My parents have moved into an elder community. Having a passing familiarity with nursing homes of decades past and elder care scams of decades current, my family spent considerable time researching options, reputations, and legal concerns. Now that it is done, however, I have sufficient peace of mind to make broader reflections.

The resulting institutions essentially looks like a hybrid college campus/country club, albeit less concerned with status projection than the different manners in which a human might lose their balance. More importantly, however, it is a small scale reminder of the powers of agglomeration and returns to scale. My middle class parents now enjoy greater total amenities than they ever have in their entire life, some for the first time ever. I assure you that it is the rare government engineer to who spends their prime earning years with a heated olympic swimming pool, jacuzzi, steam room, sauna, and modern gym equipment within 200 steps of their front door. A separate restaurant, cafeteria, and bakery sit on the campus. Community transit is available 12 hours a day to connect them to the broader region, but live culture, education, and entertain appear as daily options within each building. I won’t get into the myriad physical and mental healthcare options, but they’re there in spades.

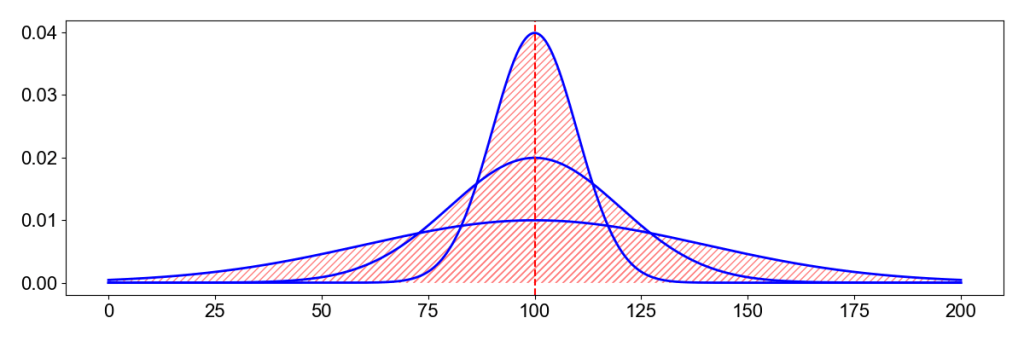

Essentially my parents are living a city for the first time in 50 years. A small, niche catered, contract-chartered city, but a city nonetheless. It’s amazing how many amenities become affordable when you only have to pay for a 100th, 1000th, or 10,000th of the underlying cost of provision.

This raises some questions. First of all, why don’t more of us live like this? Which, with a little reflection, is simply asking why more people don’t live in cities, which in turn invites standard answers regarding preferences for more space and fewer neighbors while also further highlighting the immense costs of 40 years of construction and density obstructionism.

The more interesting question, I believe, is how many of us are going to live like this? When octogenerians peak as a fraction of the population, will we see a new golden age of agglomeration, but in private communities instead of cities? What sort of scales might these communities achieve? Will Boomers rediscover their affection for transit, but as a private club good rather than a government-provided public good? Will generations of rural and suburban Americans find themselves living in cluster micro-cities surrounding major cities, enjoying trips daytime trips into the very urban areas they’ve previously feared were overrun with imagined crimewaves? Who is going to run for mayor? What sort of power is constitutionally invested in the mayor of city whose citizens pay a flat tax i.e. community fees i.e. rent?

What’s going to happen when the Boomers pass on and subsequent Generation X members show up with greater urban affinities, but smaller numbers and fewer children to support them? Will some elder communities collapse and be absorbed into a smaller number of larger elder cities, breeding greater scale returns, but within the economic security of a generation of grown children to foot the bill if the money runs out? Will there be an Orange Julius and Tower Records for me to hang out at? Will chain wallets come back?

Come to think of it, why are we waiting until our 80s? What’s stopping us from living in tightly-knit condominium communities filled to the brim with the social and community public goods that increasingly lonely Americans seem to be in desperate need of? Why can’t I go on reddit and find the apartment complex whose emergent culture of tenants caters to my households specific interests in games, art, and sports?

I started this worried about how my parents were going to live and finished trying to figure out how to live more like them. What I’m saying is the YIMBYs need to win and make it snappy so my household can live its dream of living in a 3 bedroom condo on the 5th floor of a building built on top of the Startcourt mall.

Addendum: I am not the first person to think along these lines.