Economists are pretty united against tariffs. There are lots of complicated arguments. Keeping things simple, one reason is that they are bad for welfare. President-elect Trump seems to imply that tariffs can raise a lot of government revenue. But in lieu of what? The Tax Foundation estimates that there is absolutely no way that tariffs can replace all revenue from income taxes. The primary reason that they cite is that imports compose a tiny portion of the potential tax base. There are plenty of goods and services produced domestically that wouldn’t be subject to the tariffs. Any time we add a tax exemption, we’re adding complication, higher compliance costs, and distorting consumption patterns, etc.

For this post I singularly focus on the tax revenue. In fact, let’s demonstrate what *maximizing* tax revenue looks like under three cases: 1) Closed economy with a tax, 2) Open economy with a tax, & 3) Open economy with a tariff. I’ll use some simple math to demonstrate my point. None of the particulars affect the logic. You’ll reach the same general results with different intercepts, slopes, etc. Let’s start with a domestic demand and domestic supply.

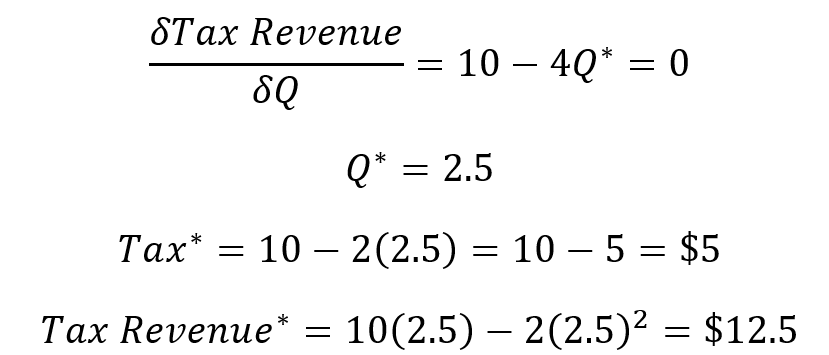

Closed Economy with a Tax

Whenever tax revenue is raised, there is a difference between the price paid by demanders and the price received by suppliers. In a closed economy a tax might be imposed on all goods. In these examples, I treat the tax as some dollar per-unit of output tax. But it’s a short jump to percent of spending taxes, and then another short jump to percent of income taxes. With this in mind, demanders pay more than the suppliers receive by the amount of the tax. Tax revenue is the tax rate times the number of units of output that are subject to the tax. That’s the thing we want to maximize.

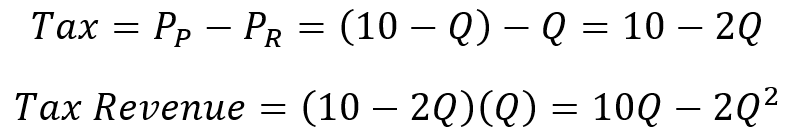

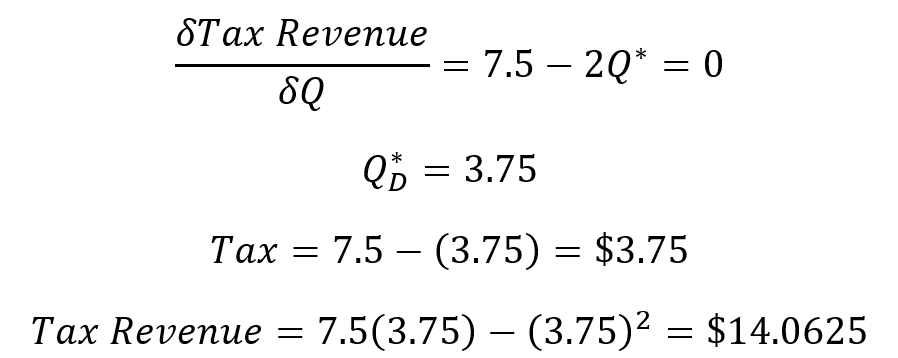

Conveniently, the tax revenue can be described by the quantity transacted, or the tax rate, or the price paid, or the price received. There are a variety of ways to tackle the problem. Regardless, the tax revenue-maximizing values are all consistent with one another. If we substitute the demand and supply equations into the tax equation, then we can express the tax rate in terms of the quantity transacted. Then, we can substitute that expression into the tax revenue function, making it a function of the quantity transacted.

Finally, a little bit of calculus lets us find the Q at which tax revenue is maximized. We can substitute that into the tax function and the tax revenue functions to find the tax revenue maximizing values.

That maximum tax revenue of $12.5 doesn’t mean much on its own. It’s simply derived from the other values. Rather, we care about how that number compares to the alternative means by which we can raise tax revenue.

Open Economy with a Tax

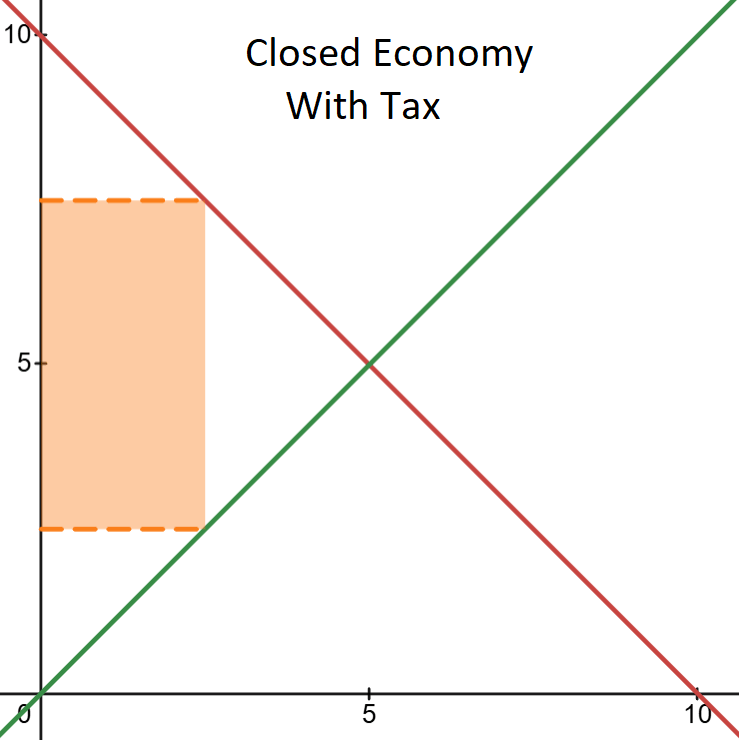

Let’s now open this economy up to international trade. We usually assume a constant world price for some good or basket of goods as a simplifying assumption. This assumption is perfectly fine for a small open economy. It may differ for economies that compose substantial portions of the world demand, but let’s stick with the simple case for now. I assume a world price of $2.5, this particular value doesn’t matter much. I chose it because it’s half of the domestic free market price. Obviously, changing the world price will change the maximum tax revenue. But it doesn’t change in a way that affects the quality of the logic.

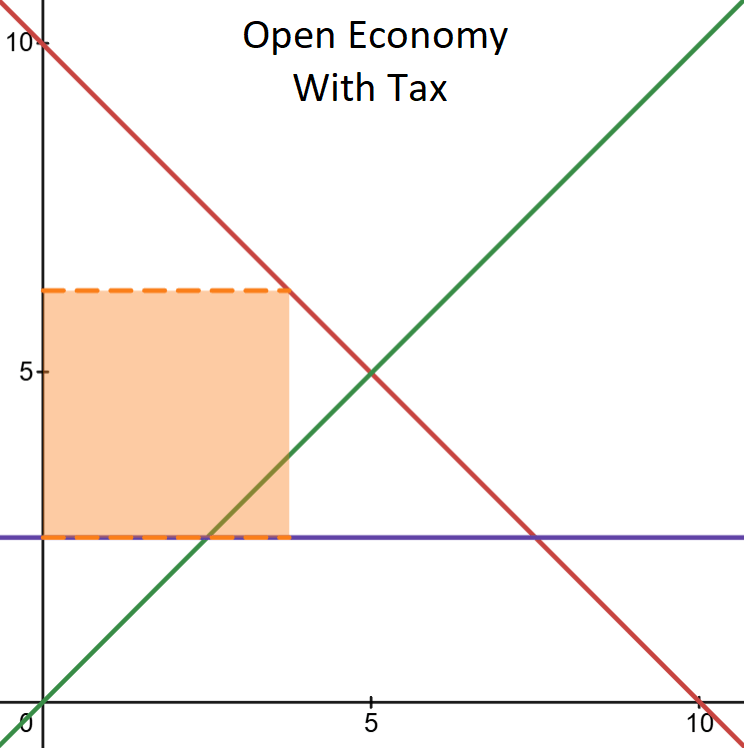

Once we have an open economy that faces a world price that is below the closed economy free market equilibrium, the economy begins to import goods. With a tax on all goods consumed, the origin of the goods, whether domestic or foreign, is unimportant. No one is exempt. The tax rate is the price paid by demanders less the world price. Just as in the closed economy case, domestic suppliers receive the price paid less the tax. The big analytical difference is that the quantity sold by domestic suppliers differs from the domestic quantity demanders by the quantity of imports. With imports, the quantity demanded is subject to the tax.

Again, we can substitute the demand equation into the tax and tax revenue equations and express them in terms of quantity demanded.

Calculus again can get us the tax revenue maximizing quantity demanded and the tax rate.

Wow, look at that! The maximum tax revenue that can be raised in an open economy is 17% larger. That number is a result that’s specific to the shapes of the demand and supply curves. But the fact that the maximum possible tax revenue is larger in an open economy is a general result.

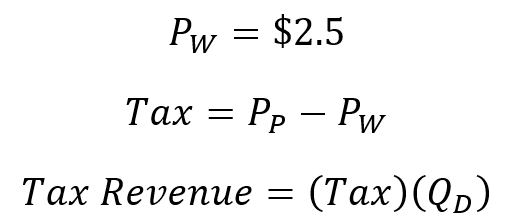

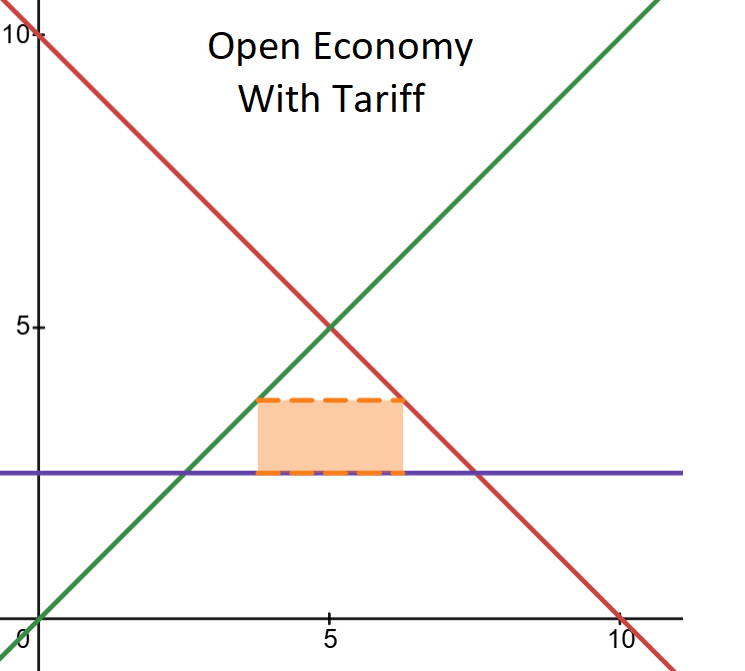

Open Economy with a Tariff

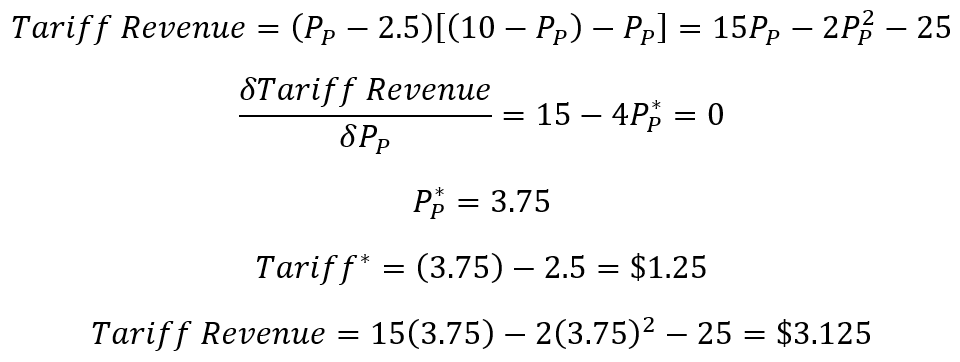

Finally, we examine the case of a tariff imposed on imported goods only, with no tax on domestically produced goods. The quantity of imports is the difference between the domestic quantity demanded and the domestic quantity supplied. A tariff is the difference between the world price and the price paid by demanders. But now, the domestic suppliers avoid the tax such that the price that they receive is the same as the price paid. All revenue is raised from imports.

Unlike the previous cases, I think that it’s easier to express tariff revenue as a function of the domestic price. I substitute the supply and demand functions into the tariff revenue function. Calculus gets us the tariff revenue-maximizing price paid.

My goodness! The maximum tariff revenue is miniscule compared to that yielded by the open economy with a tax. Indeed, that is a general result. The magnitude of the difference is up to the particulars. But the general results are driven by the fact that only a small part of the potential tax base is taxed: imports. Lowering the tariff shrinks revenue collected on each unit and increasing the tariff shrinks the quantity of imports that are subject to the tariff. The carveouts and exemptions reduce the maximum possible tax revenue. Importantly, all of this analysis doesn’t even touch on the welfare implications. If, for some reason, one wants to maximize government revenues, then tariffs aren’t going to do it. Indeed, if we raise the tariff rate highly enough, then we end up back at the closed economy. If the tariffs were supposed to replace the general tax, then no imports means no tax revenue.

If you tax land, or anything else with perfectly inelastic supply or demand, there’s no dead weight loss and the problem of maximising revenue looks very different.

LikeLike

absolutely! I prefer neither tax type in this post.

LikeLike