A periodically recurring conversation on social media is whether imports are bad for GDP. Everyone thinks they are clearly right, and then they lazily defer to brief dismissal of the opposing view. Some of this might be due to media format. Something just a tiny bit more thorough could help to resolve the painfully unproductive online interactions… And just maybe improve understanding.

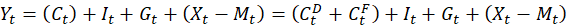

It starts with the GDP expenditure identity:

The initial assertion is that imports reduce GDP. After all, M enters the equation negatively. So, all else constant, an increase in M reduces Y. It’s plain and simple.

Many economists reply that the equation is an accounting identity and not a theory about how the world works and that the above logic is simply confusing these two things. This reply 1) allows its employers to feel smart, 2) doesn’t address the assertion, & 3) doesn’t resolve anything. In fact, this reply erects a wall of academic distinction that prevents a resolution. What a missed opportunity to perform the literal job of “public intellectual”.

How are Imports Bad/Good/Irrelevant for GDP?

Let’s add a small but important detail to the above equation to distinguish between consumption of goods produced domestically and those produced elsewhere.

Sticking with the identity, now we can better see where the imports happen (M) and where the imports are consumed (Cf).* It is definitely true that one more dollar of imports is subtracted from the rest of the equation. But, it is also true that those exact imports are consumed domestically such that the consumption of foreign-produced goods rises by an identical amount. So, the negative effect of the imports is exactly offset by the positive effect of the consumption.

Does this mean that the original claim that imports harm GDP is wrong? No! The fact that the equation is an identity sort of prevents us from making too many conclusions and instead just gives us the language to address the problem. We need to introduce some theory about how the world works in order to make more progress on the issue.

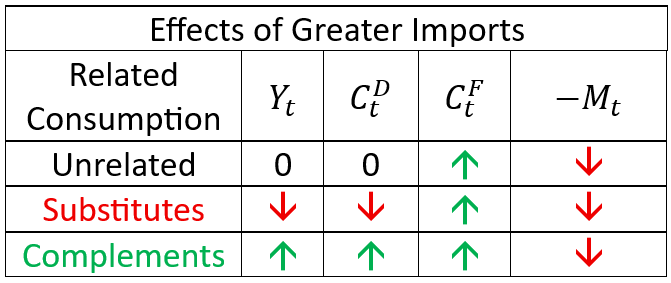

While it’s possible that the above case of ‘all else constant’ can occur in reality, there is no reason to presume that it’s true. Importantly, it may be that consumption of domestically produced goods is somehow related to consumption of foreign produced goods. In fact, it’s very reasonable that the relationship is non-zero.** There are three possibilities: 1) Consumption of domestic production is unaffected by consumption of imports. 2) Imports substitute consumption of domestic production. 3) Imports complement consumption of domestic production. The table below illustrates the 3 cases.

If consumption of foreign-produced goods and domestically produced goods are unrelated, then imports have no effect on GDP. This might be like importing durian or kangaroos. The people importing those goods wouldn’t necessarily have chosen a domestic alternative and may have saved their money instead.

The case that some people are afraid of is that imports replace domestic production. This might be like the early cases of Japanese cars replacing the domestic brands. For households with a single car, an imported car replaces a domestic car. If the imports depreciate more slowly, then it’s even worse than a 1-1 tradeoff! One Japanese car could substitute 2 less durable domestic-brand cars!

The less publicly emphasized case is the case of complements. It may be that imports and domestic production go hand-in-hand. Purchasing Japanese cars is an import of intellectual property that is bundled with domestic manufacturing. This is a case where both imports and domestic production rise. Another case might be Mexican avocados and domestic tortilla chips. Or Korean televisions and American sports entertainment. The imports increase the demand for related domestic products.

The social media conversations omit the application of clear theory to the GDP accounting equation.

In one sense, the argument is an empirical matter. An intrepid industrial policy maker might pursue the complementary imports and exclude the substitute imports. However, even here there are more microeconomic concerns with macroeconomic implications. Once we think about the economy as dynamically changing over time, we can ask what happens after we import substitutes for domestic goods.

Specialization across people and borders lets us engage in trade according to our comparative advantage. Freeing up some basic domestic manufacturing labor helps us to better afford more sophisticated manufacturing inputs. Or, since labor can be reallocated across industries, we can afford more medical professionals or software specialists. If these latter alternatives are more valuable than the ‘lost’ domestic manufacturing, then even the case of importing substitutes increases our GDP after an adjustment.

The bottom line is that a firm conclusion can’t be drawn from the GDP identity alone. Yes, imports can reduce GDP. And, yes, the GDP identity doesn’t tell us that it’s true.

*Of course, not all imports are consumption. Some are Investment or Government spending. So, we could decompose I and G into domestic and foreign sources too. However, it doesn’t change the logic of this post.

** We’re talking about the import elasticity of domestically produced consumption.