Tax holidays are when some set of goods are tax-free for a period of time. These might be back-to-school supplies for a week or a weekend, or hurricane supplies for several months. These policies tend to be popular among non-economists.

There are practical reasons for anyone to decry tax holidays. Usually, there is a particular type of good that qualify for tax-free status. These are often selected politically rather than by an informed and reasoned way with tradeoffs in mind. Sometimes, there is a subpopulation that is intended to benefit. However, the entire population gets the tax holiday and those with the most resources, who often have higher incomes, are best able to adjust their consumption allocations and enjoy the biggest benefits. A tax holiday weekend is no good to a single-mom who can’t get off work during that time.

Getting more economic logic, these holidays also concentrate shopping on the tax-free days, causing traffic and long lines that eat away at people’s valuable time – even if they aren’t purchasing the tax-free items. Furthermore, retailers must comply with the law. This means ensuring that all items are taxed correctly, making neither mistakes in over-taxing or under-taxing. Given the variety of goods and services out there, this is a large cost for individual firms.

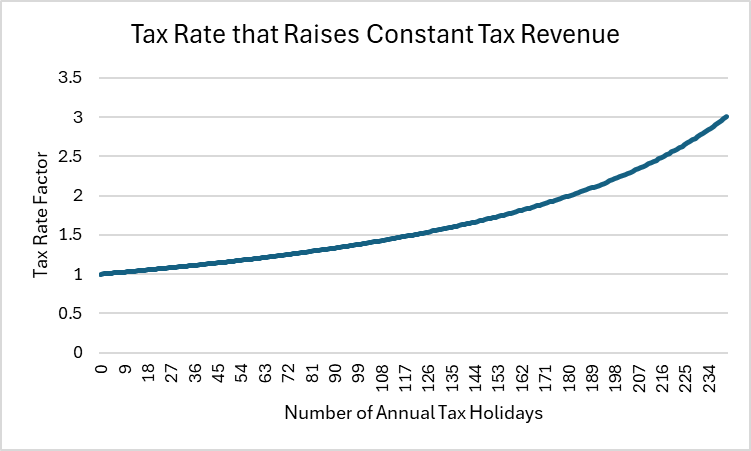

Finally, as economists know, there is a deadweight loss anytime that there is a tax. As a consequence, you might think that economists would love anytime that taxes are low. But, holding total tax revenue constant, a tax break on a tax holiday implies that there must be greater tax revenues on the other non-holidays. In particular, economists also know that losses in welfare increase quadratically with changes in tax rates. Therefore, higher tax rates on some days and lower rates on other days causes more welfare loss than if the tax rate had been uniform the entire time. In the current context, such welfare loss manifests as forgone beneficial transactions. These non-transactions are hard for non-economists to understand because we can’t see purchases that don’t happen, but would have happened in the absence of poor policy.

Let’s look at some graphs.

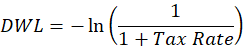

Given constant annual revenue, what’s the impact of a tax holiday on the otherwise standard sales tax rate? With the law of demand in hand* and no intertemporal substitution or avoidance, let’s see the relationship between the number of days of tax holiday and the amount by which the tax rate on the non-holidays must change. As the number of tax holidays increases, the tax rate on the remaining days must go up, and must increase more with each additional day of zero sales tax. The tax rate would be double in the presence of 179 tax holidays and triple if we have 239. That means a that rather than facing a 6% sales tax, one would face 12% and 18% respectively. I’ve truncated the graph x-axis because it peaks at day 357 at a factor of 424, after which one can’t collect the same revenue at any tax rate.

What about the consumer welfare? Because demand slopes down, the value placed on the greater consumption during a tax holiday is smaller than the value of the units forgone due to the higher taxes borne on the taxed days. This is why lost welfare increases fast as the tax rate rises. With each incrementally higher tax rate, each additional forgone unit of consumption is more valuable that the other forgone units. Below is a graph that shows the amount of welfare lost relative to the baseline of a uniform tax rate throughout the year. Again, I truncate the graph x-axis so that we can see greater detail. It tops out at 361 holidays reducing welfare by 2.6 times the loss of a uniformly applied tax throughout the year.

Both the welfare lost and the tax rate figures get really bad really fast if the taxed goods in question are goods for which demand is relatively elastic. That is, if goods have even partial substitutes, then the tax rate would need to be even higher in order to compensate for the small tax base. So, if legal pads are taxed and spiral-bound notebooks aren’t, then we’ll observe people buying more of the latter in lieu of the former.

Intertemporal substation also worsens both pictures. That is, if people know that the tax holiday will occur, then they will delay purchases in order to enjoy the lower tax rate and avoid purchases on the non-tax holidays. Again, this shrinks the tax base and increases the tax rate. Intertemporal substitution is easiest with durable (long-lived) and luxury goods (elastically demanded). The archetypal example in Florida would be permanent mechanical hurricane shutters. Every house has hurricane shudder panels that can be affixed manually. But some people opt to attach permanent fixtures to their house that can be more easily closed and opened. So, a substitute exists and there is no urgency for purchase. I’ll wait for the tax holiday, thank you very much.

Why don’t economists talk about the scourge of tax holidays more? Because on current margins, they’re not that bad. Yes, their distortionary, poorly targeted, and increase compliance costs. But, much like the minimum wage, economists have bigger fish to fry. Minimum wages affect a small part of the population and compose a small part of the cost of producing aggregate consumption. Rather than fighting the minimum wage, economists often like to focus on educational outcomes or business taxes that improve labor productivity. If the negative employment effects can be somewhat offset by improvements that would already be good policy on their own, then it makes little sense for economists to alienate others.

Similarly, sales tax holidays are relatively popular with the public and seem to have small negative welfare impacts relative to many other policies. So, if economists can get their win by broadening the sales tax base to some previously excluded goods, then that’s a win that makes fewer enemies. It’s not sensible to lose friends and influence by pursuing unpopular policies when more popular ones of similar value can be achieved.

*I assume a constant elasticity of -1. This makes the calculations easier, but it also satisfies Walras’ law (budget exhaustion). Changing the elasticity does affect the outcome, but the assumptions necessary to affect the quality of the outcome would be unrealistic. I also assume that the marginal cost of production is constant, such as in the long run perfectly competitive equilibrium.

Here are the consequent equations: