Two ideas coalesced to contribute to this post. First, for years in my Principles of Macroeconomics course I’ve taught that we no longer have mass starvation events due to A) Flexible prices & B) Access to international trade. Second, my thinking and taxonomy here has been refined by the work of Michael Munger on capitalism as a distinct concept from other pre-requisite social institutions.

Munger distinguishes between trade, markets, and capitalism. Trade could be barter or include other narrow sets of familiar trading partners, such as neighbors and bloodlines. Markets additionally include impersonal trade. That is, a set of norms and even legal institutions emerge concerning commercial transactions that permit dependably buying and selling with strangers. Finally, capitalism includes both of these prerequisites in addition to the ability to raise funds by selling partial stakes in firms – or shares.

This last feature’s importance is due to the fact that debt or bond financing can’t fund very large and innovative endeavors because the upside to lenders is too small. That is, bonds are best for capital intensive projects that have a dependable rates of return that, hopefully, exceed the cost of borrowing. Selling shares of ownership in a company lets a diverse set of smaller stakeholders enjoy the upside of a speculative project. Importantly, speculative projects are innovative. They’re not always successful, but they are innovative in a way that bond and debt financing can’t satisfy. Selling equity shares open untapped capital markets.

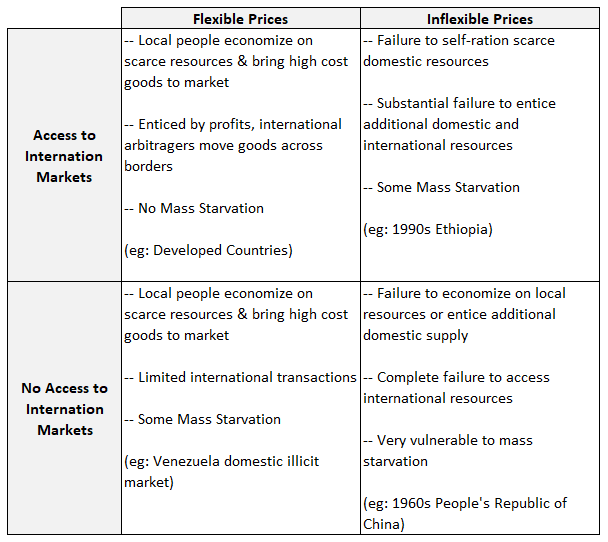

With this refined taxonomy, I can better specify that it’s not access to international trade that is necessary to consistently prevent mass starvation. It’s access to international markets. For clarity, below is a 2×2 matrix that identifies which features characterize the presence of either flexible prices or access to international markets.

What’s so special about flexible prices? In the context of a local famine or bad weather, flexible prices encourage consumers to ration their consumption and suppliers to bring more food to sell. How? Higher prices due to greater scarcity causes consumers to think twice about wasteful consumption because it’s expensive to do so relative to household budgets and relative to other non-food consumables. Similarly, higher prices entice suppliers to bring more to the market. Where does the additional food come from? From a variety of sources that don’t make sense at lower prices.

At lower prices, more scraps of wheat are left in the field because they cost too much labor to gather. Similarly, semi-wild berries or other foraging only makes sense for resale when prices are adequately high. Finally, stockpiling or hoarding goods is deterred since there is a very handsome reward for bringing those resources to market. The final result is that people in a country treat their suddenly scarcer resource as if it’s scarce, without a central authority, ineffective exhortation, or attempts at cooperation that require ‘good’ people. Flexible prices cause people to act as if they are ‘good’ – in the current context and on the described margins.

So, having flexible prices, even without access to international markets, can help mitigate the deaths that a famine might cause. But ultimately, people who stay in the food-scarce location may not have enough food. A bad enough famine can still cause mass starvation.

With access to international markets only, without the domestic institution of flexible domestic prices, starvation can still be mitigated and not entirely prevented. First, we lose all the deterrence to local hoarding, economizing on scarce food, and exploiting otherwise costly local options. In such a case, it’s possible that domestic demanders can access some of those internationally-sourced resources. But, if the domestic price is fixed and doesn’t reach as high as the international price, then there is little incentive for foreign suppliers to sell at a discount to the local population. So, local consumers can enjoy low prices without the benefit of the low-priced goods themselves. Low prices are little solace if you can’t purchase at those prices.

I don’t want to entirely discount political transactions that can send food to a famine-stricken area via barter or gifts. International trade can exist without international markets. Certainly, barter is possible, but it requires goods with low enough transaction costs and the coincidence of wants. It’s much more costly to get wool across an international border in lieu of money. Additionally, food-plentiful countries nearer to the equator may not value wool very highly. Political gifts are very messy and requires exchange of even less certain value.

Might Egypt garner political goodwill by sending food to Ethiopia in exchange for military support or a future favor? It’s possible. But the incentive faces those with political power or exceptional wealth. The typical person in Ethiopia or Egypt lacks the same ability and incentive to make such a transaction happen. The result is that foreign transactions *can* mitigate some starvation, but it can’t do it systematically in a way that is dependable across countries, religions, etc. Munger’s taxonomy contributes to this thinking by specifying that international trade is inadequate. International markets, which includes trade among strangers, is a necessary prerequisite to get resources to cross borders.

Finally, both flexible domestic prices and access to international markets can almost always avoid domestic mass starvations, categorically. A country that has both characteristics can do all of the typical rationing and enticing of domestic supplies. But it can also access foreign supplies in a very low-cost manner. Specifically, higher prices, which are a cheap and multi-lingual form of communication, attract foreign food by appealing to the relatively universal desire for some profits. Even foreigners who hate your guts can be persuaded to eagerly send helpful resources if they are adequately rewarded. This process doesn’t require political coordination or goodwill. Impersonal exchange in international markets gives everyone an arbitrage incentive to send valuable resources to places where they are scarce.

In summary, just as flexible prices and local markets can solicit more domestic resources and cause domestic consumers to self-ration, the added access to international markets causes global producers to respond generously to the higher global prices and global demanders to economize. Nobody needs to tell them how to do it. Flexible prices help every individual to act as if they care at all about someone else halfway across the globe. Mass starvation is still possible. A global event can make resources scarce everywhere. The social institutions described above are not magical. But globally flexible prices and impersonal exchange can mitigate a lot of suffering and despair. They help a great deal more than any other method of alleviating mass starvation that we’ve tried.