I think there’s a lot of crosstalk about AI in part because proponents tend to focus on the immenient supply side shifts from innnovation, while critics seem to happily observe failures to stoke consumer demand. Not being much of a futurist, I’m largely content to watch and wait with minimal speculation. At the same time, I see signs of increasing demand for other products, in blatant disregard for past and present identity politics. It’s probably good to remember that supply and demand are less a beast to be wrangled than a rocking ocean to be adapted to.

Author: mdmakowsky

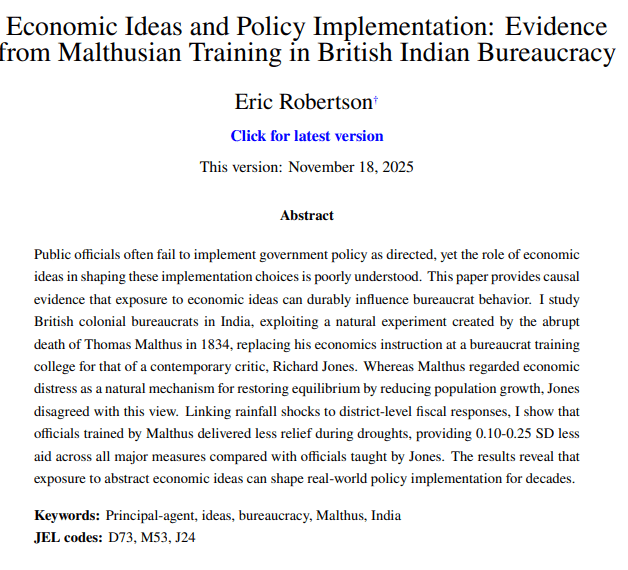

Bad ideas are costly

I know this has gotten coverage at other econ blogs, but I’ve been thinking about this paper for a couple days now.

Combine this with the classic Besley and Burgess paper on the political economy of government responsiveness to natural disasters, and you have a perfect Venn diagram of how bad ideas and bad political incentive alignment can lead to truly awful outcomes. An unfortunately “evergreen” mechanism in political economy.

Markets adjust: Superbowl quarterback edition

Yesterday’s super bowl was fun for a variety of reasons, but your 147th favorite economist was especially happy to see that markets continue to keep things interesting. The NFL was a “only teams with elite quarterbacks can win” league…until it wasn’t. After Brady, Manning, Brees, and Maholmes winning two decades of Super Bowls, we have back to back years of decidedly average quarterbacks winning (within-NFL average, to be clear. These are all objectively incredible athletes). How did this happen? Is it tactical evolution, flattening talent pools, institutional constraints, or markets updating? The answer is, of course, all of the above, but updating markets is the mechanistic straw that stirs the drink.

The NFL is a salary capped, which means each team can only spend so much money on total player salaries. As teams placed greater and greater value on quarterbacks, a larger share of their of their salary pool was dedicated accordingly. These markets are effectively auctions, which means eventually the winner’s curse kicks in, with the winner of the player auction being whoever overvalues the player the most. Iterate for enough seasons, and you eventually arrive at a point where the very best quarterbacks are cursed with their own contracts, condemned to work with ever decreasing quality teammates. Combine that with a little market and tactical awareness, and smart teams will start building their teams and tactics around the players and positions that market undervalues. And that (combined with rookie salary constraints), is how you arrive at a Super Bowl with the 18th and 28th salary ranked quarterbacks.

Whenever a market identifies an undervalued asset (i.e. quarterbacks 25 years ago) there will, overtime, be an update. Within that market updating, however, is a collective learning-as-imitation that eventually results in some amount of overshooting via the winners curse. This overshoot, of course, may only last seconds, as market pressure pushes towards equilibrium. In markets like long term sports contracts or 12 year aged whiskey, that overshoot can be considerable, as mistakes are calcified by contracts and high fixed cost capital.

What does this predict? In a market like NFL labor, I’d expect a cycle over time in the distribution of salaries, iterating between skewed top-heavy “star” rosters and depth-oriented evenly distributed rosters. At some point a high value position or subset of stars are identified and distproportionately committed to, but the success of those rosters eventually leads to over-committment, so much so that the advantage tilts towards teams that spread their resources wider across a larger number of players undervalued teams whose fixed pie of resources are overcommitted to a small number of players. That’s how you get the 2025 Eagles and 2026 Seahawks as super bowl champions.

I wonder when it will cycle back and what the currently undervalued position will be?

Unweighted Bayesians get Eaten By Wolves

A village charges a boy with watching the flock and raising the alarm if wolves show up. The boy decides to have a little fun and shout out false alarms, much to the chagrin of the villagers. Then an actual wolf shows up, the boy shouts his warning, but the villagers are proper Bayesians who, having learned from their mistakes, ignore the boy. The wolves have a field day, eating the flock, the boy, and his entire village.

I may have augmented Aesop’s classic fable with that last bit.

The boy is certainly a crushing failure at his job, but here’s the thing: the village is equally foolish, if not more so. The boy revealed his type, he’s bad at his job, but the village failed to react accordingly. They updated their beliefs but not their institutions. “We were good Bayesians” will look great on their tombstones.

They had three options.

A) Update their belief about the boy and ignore him.

This is what they did and look where that got them. Nine out of ten wolves agree that Good Bayesians are nutritious and delicious.

B) Update their beliefs about the boy, but continue to check on the flock when the boy raises the alarm.

They should have weighted their responses. Much like Pascal taking religion seriously because eternal torment was such a big punishment, you have to weight you expected probability of truth in the alarm against the scale of the downside if it is true. You can’t risk being wrong when it comes to existential threats.

C) Update their beliefs about the boy and immediately replace him with someone more reliable.

It’s all fine and good to be right about the boy being a lying jerk but that doesn’t fix your problem. You need to replace him with someone who can reliably do the job.

So this is a post about fascism. Some think that fascism is already here, others dismiss this as alarmism, others splititng the difference claiming that we are in some state of semi- or quasi-fascism. Within the claims that it is all alarmism, what I hear are the echoes of villagers annoyed by 50 years of claims that conservative politics were riddled with fascism, that Republicans were fascists, that everything they didn’t like was neoliberalism, fascism, or neoliberal fascism. Get called a wolf enough times and you might stop believing that wolves even exist.

Even if I am sympathetic, that doesn’t get you off the hook. It hasn’t been fascism for 50 years will look pretty on your tombstone.

Let’s return to our options

- A) Don’t believe the people who have been shouting about fascism for years, but take seriously new voices raising the alarm.

- B) Find a set of people who, exogenous to current events, you would and do trust and take their warnings seriously.

- C) Don’t believe anyone who shouts fascism, because shouting fascism is itself evidence they are non-serious people.

- D) Start monitoring the world yourself

Both A) and B) are sensible choices! If you’ve Bayesian updated yourself into not trusting claims of fascism from wide swaths of the commentariat, political leaders, and broader public, that’s fine, but you’ve got to find someone you trust. And if that leads you to a null set, then D) you’re going to have to do it yourself. Good luck with that. It takes a lot of time, expertise, and discipline not to end up the fascism-equivalent of an anti-vaxxer who “did their own research.”

Because let me tell you, C) is the route to perdition in all things Bayesian. Once your beliefs are mired in a recursive loop of confirmation bias, it’s all downhill. Every day will be just a little dumber than the one before. And that’s the real Orwellian curse of fascism.

What is the price of obvious lying?

Pushing beyond the despair and doomerism of “Nothing matters”, the question has never been is there a price for lying in politics, but rather what is the price of lying in politics. Note that “in politics” is doing a lot of heavy lifting here. In day to day life, the price of lying is the threat to your reputation. A reputaton for being untrustworthy is always very costly in the long run. But politics, however, has different layers across which the price of lying is heterogeneous. And yes, there are contexts where that price can go negative.

Put simply, what is the cost here? Is Greg Bovino, head of US Border Patrol, worried about his reputation? Is he worried about future personal legal liability? Is he worried about maintaining cooperative alignment across the administration and within the ranks of the Border Patrol and ICE? There’s a saying in politics – the worst thing you can do is tell the truth at the wrong time. But that’s more relevant to “lying by omission”, about simply abstaining from speaking on a subject so that you are not forced to choose between lying and paying a high political cost. This is different. I’m picking on this one person in the administration because Alex Pretti was summarily executed in the street in cold blood by a thicket of federal agents for the apparent crime of being in attendance and trying to help a woman while she was being pepper sprayed, but it is the subsequent lying that I am concerned with here. It follows a pattern that continues to darkly fascinate me.

Rather than simply “say nothing”, this administration has committed to the broad tactic of stating things that are factually, obviously untrue. That, more important, it is highly likely they know are untrue. That’s not something we’ve seen a lot of before. Politicians were known for being “slick” and “slippery”. For bending the truth, torturing the facts, or managing to fill entire press conferences without saying or committing to anything of substance. This administration, as I’ve said before, is different.

I see two likely explanations:

- The price of lying is zero because no one believes anything anymore. The truth is subjective and siloed.

- The price of lying is negative because constant and consistent commitment to the party can only be demonstrated by bearing the personal cost of telling obvious lies. In doing so you maintain the group, save yourself from being purged, and everyone in the group lives to fight another day. The net of which is a negative price for lying.

So what is it? Are we through the lol-nothing-matters looking glass, or are we witnessing an administration circle the wagons and solidify their committment to one another by blatantly lying on national television? I’m (perhaps obviously) of the belief that everything matters, that lying does have a cost, but the need for unity is so strong within this administration and it is, in fact, the lying that is holding it together. Until, of course, it doesn’t. Remember the most important lesson of The Folk Theorem – you can sustain cooperation in the Prisoner’s Dilemma, but only until you learn when the game is going to end. Then all bets are off.

Why ICE’s cruelty is only outpaced by their incompetence

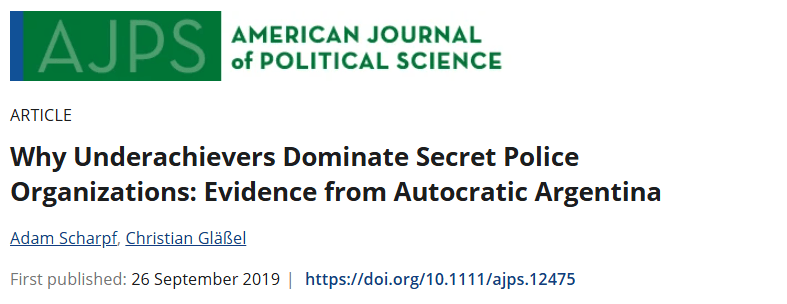

This paper has escalated from relevant to mission critical

From the summary:

“Who serves in secret police forces? Throughout history, units such as Hitler’s Gestapo, Stalin’s NKVD, or Assad’s Air Force Intelligence Directorate have been at the core of state repression. Secret police agents surveil, torture, and even kill potential enemies within the elite and society at large. Why would anyone do such dirty work for the regime? Are these people sadistic psychopaths, sectarian fanatics, or forced by the regime to terrorize the population? While this may be the case for some individuals, we believe that the typical profile of secret police agents is shaped by the logic of bureaucratic careers.”

The details and history in the paper are illuminating. The economic logic is simple, but it remains fascinating to be reminded of how far the reinforcing incentives of shame, power, and labor market demand can go when trying to understand the world. To recap the obvious

- For some the opportunity for cruelty is benefit and others a cost, no doubt heterogeneous across context for many (but not all). The selection effects into ICE officers is obvious.

- Shame selects as well. The larger the fraction of the American public that view ICE behavior as shameful and cruel, the fewer and more specific the individuals who will select in.

- Labor demand for individuals is heterogeneous in multiple dimension, but it always weaker for those who are broadly incompetent.

Combine those three and you get what we are observing: those with the weakest opportunities in the labor market are selecting into ICE service because they face the lowest opportunity cost. If there is a positive correlation between enjoying cruelty and weak labor market opportunties (which I am willing to believe there is. Few enjoy working with ill-adjusted, cruel people), then the broad incompetence selected into ICE ranks will be stronger. If being ill-adjusted and cruel limits the scale of your social network, leaving you isolated and lonely, then the expected shame of ICE services is lower, selecting for still greater cruelty within officers. Through this mechanism cruelty and incompetence don’t just correlate, they reinforce, until you are left with a very specific set of individuals exercising violent discretion.

To be clear this isn’t a complex or profound model. The individual insights are obvious, but it remains useful to consider them within the framework of a toy model because they emphasize how mutually-reinforcing incentives can create shocking institutional outcomes.

The Cooperative Corridor

The confluence of politics, recent interest in agent-based computational modeling, and Pluribus have convinced me now is the time to write about the “Cooperative Corridor”. At one point I thought about making this the theme of a book, but my research has become overwhelmingly about criminal justice, so it got permanently sidelined. But hey, a blog post floating in the primordial ether of the internet is better than a book that never actually gets written.

It’s cooperation all the way down

Economic policy discussions are riddled with “Theories of Everything”. Two of my favorites are the “Housing” and “Insurance” theories of everything. Housing concerns such huge fractions of household wealth, expenditures, and risk exposure that the political climate at any moment in time can be reduced to what policy or leader voters think is the most expedient route to paying their mortgage or lowering their rent. Similarly, the decision making of economic agents can, through a surprisingly modest number of logical contortions, always be reduced to efforts to acquire, produce, or exchange insurance against risk. These aren’t “monocausal” theories of history so much as attempts to distill a conversation to a one or two variable model. They’re rhetorical tools as much as anything.

My mental model of the world is that it is cooperation all the way down. Everything humans do within the social space i.e. external to themselves, is about coping with obstacles to cooperating with others. It is a fundamental truth that humans are, relative to most other species, useless on our own. There are whole genres of “survival” reality television predicated on this concept. If you drop a human sans tools or support in the wilderness, they will likely die within a matter of days. This makes for bad television, so they are typically equipped with a fundamental tool (e.g. firestarting flint, steel knife, cooking pot, composite bow, etc) after months of planning and training for this specific moment (along with a crew trained to intervene if/when the individual is on the precipice of actual death). Even then, it is considered quite the achievement to survive 30 days, by the end of which even the most accomplished are teetering on entering the great beyond. No, I’m afraid there is no way around the fact that humans are squishy, nutritious, and desperately in need of each other. Loneliness is death.

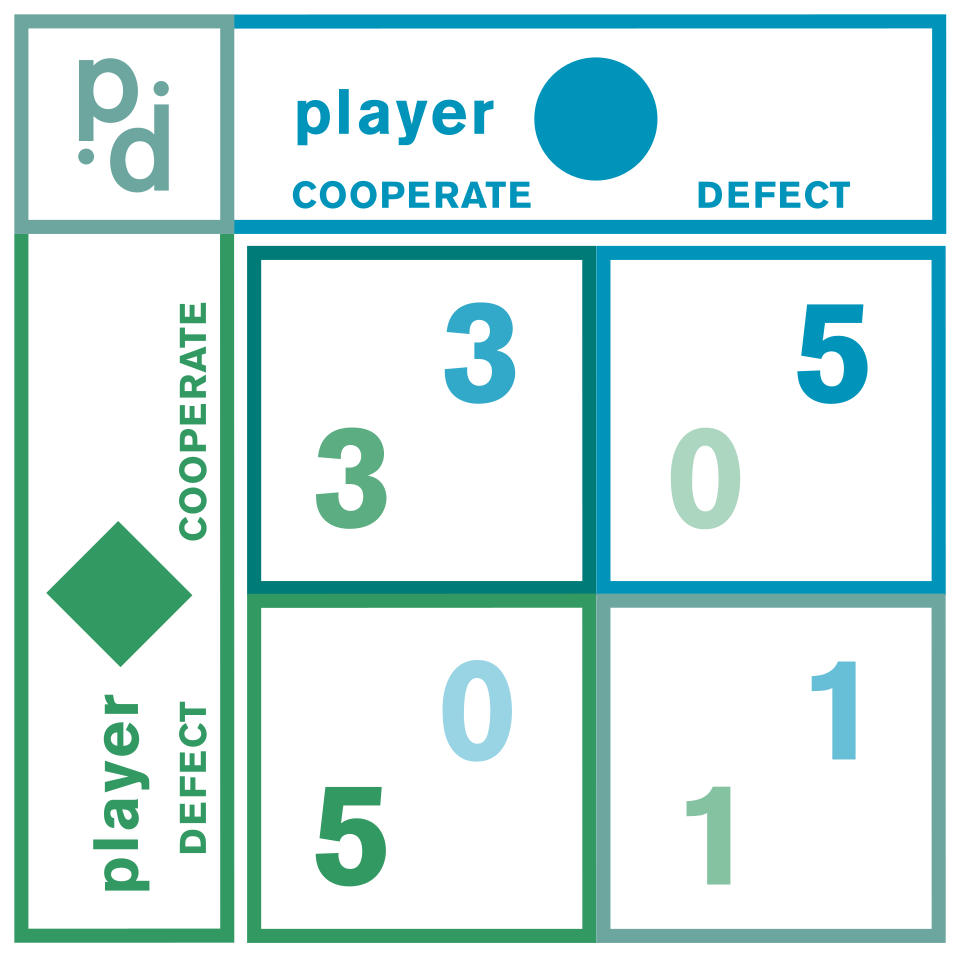

Counterintuitive as it may be, this absolute and unqualified dependence on others doesn’t make cooperation with others all that much easier. This is the lesson of the Prisoner’s Dilemma, that our cooperation and coordination isn’t pre-ordained by need or even optimality. Within a given singular moment it is often in each of our’s best interest to defect on the other, serving our own interests at their expense.

Which isn’t to say that we don’t overcome the Prisoner’s Dilemma every day, constantly, without even thinking about it. Our lived experience, hell, our very survival, is evidence that we have manifested myriad ways to cooperate with others despite our immediate incentives. What distinguishes the different spaces within which we carry out our lives is the manner in which we facilitate these daily acts of cooperation.

Kin

The first and fundamental way to solve the prisoner’s dilemma is to change the payoffs so that each player’s dominant strategy is no longer to defect but instead to cooperate. If you look at the payoff matrix below, the classic problem is that no matter what one player does (Cooperate or Defect), the optimal self-interested response is always to Defect. Before we get into strategies to elicit cooperation, we should start with the most obvious mechanism to evade the dilemma: to care about the outcome experienced by the other. Yes, strong pro-social preferences can eliminate the Prisoner’s Dilemma, but that is a big assumption amongst strangers. Among kin, however, it’s much easier. Family has always been the first and foremost solution. Parents don’t have a prisoner’s dilemma with their children. It doesn’t take a large leap of imagination to see how kin relationships would help familial groups coordinate hunting and foraging or il Cosa Nostra ensuring no one squeals to the cops.

Kinship remains the first solution, but it doesn’t scale. Blood relations dilute fast. I’m confident my brother won’t defect on me. My third-cousin twice removed? Not so much. The reality is that family can only take you so far. If you want to achieve cooperation at scale, if you want to achieve something like the wealth and grandeur of the modern world, you’re going to need strategies and institutions.

Strategies

There are many, if not countless, ways to support cooperation among non-kin. Rather than give an entire course in game theory, I’ll instead just enumerate a few core strategies.

- Tit-for-Tat = always copy your opponent’s previous strategy

- Grim Trigger = always cooperate until your opponent defects, then never cooperate again

- Walk Away = always cooperate, but migrate away from prior defectors to minimize future interaction

The Prisoner’s Dilemma is far, far easier to solve amongst players who can reasonably expect to interact again in the future. The logic underlying all of these strategies is commonly known as The Folk Theorem, which is the broad observation that all cooperation games are far easier to solve, with a multitude of cooperation solutions, if there is i) repeated interaction and ii) an indeterminate end point of future cooperation.

Strategies can facilitate cooperation with strangers, which means we can achieve far greater scale. But not as much as we observe in the modern world, with millions of people contributing to the survival of strangers over vast landscapes and across oceans. For that we’re going to need institutions.

Institutions

Leviathan is simply Thomas Hobbes’ framework for how government solves the Prisoner’s Dilemma. We concentrate power and authority within a singular institution that we happily allow to coerce us into cooperation on the understanding that our fellow citizens will be coerced into cooperating as well. That coercion can force cooperation at scales not previously achievable. It can build roads and raise armies. This scale of cooperation is the wellspring for both some of the greatest human achievements and our absolutely darkest and most heinous sins. Sometimes both at same time.

Governments can achieve tremendous scale, but there remain limits. My mental framing has always been that individual strategies scale linearly (4 people is twice as good as 2 people) and governments scale geometrically (i.e. an infantry’s power is always thrice its number). Geometric scaling is better, but governments always eventually run into the limits of their reach. Coercion becomes clumsy and sclerotic at scale. There’s a reason there has never been a global government, why empires collapse.

Markets can achieve scale unthinkable by governments because their reach is untethered to geography. Markets are networks. They scale exponentially. They solve the prisoner’s dilemma through repeated interaction and reputation. The information contained in prices supports search and discovery processes that both support forming new relationships while also creating sufficient uncertainty about future interactions. Cooperation is a dominant strategy. This scale of cooperation, of course, is not without critical limitations. Absent coercion there is no hope for uniformity or unanimity. No completeness. Public goods requiring uniform commitment or sacrifice are never possible within markets. The welfare of individuals outside of individual acts of cooperation (i.e. externalities) is not weighed in the balance.

There are other institutions that solve the prisoner’s dilemma. Religions, military units, sororities…the list goes forever. This article is already going to be too long, so I’ll start getting to the point. Much of the fundamental disagreement within politics and society at large is what comprises our preferred balance of institutions for supporting and maintaining cooperation, who we want to cooperate with, and the myths we want to tell ourselves about who we are or aren’t dependent on.

The Cooperative Corridor

Wealth depends on cooperation at scale. Wealth brings health and prosperity, but it also brings power. The “cooperation game” might be the common or important game, but it isn’t the only game being played. Wealth can be brought to bear by one individual on another to extract their resources. This is colloquially referred to as “being a jerk”. Perhaps more importantly, groups can bring their wealth to bear to extract the resources from another group. This is colloquially referred to as “warfare”.

Governments are an excellent mechanism for warfare. All due respect to the mercenary armies of history (Landsknechts, Condottieri, etc.), but markets are not well-suited to coordinate attack and defense. Which isn’t to say markets aren’t necessary inputs to warfare. This is, in fact, the rub: governments are good at coordinating resources in warfare, but markets are far better at generating those resources. A pure government society may defeat a pure market society in a war game, but a government-controlled society whose resources are produced via market-coordinated cooperation dominates any society dominated by a singular institution.

This all adds up to what I refer to as the Cooperative Corridor. A society of individuals needs to cooperate to grow and thrive. A culture of cooperation can be exploited, however, by both individuals who take advantage of cooperative members and aggressive (extractive) rival groups. Institutions and individual strategies have to converge on a solution that threads this needle. One answer might appear to be to simply cooperate with fellow in-group members while not cooperating with out-group individuals. This is no doubt the origin of so many bigotries—the belief that you can solve the paradox of cooperation by explicitly defining out-group individuals. Throw in the explicit purging of prior members who fail to cooperate, and you’ve got what might seem a viable cultural solution. The thing about bigotry, besides being morally repugnant, is that it doesn’t scale. The in-group will, by definition, always be smaller than the out-group. Bigotry is a trap. Your group will never benefit from the economies of scale as much as other groups that manage to foster cooperation between as many individuals as possible, including those outside the group.

As I noted in part II of my discussion of agent-based modeling, I published a paper a few years ago modeling how groups can thrive when they manage inculcate a culture of cosmopolitatan cooperation on an individual level, while supporting more aggressive (even extractive) collective insitutions. Cultures whose institutions and individual strategies exist within the corridor of cooperation will always be at an advantage. The point of the paper is decidedly not that we should aspire to being interpersonally cooperative and collectively extractive, but rather to demonstrate not just how cultures and institutions can, and often must, diverge. Institutions do not necessarily reflect an aggregation of the values or strategies held by individuals within a society. Quite to the contrary, selective forces in cultural evolution can push towards explicit divergence.

Pluribus

So what does this have to do with Pluribus?

[SPOILERS AHEAD if you haven’t watched through Episode 6]

You’ve been warned, so here’s the spoilers. An RNA code was received through space, spread across the human species, and now all but a handful of humans are part of a collective hive mind whose consciousnesses have been fully merged. That’s the basic part. The bit that is relevant to our discussion is the revelation that members of the hive mind 1) Can’t harm any other living creature. Literally. They cannot harvest crops, let alone eat meat. 2) They cannot be aggressive towards other creatures, cannot lie to them, cannot it seems even rival them for resources. 3) The human race is going to experience mass starvation as a result of this. Billions will die.

In other words, a cooperation strategy has emerged that spreads biologically at a scale it cannot support. It is also highly vulnerable to predation. If a rival species were to emerge in parallel, it would undermine, exploit, enslave, and eventually destroy it. The whole story borders on a parable of how a species like Homo sapiens could destroy and replace a rival like Homo neanderthalensis.

Cultural strategies are selected within corridors of success. Too independent, you die alone. Too cooperative, you die exploited. Too bigoted, you are overwhelmed by the wealth and power of more cosmopolitan rivals. Too cosmopolitan, you starve to death for failure to produce and consume resources. Don’t make the mistake of thinking the “corridor of success” is narrow or even remotely symmetric, though. On the “infinitely bigoted” to “infinitely cosmopolitan” parameter space, a society is likely to dominate it’s more bigoted rivals with almost any value less than “infinitely cosmopolitan.” So long as members of society are willing to harvest and consume legumes, you’re probably going to be fine (no, this isn’t a screed against vegetarianism, which is highly scalable. Veganism, conversely does have a much higher hurdle to get over…). So long as a group is willing to defend itself from violent expropriation by outsiders, they’re probably going to be fine. Only a sociopathic fool would see empathy as an inherent societal weakness. Empathy, in the long run, is how you win.

How this relates to political arguments

I almost wrote “current political arguments”, but I tend to think disagreements about institutions of cooperation are pretty much all of politics and comparative governance. We’re arguing about instititutions of in-group, out-group, and collective cooperation when we argue about the merits of property rights, regulation, immigration, trade, annexing territory, war. When we confront racism, nationalism, and bigotry, we we are fighting against forces that want to shrink the sphere of cooperation and leverage the resources of the collective to expropriate resources of those confined or exiled to the out-group. These are very old arguments.

The good news is that inclusiveness and cosmopolitanism are economically dominant. They will always produce more resources. But being economically and morally superior doesn’t mean they are necessarily going to prevail. The world is a complex and chaotic system. The pull towards entropy is unrelenting. And, in the case of cultural institutions and human cooperation, the purely entropic state is a Hobbesian jungle of independent and isolated familial tribes living short, brutish lives. Avoiding such outcomes requires active resistance.

Where do we find papers to read?

I was going to write a long post this week but time got short, so I went looking for new papers to skim through, put a few in my reading list, and then share one here. But Bluesky is bereft of new papers and Twitter isn’t even 3% of what it used to be. NBER working papers? Of course, but I’d desperately love to not have to resort to sharing the same working paper series that everyone else depends on and I don’t get to be a part of. Which is petty, yes, but it would nonetheless be great to tap other veins. I haven’t really figured out how to properly channel the SSRN digests that can feel at times like an entirely uncurate deluge. At the moment too much of my research diet is based in my personal network.

Are there accounts on bluesky I should be following? Or a particularly good SSRN digest? Or a substack I should be subscribing to? Or a Cuban coffee shop where cool social scientists hang out and share dope new papers?

Hit me up.

Part II: Why agent-based modeling could happen in economics. Eventually.

Three years ago I ruminated on why agent-based modeling never got any real traction in economics. It got a suprising amount of attention and I continue to receive emails about it to this day. I took care to explicitly punt on what the value-add of agent based models could and/or may yet be.

“ So why should economists give agent-based modeling another shot? That’s another post for another day. …

Well, today is that day, in no small part because this excellent thread led to a new batch of emails about my old post. Now, to be clear, that post was based on a solid decade of experience writing, presenting, and publishing papers built around agent-based models. This endeavor is far more speculative. I have a bit of prickly disdain for the genre of forecasting you find on “I’m not unemployed, I’m an Entrepreneur and Futurist” LinkedIn profiles, so I’ll ask you to indulge even more glibness than usual. With the cowardly caveats now out of the way, let’s get into it.

What are the advantages of agent-based models?

Deep heterogeneity, replicability, scale, flexibility, and time. There are different ways to frame it, but it all boils down to the fact that a multi-agent computational model does not require collapsing to statistical moments or limited heterogeneity (i.e. 3 or fewer types of agent) in order to “converge” or compute. It is not reliant on the single run of human history in order to postulate counterfactuals – you can run the model millions of times and observe the full distribution of outcomes. The population is not limited to the scale of the sample or the population – it can be as large as you can computationally handle. How flexibile can it be? Literally everything but the ur-text of the model can be endogenous. And time? Again, how long you run the model is limited only by computational capacity coupled with your own patience.

Do note that everything I just listed is also a disadvantage.

Agent-based modeling can be a new class of “meta-analysis”

The science of observing, distilling, interpreting, and even managing the scientific project is generally speaking the domain of statisticians and historians of thought. Interestingly, it’s been my experience that historians of economic thought were some of the biggest early enthusiasts for agent modesl (I even wrote a paper with one). I think there is an opportunity, however, to borrow from the logic of applied statistics used in the meta analysis of literatures.

Meta-analysis in economics is pre-demominantly constituted by reviews of empirical literatures that conduct statistical analysis of the coefficients estimated in regression equations across multiple papers. Comparisons across data sets, geographic and temportal settings, and statistical identification strategies allow practicioners, policy makers, and the curious public to better internalize the state of the literature and what it is actually telling us. These are valuable contributions not just because a decades work can be reduced to a paper reduced to an abstract reduced to a title that showed up in a google search conducted by an intern at the think tank recommending policy to a lawyer with good hair who won an election fourteen years ago. They are valuable because they fight against the current wherein we all are drawn to cherry-pick the empirical results that confirm our priors, particularly those that have a political valence associated with them. Meta-analyses have also shown the peculiar biases introduced by the career incentives in all social sciences – the seminal figure being the sharp cutoff in published p-values at traditional 0.05 “statistical significance” threshold.

To reiterate: these papers are useful, but they are also limited by the necessity to find like for like papers whose results can be compared. A framing must be set upon in advance within which the authors of the meta-analysis can curate the contributions to be included and collectively evaluated. Only when the analysis is completed can the authors take a step back and try to adjudicate what the collective results are and how they reflect upon any relevant bodies of theory. It is an inherently atheoretical exercise. There’s a reason schools of thought are rarely (ever?) upended by a meta-analysis that successfully adjudicates between competing models. There’s always just enough daylight between data estimation and a given model to resist acquiescing to claims that any analysis is testing a models validity.

Agent-based modeling offers the opportunity for meta-analysis of models. In an artificial world with millions of agents, we can program behavior that corresponds with different theories of labor markets, households, crime, addiction, etc. We can model markets characterized by monopoly, monopsony, and competition born of everything from government fiat to specific elasticities of substitution between goods. Hey now, hold your horses. A model of everything is a model of nothing. Once you allow for too much complexity, there’s no room for inference. It’s just noise.

Yes, of course. You can’t model everything. But there is a greater opportunity to find when models are mutually incompatible. Incongruent. Is there a way to run an artificial city of a million agents to formulate a social scientific theory of everything? Absolutely not. But it would be interesting if a million runs of a million models shows that you can never have both a highly monopsonistic labor market and a income-driven criminal market because the high substitutability of cash across sources necessary in the criminal market allows for the kind of Coasean bargains that undermine monopsony. To be clear, I just made that up. But there’s room for as yet unseen cross-pollination across bodies of applied theory.

Pushing the Lucas critique all the way to the hilt

This is essentially a recursive version of modern macroeconomics where agents within the model learn the results being reported in the paper about the model they inhabit, changing their behavior accordingly. Wait, isn’t that just the definition of “equilibrium”? I mean, we already have the Lucas Critique. Yes, but we typically have very well-behaved agents in those models. What if they are a bit noisier in their heterogeneity? What if they took suboptimal risks, many failed, but some won? What if there was an error term in their perceptions of the world i.e. they ran incomplete regressions, observed the results, and then treated the results as a sufficient approximation of the truth? Essentially a behavioral world where agents are often smart but sometimes unwise? Where the churn of human folly and hubris undermined equilibrium while fueling both suffering and growth. A story of Schumpeterian economic growth told by the iterating arcs of Tolstoy and Asimov.

No, I said all the way

I’m not sure if what I just described is just the kind of advanced macroeconomics I am currently ignorant of or complete nonsense. Possibly both. To be clear, I’m deeply skeptical of the preceding paragraphs. One of the ironies of complexity science is that those who take it seriously know that overly complex theoretic ambitions are the death of good science. No, I think if you really want to apply agent-based methodologies within economics, it is best to go in the opposite direction. Simpler models let loose in larger, less constrained sandboxes.

Almost a decade ago Paul Smaldino and I wrote a paper about how groups collectively evolve separate strategies for internal and external cooperation. It’s a cool paper, I’m proud of it, and I kinda, sorta think its a major plotline in “Pluribus“. No, I don’t think the writers are aware of our paper. Yes, I know I sound like a crazy person, but I think the model we designed and explored is relevant to the story they are telling. Maybe next week I’ll lay out the parallels now that season one is complete.

Our paper is a simple story where i) evolutionary pressure on a couple of simple parameters for behavior at the individual level, ii) combined with parameters for how collective behavior emergers from individual pressure, can lead to iii) a world where a society of nice people can be, collectively, quite vicious. The evolutionary pressue is subtle, but also simple. Populations of uncooperative people fail to scale their resources and die off. Populations of cooperative people thrive until they are confronted by aggressive collectives that exploit and expropriate from them, killing them off. But if a group somehow evolves a culture in which members cooperate internally and externally on an individual level, while also being difficult to exploit collectively- if they thread that needle, they thrive.

I think there’s an opportunity for agent-based models within economics to do what we did in our model, but much bigger and much better. Framed as a question: why are the agents in our model only varying along simple parameters? Why aren’t they varying in the complexity of their behavior? Why aren’t they evolving their own rich, multi-layered strategies? Why aren’t they evolving strategies based on their own predictions for not just individual behavior, but how they think that behavior will change the landscape of resources and institutions in the collective? Why they are only playing the game we laid out, choosing amongst the strategies we gave them?

For me, the seminal moment when AI became something worth considering was not as far back as when computers beat players at chess or last week when LLMs were used to fabricate college application essays. It was in 2017 when AlphaGo Zero arrived at a level of play in Go that surpassed grand champions without any outside information besides the rules for the game. It was very specifically not an LLM as I understand them. It learned only by playing against itself. It created knowledge and insight strictly be internally iterating within a set of rules that evaluated success and failure.

We don’t know how to model an entire economy. Apologies to those interested in the Sante Fe Artificial Stock Market, but that’s always been too complex for my blood. So, again, we don’t know enough to make an agent-based model of an entire economy from the ground up, but we do know the rules of evolutionary success (survival and reproduction) and market success (resources and risk). We also have rules that we are comfortable imposing on emotional, sympathetic, and empathetic success (quantity and intensity of interpersonal relationships, observation of other’s success, the absence of suffering). Add in a few polynomial parameters for shape of utility, disutility, and you’ve got a context where agents will learn how to play whatever games you throw at them.

So why not simpy set the rules in place, build a million agents in a world of other agents forced to play games in a world of interactive games? The twist, of course, is that their strategies start as a blank slate.

Step 1: randomly match with another

Step 2: randomly choose to interact or not

Step 3: If you interact, randomly chooes to cooperate or not

Step 4: Go to 1The question is, can you make the agents smart enough to update and add to those 4 lines of code in a manner that could evolve complex behavior, but not so rigid or intelligent that emergent strategies are obvious from the get go? Can you write a model where not only the strategies being played are endogenous, but the games themselves? There’s at least two people who already think the answer may be yes. And, yes, that paper is exceptionally cool, even if they consider their model outside the rubric of agent-based models.

Is this an AI thing? Because it sounds like an AI thing

Again, we find ourselves in a meta-enterprise relative to the field as it stands, only now we’re talking about game theory and evolutionary behavioral economics where the human contribution is at the meta level – the ur text of the model where rules and parameters serve as a substrate upon which something new can emerge. New, but replicable. Something that you can work backwards from, through the simulated history, to reverse engineer the mechanism underlying the outcomes.

Economics is riding high (as a science, at least. Less so as as policy advocates.) The credibility revolution and emphasis on causal inference placed it in an ideal position to make contributions in what is a golden age of data availability. Before all this, however, was an era of high theory, one where macroeconomists formed schools of thought and waged wars of across texts. It’s no dougbt too conveniently cyclical to predict a new era of high theory on the horizon, but that’s what agent-based models could offer. A new era of theory, only this time centered around microeconomics, where milllions of deeply heterogenous agents are brought into being in a sandbox of carefully selected rules and hard parameters, where those rules and parameters are varied across millions of runs, and the model is run millions of time in parallel, each run a wholly fabricated counterfactual history.

Will the model replicate and explain our world? Almost assuredly not. But the models and strategies the agents come up with? Those could be entirely new. And that’s what the next era of high theory needs more than anything else. Not just new models. New sources of models.

New models for inventing models.

If you aspire to management, learn to spot half-assed AI workflow

First, yes, the commenter is correct, this is grim:

The tragedy of needlessly lost lives is, of course, bad enough to despair, but it’s made that much worse that false information created to ostensibly (and obviously) prevent a Muslim man from being credited with the kind of heroism normally reserved for films* is so casually distributed through major social media channels. Putting despair aside (easier said than done), I’m not interested in only shaming twitter et al for promulgating false narratives that always seem to conveniently fit into Grok’s preferred narratives of white/western supremacy. I’m more interested in thinking about how our processing of information will evolve.

There is always selective pressure in labor and life for those who better adapt to a changing technological and information landscape, and there’s no shortage of change happening right now. Some of it falls into classic “resist the propaganda” tropes. Don’t believe what you see on TV has evolved to don’t believe what you learn from the internet→ social media→AI→??? Once again, easier said than done, and I think it is more nuanced than that. It’s not just about information insulation and nihilism, it’s about cultivating the ability to better intuit when you are being misled.

Is there a subreddit? Of course there is a subreddit:

The comments are interesting because they are collectively sussing out specific, tangible clues that this is or isn’t AI. The convenient lack of license plates is both evidence of an error (if the state requires front license plates) and one of selective deception (the left car has their plate cropped out rather than blurred out). There is also the uncanny over-simplicity of the setting. No other people, debris, trash cans, mailboxes, etc. The absolute perfection of the cars outside of the region immediately surrounding the point of collision.

We have intuitive tools at our disposal, likely borne out of the same cogntive sources of the “uncanny valley” that haunts certain animation. We may have evolved to avoid predators that used mimicry to approach and infiltrate. These skills are ancient and innate, though. They are not inherently honed to combat AI-generated and distributed deception. We will have to evolve. And, as alluded to earlier, this is going to show up in far more than our politics.

There’s lots of hype around training students to work with AI. That’s all well and good, but I’m not sure how different those tools are than the ones that we honed to search with Google, to write and debug our own code, or to simply write effectively. What about the skills to evaluate and credit inputs? To discern the product of narrow expertise from distilled generalizations i.e. to discern new workflow and products from recycled “AI slop”. How much of a manager’s job is to simple assess whether the task was completed sufficiently or half-assed 70% of the way there? A lot of it? Most of it? The thing about half-assing it is that you are only incentivized to do it when avoiding 50% of the toil is worth the risk of getting caught. What happens when you can avoid 95% of the toil? Basic economics says you’re going to half-ass it a lot more unless the probability of getting caught or the punishment increases. What that means is that if management doesn’t get better at identifying 5%-assed AI slop from employees they’re going to have to start firing employees when they do get caught. In a world with high separation costs, that’s not an attractive option. Which means tilting the balance of decision-making back towards “actually doing the work” will fall to improved managerial oversight and monitoring. There’s no shortage of handwringing over escalating C-suite salaries. It will be interesting to how people respond to wage scales rebalancing towards middle management.

The most cliched thing to ask for in a job applicant has long been “attention to detail” or that they be “detail oriented”. I’m not sure if that is now obsolete or more important than ever. It’s not just about attention, per se. It’s evaluation, perhaps even cynicism. And it’s not because AI is evil or corrupt or even wrong. It’s just overconfident, and that overconfidence is catnip for anyone who wants to believe their work for the day is done at 9:05am. If you want to be in charge, you’re going to have to get really good at sussing out the little signs that what you’re looking at wasn’t produced for your task, but the average of all similar tasks. Can you look quickly and closely? You’re the boss, you’re busy, but so you better be good at it. The AI is in the details.

*And seriously, Ahmed al Ahmed is a hero. A movie hero. A crawling through the air ducts to fight the bad guys hero. Unarmed, he tackled a man actively firing a rifle at innocents and in the process saved a number of lives we will never know. He was shot twice. He’s real. I am in awe.