The most interesting new paper in months dropped in last week: “Does Income Affect Health? Evidence from a Randomized Control Trial of a Guaranteed Income“

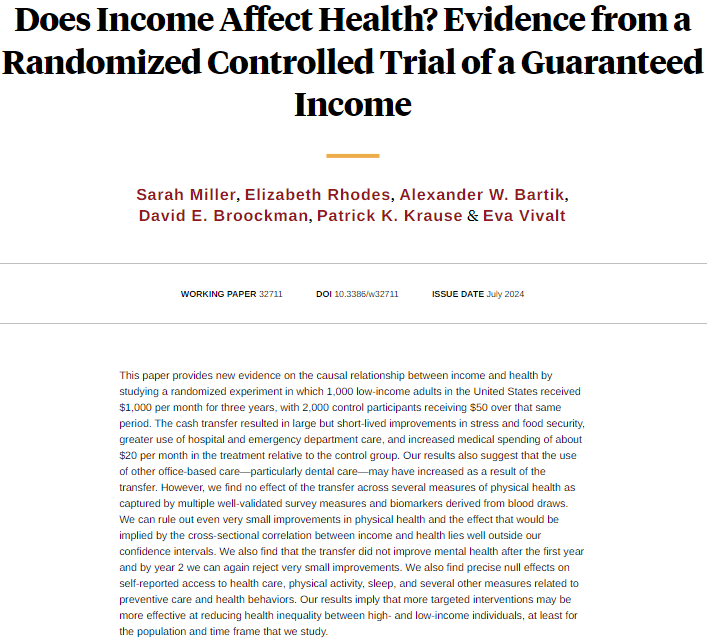

All the broad strokes are there in the abstract: $1000 per month, 2,000 participants (half treated), for three years. It’s the biggest, highest salience experimental test of a universal basic income program to date. There’s a lot of detail, but the broad strokes findings are that nothing happened. That is to say, there was a lot of precise null effects. And that is absolutely fascinating! I’ve gone back in forth on my feelings about a large scale UBI policy, and this is certainly more evidence that gives me pause, but my biggest takeaway is that policy research really should culimate in a series of field experiments whenever possible. Not because of identification or external validity or any of the other reasons economists fight in intellectual perpetuity, but because it’s easier to accept null results as sufficiently precise. It’s easier to acknowledge and accept that there is no observed effect because the treatment mechanism truly had no net effect within an experimental design.

Conducting research using observational data to produce causally identified conclusions is to fight a battle on multiple fronts. These fronts usually relate to the all the possible sources of bias, of endogeneity, within your analysis. You’re observing x causing y to increase, but the reality is that x is correlated with z, and that is what is actually causing y to increase. That’s a tough fight, believe me, as hypothetical sources of varying degrees of plausibility are hurled at your analysis from all directions. But at least there is an argument to be had. There’s something to fight against and over.

Null results face a far more insidious argument: there’s just too much noise in your analysis. Too many sources of variation, to much measurement error, too much something (that I don’t have to bother unpacking) and that’s why your standard errors are too big to identify the true underlying effect. There’s also a simple, and annoying, institutional reality: there’s no t-test for a precise zero. There’s no p value, so threshold for statistical significance that says this is a “true zero”. All we can say is that the results fail to reject the null. It’s subjective. And in a world of 2 percent acceptance rates at top journals, good luck getting through a review process where the validity of statistical interpretaton is assessed in a purely subjective manner.

Field experiments enjoy far more grace with null results. As random control trials, they can argue that their null effects are, in fact, causally estimated. If conducted within sufficient power (i.e. number of observations relative to feasible impact), then the results are simply the results. There’s no arguments to be had about instrumental variables, regression discontinuity cutoffs, or synthetic control designs. Measurement error will rarely be a problem given an appropriate design. External validity…well there’s no getting around external validity gripes, but should those concerns appear then the opposition has already accepted the statistical validity of your null results. You’ve already won.

I’m not puffing up my own team here, either. I’ve conducted several lab experiments, but never a field experiment. They are large, lengthy, and costly endeavors. I aspire to run a couple before my career runs its course, but I’ve built nothing on them to date. But they’ve grown in my estimation, even admidst concerns over participant gaming and external validity, precisely because you can run your experiment, observe no measurable impact on anything, and proclaim in earnest that that is precisely what happened. Nothing.

Precise null effects!

LikeLike