The US Equal Opportunity Commission identifies characteristics by which an employee can’t be harassed, hired, paid, or promoted. A challenge with enforcing the non-discriminatory standards is that the evidence must be a slam dunk. There needs to be a smoking gun of a paper trail, recorded conversation, or multiple witnesses. Mere statistical regularities are insufficient for demonstrating that characteristics like race, age, or sex are being considered inappropriately.

If employees are all identically qualified, then we’d expect the employment at a firm to reflect the characteristics of the applicant pool, within a margin of error due to randomness. One difficulty is that plenty of discrimination can occur within that margin of error. A firm may not have sexist policies, but a single manager can be sexist once or even multiple times and still keep the firm-level proportions within the margin of error. This is especially stark if the company managers or officers are the primary positions for which discrimination occurs.

Another difficulty is that randomness can cause extreme proportions of employee characteristics. Having a workplace that is 95% male when the applicant pool is 60% male isn’t necessarily discriminatory. In fact, given a sample size, we can calculate how likely such an employee distribution would occur by randomness. Even by randomness, extreme proportions will inevitably occur. As a result, lawsuits or complaints that have only statistical evidence of this sort don’t go very far and tend not to win big settlements.

But this doesn’t stop firms from avoiding the legal costs anyway. Firms generally prefer not to have regulatory authorities snooping around and investigating. Most people break some laws even unintentionally or innocuously, and a government official on the premises increases the expected compliance costs. Further, even if untrue accusations are made, legal costs can be substantial. Therefore, firms have an incentive to ensure that they can somehow demonstrate that they are not being discriminatory based on legally protected characteristics.

However, as I said, extreme proportions happen randomly. If those extremes are interpreted as evidence of illegal discrimination, then the firms have an incentive to hire among identical applicants in a non-random manner. They have an incentive to tilt the scales of who gets hired in favor of achieving a specific distribution of race, sex, etc. People have a variety of feelings about this. Some call it ‘reverse discrimination’ or discrimination against a group that has not historically experienced widespread disfavor. Others say that hiring intentionally on protected characteristics can help balance the negative effects of discrimination elsewhere. I’m not getting into that fight.

An Example

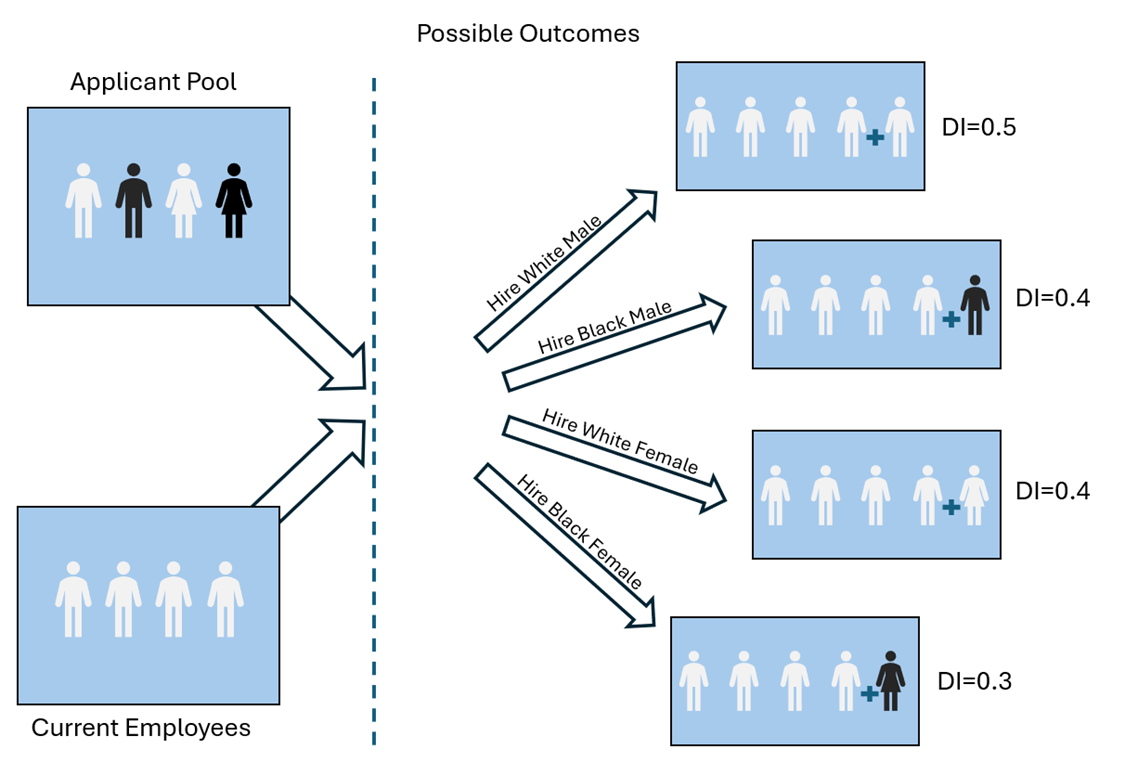

What I do want to emphasize is that the incentive for non-random hiring among identically qualified job candidates is entirely rational, given institutional constraints. Imagine a workplace with four white men. In the below example, I’ll focus only on their race and sex. They are seeking to hire a 5th person and their applicant pool includes four people: a white male, a black male, a white female, and a black female. Given the equal possibility of regulatory investigation or a lawsuit due to race and sex inequality and that all of the applicants are of equal ability, what should the firm try to do?

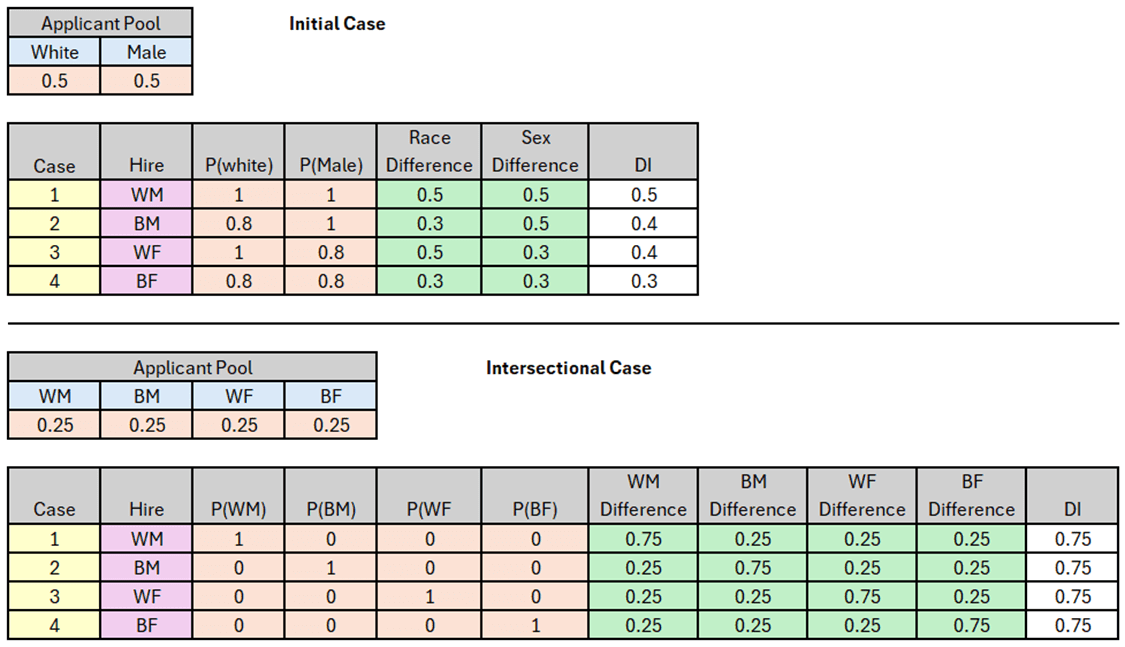

Their applicant pool is clearly half male and half white. If their risk exposure to legal costs increases with their deviation from this distribution, then what should they do? There are a variety of ways to measure the dissimilarity of two distributions. I’ll use a dissimilarity index (DI), which is the halved sum of absolute proportion deviations from the applicant pool. The bigger that number is, the more the employment characteristics differ from the applicant pool. Clearly, hiring a black female minimizes the risks of litigation for unfair hiring practices. This is because the firm can increase both underrepresented groups, females and blacks, by hiring one person. The firm has an incentive to hire non-randomly. The firm has an incentive to discriminate on the characteristics upon which they are prohibited from discriminating.

There are some caveats.

1) The logic is not one-way. If the initial employee pool was all black females, then hiring the white male would reduce legal risks most. Realistically however, white males tend to be in occupations that earn more than black females on average, meaning that we’re more likely to observe black females attempting to enter white male industries than the reverse.

2) Holding the entire employment pool to the standards of the pool of applicants to only one position is inappropriate. Prior hires were made under different circumstances and different applicant pools. Truly, the characteristics of that one hire, or set of hires, is the only appropriate comparison to make against the applicant pool.

3) Hiring the black female applicant only minimizes the dissimilarity index because of how we’ve described the employee characteristics of race and sex. We could have described race & sex with more categories without changing anything about the underlying details. We could have identified black females and black males as entirely different types of people. Indeed, intersectionality implies exactly that there are interaction effects among characteristics that are not merely the sum of the individual characteristic effects. This is why peoples say things like “as a black female” or “as a white male”. They are identifying their particular combination of race and gender effects.

If we repeat the example above taking caveats 2) & 3) into account, then any hiring decision will result in the same dissimilarity value no matter who is chosen. That’s because each person in the applicant pool is a unique race-sex group, differing in complementary ways from the other groups. Indeed, caveat 3) implies that the entire problem unravels as the we increase the number of groups characteristics. If each and every person can be uniquely described by their intersectionality, then there can’t be differences in measured dissimilarity between the applicant pool and the set of people that are hired.

See below where I show my work.

*Note: This analysis applies to the Dissimilarity index, but the principle at work is generalizable.