There are two ways to increase profits or available funds: grow revenues or reduce costs. We typically laud the creative teams that identify paths to greater revenues while, at best, tolerating those in charge of tightening belts. Given the tones in which we speak of austerity, there’s the thought that perhaps those at it’s vanguard are underrated (and they probably are, at least relatively). On the other hand, we often find ourselves operating within an economy of credit and blame. Credit for revenue gains tends to spread to the whole team, while credit for profits attributable to spending cuts specifically accrue to the management imposing those cuts. In such a model, spending cuts would be overemphasized as a profit-maximizing strategy. Growth can also be overemphasized of course – venture capital has come to exist as an institution that seems to only be interested in “home run” investment outcomes, likely at the expense of simply supernormal returns. We could keep pursuing this line of thinking, but I’m not really interested in adjudicating where austerity or growth is overrated. I think there is a broader concern to be considered in the growth/austerity strategy dichotomy. Within such a model of optimal decision-making there is an unstated, but critical, assumption that the relevent set of revenues and costs is perfectly fungible, and in turn comparable, across all contexts.

I think of this phenomena as the Unified Theory of Excel (UTE), an operating principle that can take over decision-making within a company or institution. The UTE carries the false promise that all contexts across an operating entity can be reduced to columns in a spreadsheet and, in turn, a decision made by netting out the effect of changes to those columns. Now, If you think that I, your friendly neighborhood economist, am about to make woo-woo claims deriding the information held within costs and revenues, get used to disappointment. My concern lies in the arrogance, sometimes negligence, in the assumption that numerically identical changes in costs and revenues across different contexts are comparable. It’s not that the information within the columns is bogus or irrelevant, but rather that the lack for context characterizing the relationships between the columns undermines any hope for knowledge to be produced. Data are just meaningless numbers absent a model to characterize the relationships between the numbers. And that’s all a model is – an attempt to place the data in the appropriate context.

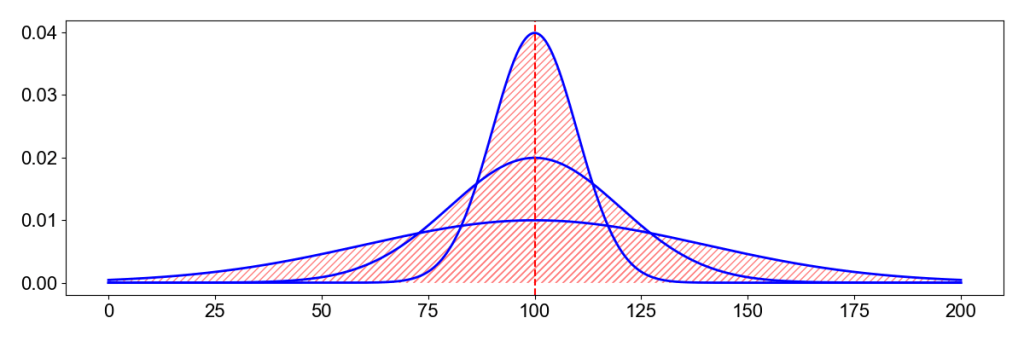

Complaints from those on ground about clueless management and soulless beancounters are, essentially, complaints that they are operating without a model. Cutting $100k from a marketing budget is not the same thing as cutting $100k on jet engine inspections and quality control. The world of possible outcomes from marketing cuts might include between $25k to $50k less in sales revenue, a large drop the worst attributable failure possible. In contrast, $100k quality control cuts will result in $100k in increased profits in 99% of possible outcomes, but of course there’s also a 1% chance that 10,000 people die in a fiery blaze, billions are lost in lawsuits, and the company ceases to exist. To be clear, I am fully aware of the resources that companies invest in projecting risk from decisions. Rather, the point is to illustrate the importance of context and the dangers of treating all numbers on a ledger as comparable and complete.

The Unified Theory of Excel is the belief that everything is fungible and can be abstracted to a spreadsheet absent any context or model. This belief in universal business fungibility is especially alluring given that the most recent wave of “people who got rich off of low-hanging fruit” were finance folks who observed the fungibility of risk across debt instruments. This false fungibility ignored the dangers of stripping numbers of context, which in the case of mortgage debt instruments included the relationship of ledgers across markets and higher statistical moments i.e. tail risk. Economic theory is built on abstraction, but abstraction has the fun property of being useful until it is disastrous. It’s the last step that kills you. Or creates a financial crisis. Or produces a jet where those 1% events keep happening.

What I am observing, in the news and broader conversation, is a frustration with management that I think is often being misinterpreted as “frustration with business” but I think is more correctly viewed as “frustration with business done poorly” or, perhaps more precisely, “business done with the wrong model”. Writers, actors, and film crews are frustrated with management operating with models that have been outdated for at least a decade. Journalists are losing their minds dealing with publishers who can’t keep outlets afloat and make payroll on time because an underlying model appears to be absent entirely. If this was purely about competing interests then the answer would, in theory, be available in competitive markets or at the collective bargaining table. But something seems off. It I didn’t know better, I’d be looking for a broad inefficiency, some sort of negative technology shock. An investment or commitment to operating in a contextual vacuum.

The thing about MBAs is they are generalists by training who often, by dint of their advanced credentialing, sometimes think of themselves as specialists. Their speciality being “business” carries with it an implied concept that business can be reduced to the universal application of their training and expertise, both of which have increasingly come to be…well…Excel. Excel is many things, but it is not a model (or at least not a very good one). Neither is “business”, for that matter. A spreadsheet supporting a pivot table embedded in a power point slide deck is something that you can carry from job to job, contract to contract. A 73kb hammer you carry in a world of nails waiting to be enumerated on your LinkedIn. It can accomplish tasks, present outcomes, but it offers no more context than a three-ring binder. It’s a model that says that everything is the same, everything is fungible. That the world can be reduced to mathematics no more complicated than 4th grade arithmetic. The sort of simple answer to a complex problem that HL Mencken warned us of.

One of my grad school classmates had a turn of phrase that I’ve grown to appreciate: “Hippy Hayekians”. These were folks who favored free markets not because business people were geniuses or heros, or because goverment was inherently evil, but because good decision-making comes down to the tacit knowledge that only comes from being in and of something, on the ground, embedded in it day to day. I’m by no means an Austrian economist, and my friend would never have put it this way, but I’m increasingly of the view that good management often does in fact come down to “vibes”. If, of course, by “good management” you mean a holistic understanding of the entire enterprise, including not just ledgers, but also risks, ambitions, culture, customers, and constraints. And by “vibes” you mean the tacit knowledge held and communicated by every single human being within a firm. Perhaps the occasional dog or cat.

I’m a data-driven guy down to my bones. Whether its criminal justice policy or how to produce a successful new brand of toothpaste, the best possible answer is in the data. But interpreting data is impossible without context, without a model. So maybe this whole post is a warning to be careful of anyone, be they managers, consultants, or management consultants, offering advice without a model.