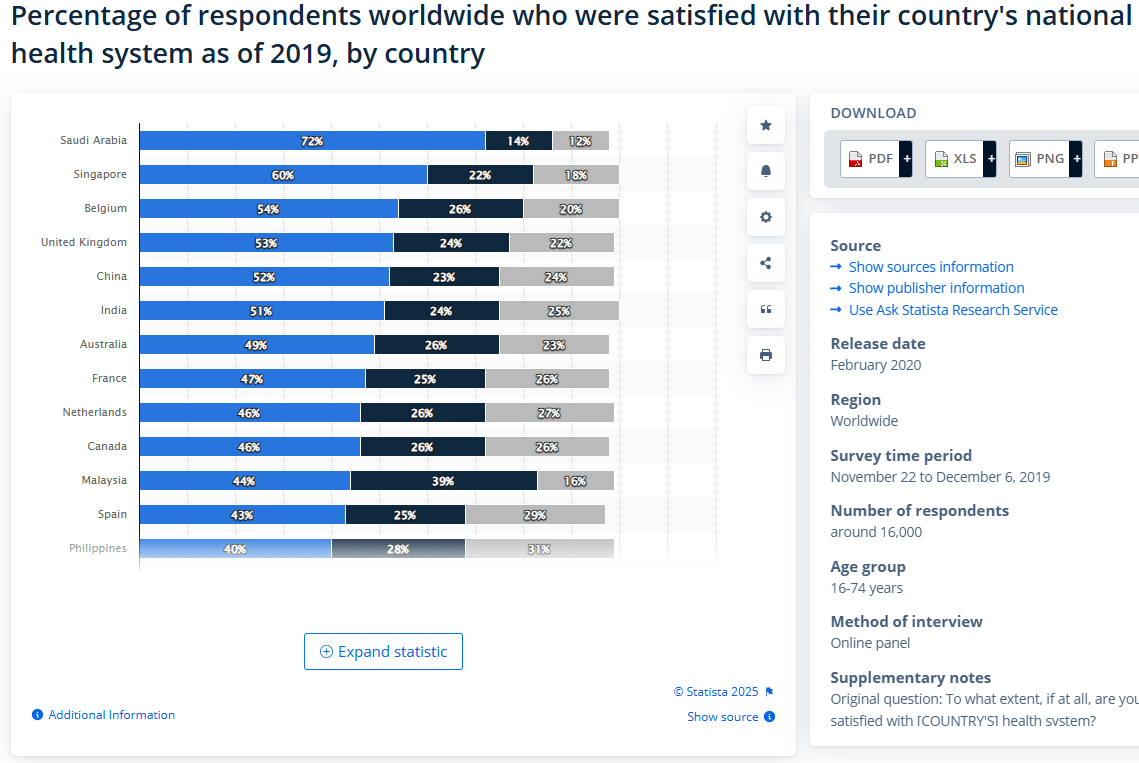

There is a broad consensus that healthcare in the United States is suboptimal. Why it is suboptimal is, of course, a subject of much debate, but that’s not what I am curious about at the moment. When people argue against the merits of the status quo, the superior systems of western Europe, Canada, the UK, and (occasionally) Singapore are mentioned. But if you look at most of those countries, the rate of satisfaction is, by the standards of most goods we consume, quite poor. In the survey reported below, 30% of US consumers are satisfied with their healthcare, compared to 46% of Canadians. The high water mark of “non-city states whose data I actually believe” is Belgium at a whopping 54%, and this is a survey conducted before the Covid-19 pandemic!

So while I have no doubt that improvements can be made in any system, there’s perhaps an under-discussed obstacle that may be unavoidable in any democracy: there is no stable political equilibrium because voters will never be happy with the status quo.

Here’s my simply reasoning.

- The wealthier we get, the more expensive healthcare will get. Healthcare is example 1A of Baumol’s curse in the modern world. No matter how much our economies grow, the cost of labor will grow commensurately, meaning healthcare will keep getting more expensive until we find a significant capital substitute for labor. (This is not a cue for AI optimists to chime in, but yes, I get it. We’ve been waiting for a “doc in a box” for a long time, and if the speed with which I got a Waymo is any indicator, we’ve got a ways to go before Docmo get’s real traction.)

- The wealthier we get, the more we value our lives. With that greater valuing comes greater risk aversion, and a greater willingness to pour resources into healthcare. If the labor supply of sufficiently talented and trained doctors can’t keep up, then wealth inequality is going to have a lot to say about how access to healthcare quality is distributed. Yes, there are positive spillovers as wealthiest individuals dump resources into healthcare, but are those spillovers enough to overcome envy?

- Citizens in wealthy countries are deep, deep into diminishing returns on healthcare expensitures. Combine that with growing risk aversion, and you’re got yourselves something of a resource trap, where you’re chasing a riskless, decision-perfect, healthcare experience that you can’t afford and likely doesn’t even exist.

- Fully socialized medicine a la the UK is of course an option, but the perils of connecting your entire healthcare system to the vicissitudes of politics is something being keenly felt since Brexit. Put bluntly, I always struggle with the idea of making healthcare wholly dependent on voters who will happily vote for anything so long as it doesn’t increase their taxes…

If economic growth allows for greater health, but that greater health itself pushes your baseline expectations for health farther out, then you’re on something akin to a hedonic treadmill— one where cost disease keeps increasing the incline. If the world getting better means that increased demand for healthcare will always outstrip increases in our ability to supply it, that it will always be too expensive and overly distributed to those wealthier than us, and if and when we do socialize healthcare voter demands will, again, outstrip their willingness to be taxed for it…I don’t see a clear path to satisfied consumers.

Maybe this is just me projecting, but I don’t have a hard time imagining that I’d be complaining about the quality of health care I’m receiving no matter what country I lived in, though I’d be willing to try out “Billionare in Singapore” if anyone wants to support a one household experiment.

If you look at this paper comparing the US to Norway, what happens at the top of the income distribution is interesting. Even among those who possess the top 20% of household wealth, there is a gap between the two countries. Wealth is necessary, but not sufficient. Culture matters, and as you state above, there are diminishing returns (flat of the curve) in terms of what we can buy in added years. But looking at us vs them, we can see Baumol is less of a curse in other places.

Association of Household Income With Life Expectancy and Cause-Specific Mortality in Norway, 2005-2015 | Cancer Epidemiology | JAMA | JAMA Network

LikeLiked by 1 person