Some economists love to write about sports because they love sports. Others love to write about sports because the data are so good compared to most other facets of the economy. What other industry constantly releases film of workers doing their jobs, and compiles and shares exhaustive statistics about worker performance?

This lets us fill the pages of the Journal of Sports Economics with articles on players’ performance and pay, and articles evaluating strategies that sometimes influence how sports are played in turn. But coaches always struck me as harder to evaluate than players or strategies. With players, the eye test often succeeds.

To take an extreme example, suppose an average high-school athlete got thrown into a professional football or basketball game; a fan asked to evaluate them could probably figure out that they don’t belong there within minutes, or perhaps even just by glancing at them and seeing they are severely undersized. But what if an average high school coach were called up to coach at the professional level? How long would it take for a casual observer to realize they don’t belong? You might be able to observe them mismanaging games within a few weeks, but people criticize professional coaches for this all the time too; I think you couldn’t be sure until you see their record after a season or two. Even then it is much less certain than for a player- was their bad record due to their coaching, or were they just handed a bad roster to work with?

The sports economics literature seems to confirm my intuition that coaches are difficult to evaluate. This is especially true in football, where teams generally play fewer than 20 games in a season; a general rule of thumb in statistics is that you need at least 20 to 25 observations for statistical tests to start to work. This accords with general practice in the NFL, where it is considered poor form to fire a coach without giving him at least one full season. One recent article evaluating NFL coaches only tries to evaluate those with at least 3 seasons. If the article is to be believed, it wasn’t until 2020 that anyone published a statistical evaluation of NFL defensive coordinators, despite this being considered a vital position that is often paid over a million dollars a year:

While a few previous studies have focused on the role of head coaches in determining team performance, no previous study has considered the potential impact of defensive coordinators on NFL team performance.

Source: Pitts and Evans (2020)

Using 1970-2017 data and controlling for many team characteristics, they find that most coordinators don’t have any statistically significant effect on any major outcome, but a sizable minority do. They find that the best defensive coordinator (allowing 3 fewer points per game than expected) was Jim Bates, while the worst (allowing 5 points more than expected) was Bill Davis. Bill Belichick, despite his fame as a defensive coordinator and head coach, has no statistically significant effect; the head coach with the best reduction in points allowed is Ron Meyer (despite a 54-50 record in the NFL).

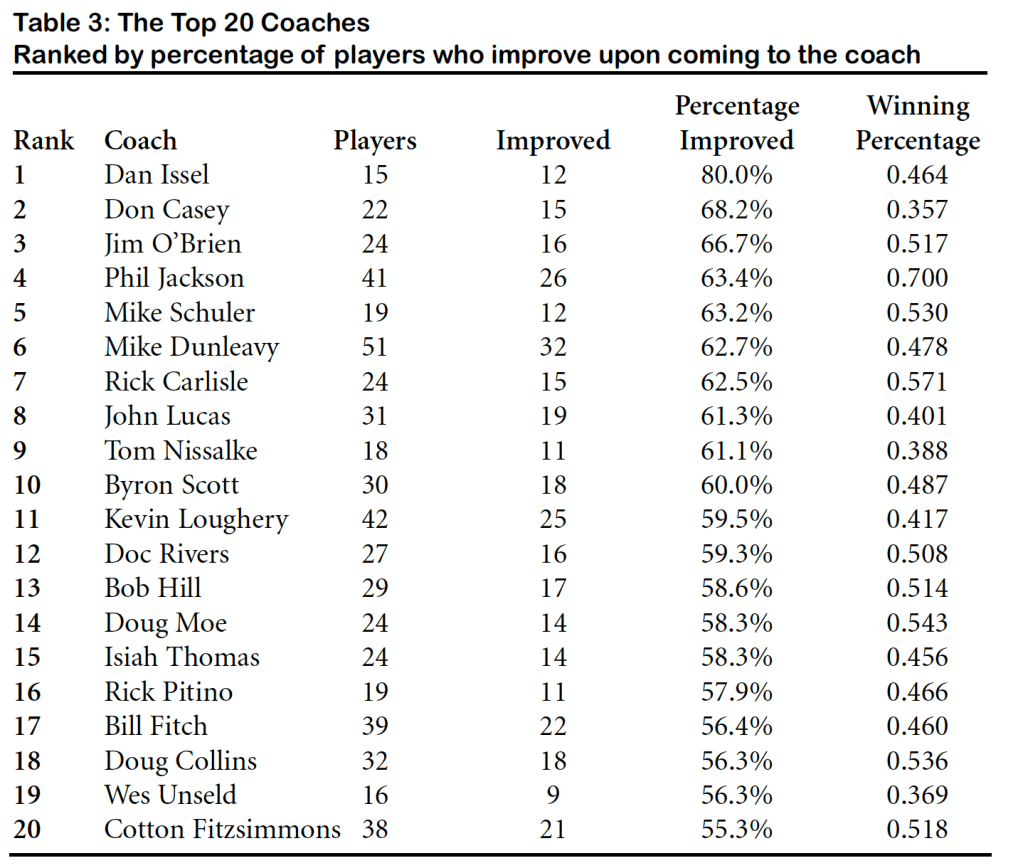

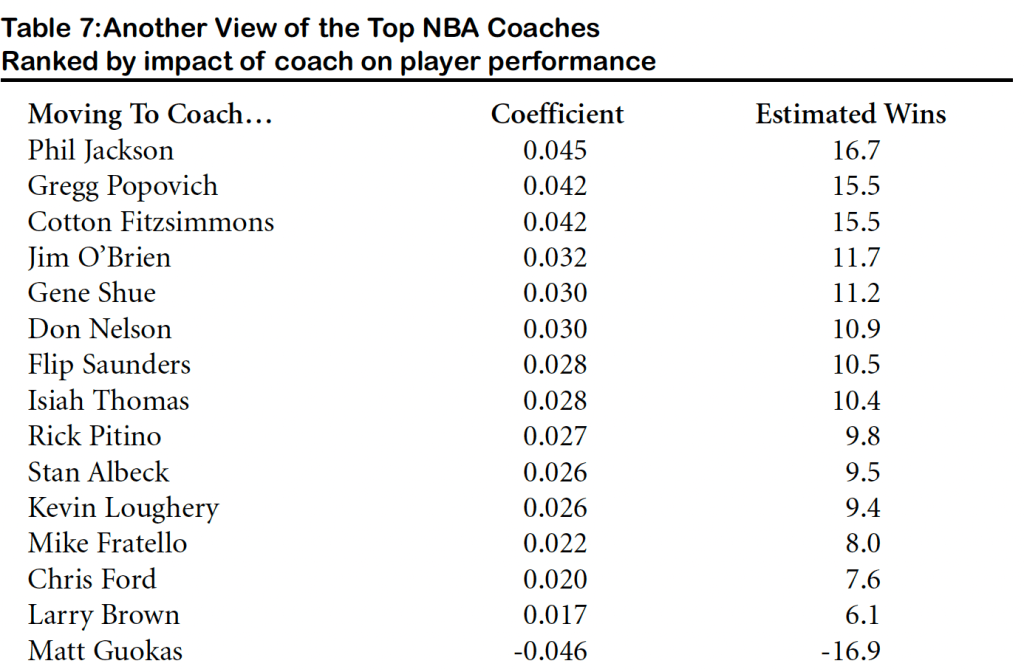

NBA coaches are a bit easier to analyze statistically since there are more games per season, but doing so produces similarly odd results. The legendary Phil Jackson looks good, but by many measures Dan Issel (who I hadn’t heard of before this, seems to be better known as a player than as a coach, and had a losing record as an NBA head coach) is the best. Jackson got to coach all-time greats Michael Jordan, Shaquille O’Neal, and Kobe Bryant; Issel did not (though Dikembe Mutombo was pretty good):

We find that some highly regarded coaches deserve their accolades, but several coaches owe their success to managing highly talented teams. Conversely, some coaches with mediocre records have made significant contributions to the performance of their players. Most coaches, however, do not have a statistically significant impact on their players or their teams, making them nothing more than the “principal clerks” that Adam Smith called managers over 200 years ago.

Source: Berry, Leeds, Leeds, and Mondello, (2009)

The Berry, Leeds, Leeds and Mondello paper uses a nice identification strategy of seeing how coaches affect players who join or leave their teams. But again, this means it take a while to evaluate a coach; the paper only considers coaches who had at least 15 players with substantial playing time join and leave their teams, leaving them with only 62 head coaches from the whole 1988-2008 period. The results are surprising:

Of course, like I keep saying, evaluating coaches well is tough; the paper considers several different ways to do it, some of which produce more traditional rankings:

All this in the sports world, with its plethora of data. Now imagine trying to evaluate managers in a regular company! In any one case you might be able to use lots of qualitative knowledge in addition to any data you have. But any individual case also has idiosyncrasies that make it impossible to know for sure. Consider legendary NFL coach (and economics major) Bill Belichick. With Tom Brady at quarterback, he won 6 Superbowls. Now into year 4 without Brady, he has a losing record. Does this mean he was always just an average coach who lucked into getting the greatest quarterback of all time? Or does it mean he used to be great, and is just getting old? Or just dealing with unusually bad players now? How is all of this changed by the fact that he is, unlike most coaches, effectively also a general manager who gets to pick his players? How should the Patriots think about when to fire him?

Even in sports, with some of the best data we have, there is still so much we don’t know. Sports analyst Bill James put it well on Econtalk:

the things that we don’t know outnumber the things that we do know. Not by 10% or 20%, but by ratio of billions to one. Consequently, when you remove a little bit of ignorance from the world, it doesn’t have any impact on the amount that remains, because of the ratio. Just last night, I was watching a football game; and there was a play in which a quarterback, Kirk Cousins, threw a flat pass that was tipped at the line of scrimmage and then intercepted. So, I went on Twitter, and asked my Twitter followers: What’s the data on this? Is throwing a flat pass, because it may be tipped at the line, is throwing a flat pass more likely to be intercepted than a pass that has some loft to it? And, the answer I got was: Nobody knows. It’s never been studied. There are millions of things like that: just, you know, that seem obvious. It’s an obvious question you’d think someone knows the answer. But nobody does.