Say that there is a labor market and that there is no income tax. If an income tax is introduced, then what should we expect to happen? Specifically, what will happen to employment, the size of the labor force, and the number of people unemployed? Will each rise? Fall? Remain unchanged? Change ambiguously? Take a moment and jot down a note to test yourself.

As it turns out, what your answer is depends on what your model of the labor market is. Graphically, they are all quantities of labor. The size of the labor force is the quantity of labor supplied contingent on some wage that workers receive. It’s the number of people who are willing to work. Employment is the quantity of laborers demanded by firms contingent on to wage that they pay. Finally, the quantity of people unemployed is the difference between the size of the labor force and the quantity of workers employed (Assuming that the labor force is greater than or equal to employment).

The standard perfectly competitive labor model is illustrated below left and with a tax below right. The nice thing about the perfectly competitive model is that the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity demanded if prices are flexible. Without a tax, employment and the labor force are identical where the marginal value of labor is equal to the marginal cost such that unemployment is zero. Adding a tax drives a wedge between the wage paid and the wage received. Employment falls along with the labor force and, nicely, unemployment remains zero. More realistically, there is frictional unemployment, but it’s independent of the tax and pricing of labor. So, if you think that income taxes reduce employment and worsen unemployment, then the perfectly competitive market is not your mental model.

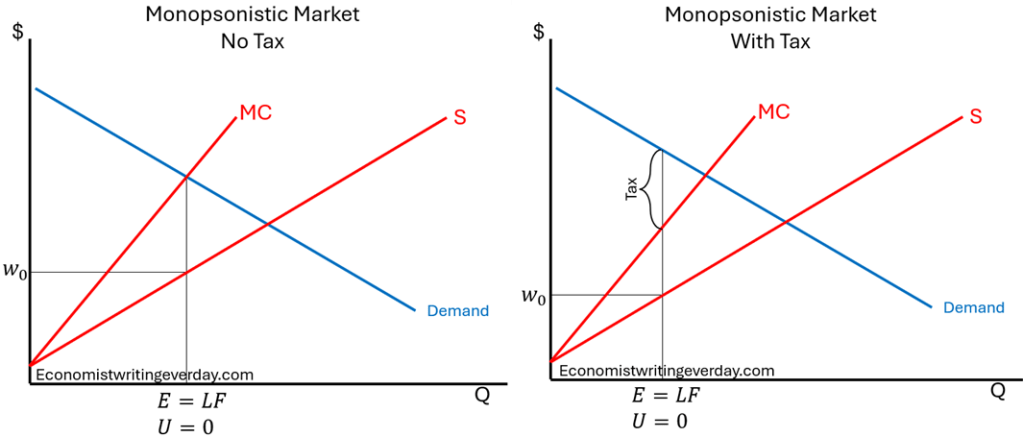

Another often-discussed labor market model is monopsony, which is the existence of only one employer and suppressed wages. This model is sensible if there are few or one demander for a type of labor. Without a tax (below left), the firm employs the quantity of labor at which the marginal cost of labor is equal to their marginal value. Again, employment and the labor force are identical and there is no unemployment. Adding a tax reduces both employment and the labor force identically, such that the changes in the labor market composition are identical to the perfectly competitive market. This overlap in model predictions is one reason that there is disagreement about what model characterizes US labor markets.

Awkwardly, however, the same labor market composition effects occur when there is a taxed monopoly. The labor force and employment decline and unemployment is unaffected.

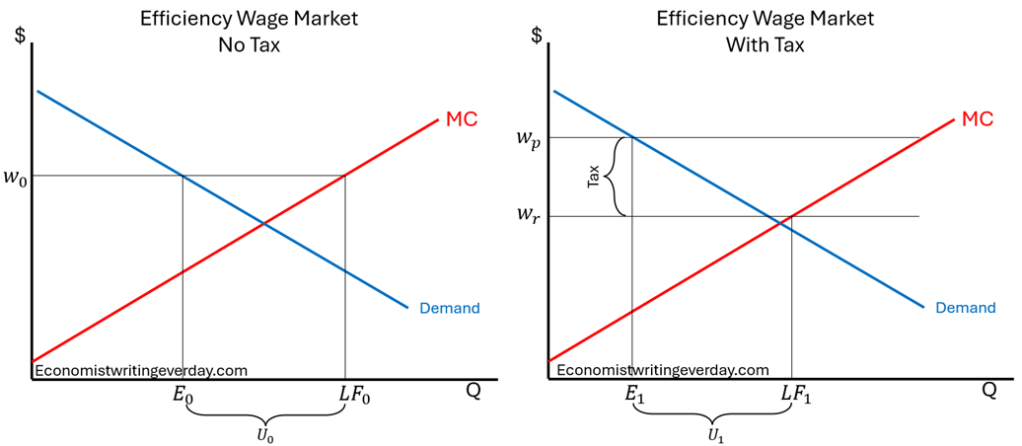

The final major model of employment markets is the Efficiency Wage model. In this model, firms reduce costly turnover by paying above the market clearing wage. The more costly turnover is, the higher the premium paid to keep workers. At the high wage, firms employ fewer people who are willing to work. This is the only major model here that includes unemployment. What’s the effect of a tax? Firms must pay some more in order to keep turnover down and laborers receive less. Therefore, both employment and the labor force decline. But what about unemployment?

The effect on unemployment depends on the relative slopes of the labor supply and the labor demand curves. It depends on the elasticities. In English, it depends on who has more alternatives. If workers have relatively more alternatives, then the labor force falls more than employment and unemployment falls. The flip side is that if firms have more alternatives to labor, then employment falls by more than the labor force and unemployment rises.

Look back at what you jotted down for your predicted labor market effects. All of the models agree that employment falls. Further, the perfectly competitive market, monopolistic market, and the monopsonistic market all predict a commensurate fall in the labor force such that the effect on unemployment is nil. The only model that predicts changes in unemployment due to a tax is the Efficiency Wage model.

If your initial predictions match your mental model for labor markets, then congratulations! You’re internally consistent on this topic. If there is a conflict between your knee-jerk reaction and the model that you believe describes labor markets, then it’s time to make some updates to your beliefs. If you think that taxes affect unemployment, then neither the monopsonistic nor the perfectly competitive markets describe your thinking. Further, if you think that the Efficiency Wage model is correct and that firms can be taxed with relatively little effect on their willingness to employ, then taxes reduce unemployment. Or, maybe you just made a mistake and you’ll change your knee-jerk love/hate relationship with taxes… regarding unemployment anyway.

EDIT: This is not to say that *nothing* affects unemployment in most models! Rather, just not taxes. Give me a paperwork requirement, and I’ll show you some regulation-induced frictional unemployment.

Unemployment is a pretty squishy metric: it’s value depends on whether people who are currently out of a job are answering surveys with “I’m still looking.” or with “Nope, I’ve given up.”

But the categories are full of gray areas.

A happy housewife, who doesn’t have a formal job but is also not counted as unemployed because she’s not looking, might still accept a really good job offer. And even someone who’s officially looking for a job (perhaps just so that they can claim unemployment benefits), might still reject most job offers.

LikeLike

Absolutely. You identify some important measurement problems. The theory side merely depends on people being 1) willing to work at the going wage and 2) being unable to find a job. So, your happy housewife would not be included in the theoretical ideal, nor would the picky benefit collector. There are even more measurement errors besides! Not to mention heterogeneous labor. But the theoretical models help us to relate the logic to reality if we could observe it.

LikeLike