only makes not seasonally adjusted numbers available (I also use the NSA total employment number in the above chart). There is a lot of seasonal fluctuation, but the recovery largely mirrors the full-time vs. part-time chart: overall employment recovered to pre-pandemic levels by March 2022, but service occupations took another year to fully recover. And there’s a reason that these two charts look similar: in 2019, service occupations were 28 percent of part-time employment (but only 14 percent of full-time employment).

Given all this, it is neither surprising nor worrying that much of the recent job growth has been part-time employment. And this part of the claims referenced earlier, such as of my co-blogger, are correct: much of the growth this year in employment has been part-time, about 22.5 percent since December 2022. That’s a lot more than we would expect in normal times. In fact, the “normal times” number isn’t really relevant, since part-time employment in absolute numbers is often very stable (for example, most of the decade prior to 2020).

Now that part-time and service occupation employment is back close to pre-pandemic levels, we would expect (and hope) that most the growth in jobs going forward won’t be in part-time occupations. We’ll have to wait and see. But the growth in part-time jobs is actually a great sign for most consumers, rather than a negative one. The one part of the economy that still seems to be lagging is in fact the service employment sector.

As consumers, we are mostly doing quite well (in spite of record inflation!), with one notable exception: service seems to suck. Restaurant service is slow. Fast food joints are often resorting to just drive thru service, and not because of health concerns — it’s labor shortages. Hotel service is slow or diminished. You are probably forced to use self-checkout at the grocery store more often. Etc. Employers are having a hard time hiring in this sector, and consumer are feeling the pain in the form of a new word we had to make up: skimpflation (shrinkflation has been long known and experienced).

The return of part-time employment might be exactly what this economy needs right now, rather than a bearish sign.

Nice data-digging, good explanation of why part-time employment has been increasing lately.

LikeLike