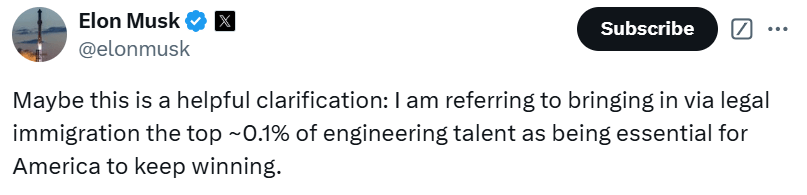

Several recent tweets(xeets) about tech talent re-ignited the conversation about native-born STEM workers and American policy. For the Very Online, Christmas 2024 was about the H-1B Elon tweets.

Elon Musk implies that “elite” engineering talent cannot be found among Americans. Do Americans need to import talent?

What would it take to home grow elite engineering talent? Some people interpreted this Vivek tweet to mean that American kids need to be shut away into cram schools.

The reason top tech companies often hire foreign-born & first-generation engineers over “native” Americans isn’t because of an innate American IQ deficit (a lazy & wrong explanation). A key part of it comes down to the c-word: culture. Tough questions demand tough answers & if we’re really serious about fixing the problem, we have to confront the TRUTH:

Our American culture has venerated mediocrity over excellence for way too long (at least since the 90s and likely longer). That doesn’t start in college, it starts YOUNG. A culture that celebrates the prom queen over the math olympiad champ, or the jock over the valedictorian, will not produce the best engineers.

– Vivek tweet on Dec. 26, 2024

My (Joy’s) opinion is that American culture could change on the margin to grow better talent (and specifically tech talent) resulting in a more competitive adult labor force. This need not come at the expense of all leisure. College students should spend 10 more hours a week studying, which would still leave time for socializing. Elementary school kids could spend 7 more hours a week reading and still have time for TV or sports.

I’ve said in several places that younger kids should read complex books before the age of 9 instead of placing a heavy focus on STEM skills. Narratives like The Hobbit are perfect for this. Short fables are great for younger kids.

The flip side of this, which creates the puzzle, is: Why does it feel difficult to get a job in tech? Why do we see headlines like “Laid-off techies face ‘sense of impending doom’ with job cuts at highest since dot-com crash” (2024)

Which is it? Is there a glut of engineering talent in America? Are young men who trained for tech frustrated that employers bring in foreign talent to undercut wages? Is there no talent here? Are H-1B’s a national security necessity to make up the deficit of quantity?

Previously, I wrote an experimental paper called “Willingness to be Paid: Who Trains for Tech Jobs?” to explore what might push college students toward computer programming. To the extent I found evidence that preferences matter, culture could indeed have some impact on the seemingly more impersonal forces of supply and demand.

For a more updated perspective, I asked two friends with domain-specific knowledge in American tech hiring for comments. I appreciate their rapid responses. My slowness, not theirs, explains this post coming out weeks after the discourse has moved on. Note that there are differences between the “engineers” whom Elon has in mind in the tweet below versus the broader software engineering world.

Software Engineer John Vandivier responds:

- I don’t take Elon’s comments to mean that elite labor is absent in America, but rather that marginal elite labor is absent. We have already saturated employment of those that are here and willing to be employed. Further, under some realpolitik calculus, America can and should win by fully hiring the entire world’s supply of elite labor.

- Vivek then offers another way of attaining elite engineering labor hours – take the elite talent we already have in the US and augment it with a culture that entices them to work more in a particular way on a per capita basis.

- I think you understand him well and your comments seem fine, in the direction of agreeing to an attenuated extent. This would make sense because his strategy simply doesn’t scale in the way that actual immigration form can, and it has all sorts of negative side effects at the extreme with respect to health, social concerns, and so on.

- I actually don’t think he makes a case for cultural reform at all. His case for cultural reform depends on our desire to make the world’s best engineers, but the tradeoffs may be severe. I think it is a fine response to Vivek to say “I don’t care if we produce the world’s best engineers,” and I wonder if this would be the popular response among my native-born peers. The popular issue with this response is the prevalence of anti-immigration bias. In my case, I’m happy to have a culture which depends on a steady supply of foreign engineers, but many Americans seem to want it all, an easy thing to want in a political system and a hard thing to achieve: Let’s have the world’s best engineers without making any changes to culture and restricting immigration. I’m reminded of all the typical variations in thought between economists and the typical voter.

- It is the case that the Software Engineering job post count has been significantly down in 2024 from peak, and in the laity’s eyes it looks like a predictable downward trend going forward.

- Employment is an emotionally charged subject and there is no shortage of particularly sad anecdotes. The narrative in the tech world has changed in a way that greatly overshoots the math.

- As a content creator, my posts advocating for a career in tech are routinely scoffed in Q4 of 2024.

- Obtaining and passing a technical interview is genuinely harder than it was at the peak of candidate-favoring conditions. A 30% decrease in the FRED job count index referenced about from 220 to about 150 from peak candidate’s market in Q1 of 2022 to the end of November in 2022 was associated with a 15% increase in difficulty of passing a Big Tech Software Engineer interview.

- As an engineer working at various companies, I have seen plenty of quality labor from both native-born and foreign sources. The employer-side concern typically seems to come down to pay, with natives typically asking for more pay. In some cases, this does mean that a native hire for the target skillset simply can’t be made given our financial and temporal constraints. There is a confounder here in that some employers still pursue diversity goals and may be willing to pay a premium for certain labor demography.

- As a technical career coach, I have seen many cases where individuals voice concerns and speculate a variety of causes about the reason they could not obtain an interview or they were not offered a role after obtaining an interview. Social media generally rewards emotional displays over dry discussions of market conditions, educational information, and serious conversation on optimal job search strategy. I genuinely can’t recall even one case where a qualified native-born individual was unable to eventually get a programming job. What I have seen includes:

- Longer individual job searches, which may be associated with some general increase in the unemployment rate. Even these can be avoided with proper job search technique. I was laid off personally in early 2024, but I was able to obtain a job offer within one month.

- Skill gaps in social networking, search techniques, and technical skills.

- Lack of interview preparation, which is particularly understandable when an individual was unexpectedly laid off.

- Lack of application volume, often by an entire order of magnitude.

- A suboptimal resume, LinkedIn profile, or portfolio.

- So, in this sixth item, there seems to be some modification of Vivek’s comments I can agree with: At the individual level, in many cases there is a native-born job candidate who feels things are hopeless but in fact they would get a job rather quickly if they significantly increased their efforts in a well-structured way. To that end, here are a few of my many articles for engineers on the job market:

There’s a relevant GMU article from this month on the topic:

https://business.gmu.edu/news/2024-12/least-one-leading-company-foreign-born-talents-are-paid-less

Software Engineer and manager Jeff Horn added more comments that I partly paraphrase here:

While elite companies like Elon Musk’s firms may genuinely need world-class talent, Horn says that most tech jobs are relatively mundane and don’t require exceptional abilities. The typical tech worker needs specialized knowledge but not genius-level capabilities – they must be competent enough to handle tasks that can’t be automated but aren’t expected to all be craftspeople.

The tech labor market has gone through distinct cycles, according to Horn. From 2015 to 2020, it was a seller’s market where engineers could frequently change jobs for significant raises of 20-50%. However, the post-2020 period has seen a market reversal with increased volatility, including the 2023’s market shake-up. Horn writes, “I recall in particular in 2023, voluntary leave also experienced a huge spike as the market shake-up fed the sellers’ and buyers’ hopes of being or finding top talent.”

“Fashion and trends are unreasonably dominant in tech. If the big companies are laying off… for most of us, the C-tier talent, these shake-ups mean months on unemployment while we send out (literally) thousands of applications and sit through hundreds of interviews…”

Jeff agrees that culture matters. Some Americans cannot even read well. There are few top computer programmers, but a culture that can’t produce lots of people with high reading comprehension has a problem. That’s why we can put schools, families, and/or the government on the list of possible roots of the problem.

Within tech companies, leadership quality varies dramatically, and meaningful career development and mentorship are rare. There’s a persistent communication gap between business and technical teams, with managers often resistant to technical feedback.

The characteristics of the tech workforce reflect these dynamics. Top performers tend to be single men working long hours, often treating coding as both their profession and hobby. Most workers, however, are “mediocre” – like any other field.

Jeff writes

We’ve got macro-level malinvestment into a chronically hype-driven tech sector and micro-level malinvestment into particular applications of technology. It’s a classic business cycle led by capital, with labor following. Some of each are left holding the bag once victory and loss have been realized, previously risky positions secured, and new infrastructure in place. I think a larger labor pool is a smart hedge against some of the risks; I suspect it makes assortative matching easier for firms having the means to search and to pay.

My attention was drawn this past week to how startup culture has been influenced by blitzkrieg tactics. I hadn’t previously appreciated the fact that blitzkrieg wasn’t just fast attacks, it was specifically fast attacks that ran ahead of its own supply lines as a calculated gamble to secure territory otherwise unsecurable with traditional strategies and timelines. It’s economically very costly in terms of lives, financial and technical capital. There’s also little doubt that it is very effective.

I’m not sure how much this adds to the conversation, but my mind has been focused on these dynamics at work rather than “no jobs” or “no workers”.

A topic Jeff brought up is something I noted in my literature review and policy paper The Slow Adjustment in Tech Labor: Why Do High-Paying Tech Jobs Go Unfilled? Tech labor is hard to hire and manage. In an ideal world, the HR staff and executives and managers would all have just as much technical knowledge as the workers themselves. Since that is not possible, inefficiencies and harms result. Sometimes talented tech people quit because the environment is so frustrating.

In Jeff’s words, “Tech is difficult to manage. How do they ever manage performance, let alone guide career development? It’s a fricking desert out here if you want meaning coaching and advancement, the only place most seem to find it is in latching on to an Obi-wan early on. I’ve had very mixed experience with tech leadership in my career. I’ve seen the kindest humans imaginable, and some of the worst tyrants.”

** End of comments from the software engineers **

Particularly having just shepherded children through a half-month of Christmas break from school, I am aware of the trade-offs we face on a culture level. My kids did some reading. Partly thanks to years of investment on my part, my son was able to consider a Calvin and Hobbes compendium to be his favorite Christmas gift, even above his first smartwatch on which Mom stubbornly refuses to load mindless video games. To the extent that I let them occasionally zone out on the TV, I was able to get some of my own goals accomplished (not to the point where I was able to get this blog post out in time to be the Current Thing).

Cultivating engineering excellence in our future workers or in ourselves as adults is costly because it comes at the expense of other things. Part of the reason that people are referring to “culture” is that culture determines values. The culture that values learning does not see achieving cognitive excellence as such a costly sacrifice.

However, no one seems to want a world where coders can only find jobs if they work 50+ hours a week and forgo having a family or outside hobbies. Indeed, it will be hard to find Americans to fill those types of jobs.

An economist who responded to Vivek right away (instead of weeks later like me) is Jeffrey Wooldridge:

So, to sum up the Elon/Vivek position: We should allow more immigrants to take entry/mid-level tech jobs that Americans want, but keep out immigrants who will do the jobs in agriculture, construction, and the service sector that Americans don’t want.

Wooldridge shares my moderate position on youth and education:

As a former scholar-athlete at my high school, I agree. But in my experience, a shift toward academics in the U.S. would be a good thing. Fortunately, my father, who was sports obsessed, insisted on high academic achievement. No sports without strong academics.

At this point, would I be remiss if I did not try the prompt “Are there no American tech workers, or a glut of workers and not many tech jobs?” at www.perplexity.ai/ ?

Perplexity begins with, “The current state of the American tech job market in 2025 is complex and somewhat contradictory. There is not a simple answer of either a shortage or a glut of tech workers, as the situation varies depending on specific skills, experience levels, and sectors within the tech industry.”

Ok. What sources does it use to answer the question? (Perplexity doesn’t hallucinate up fake sources.) Perplexity points me to what I might call heightened blogs. For example, you can try clicking on the link to a Business Insider article and run into the paywall. The most reputable source was the WSJ article: Tech Jobs Have Dried Up—and Aren’t Coming Back Soon

See my previous related post: Andrew Weaver is Searching for the Skills Gap

One thought on “No Tech Workers or No Tech Jobs?”