In my Inbox I read the following sentence, summarizing an article on child health in Arkansas: “The latest Annie E. Casey Foundation KIDS COUNT Data Book shows 2022 was the deadliest year on record for child deaths in Arkansas.”

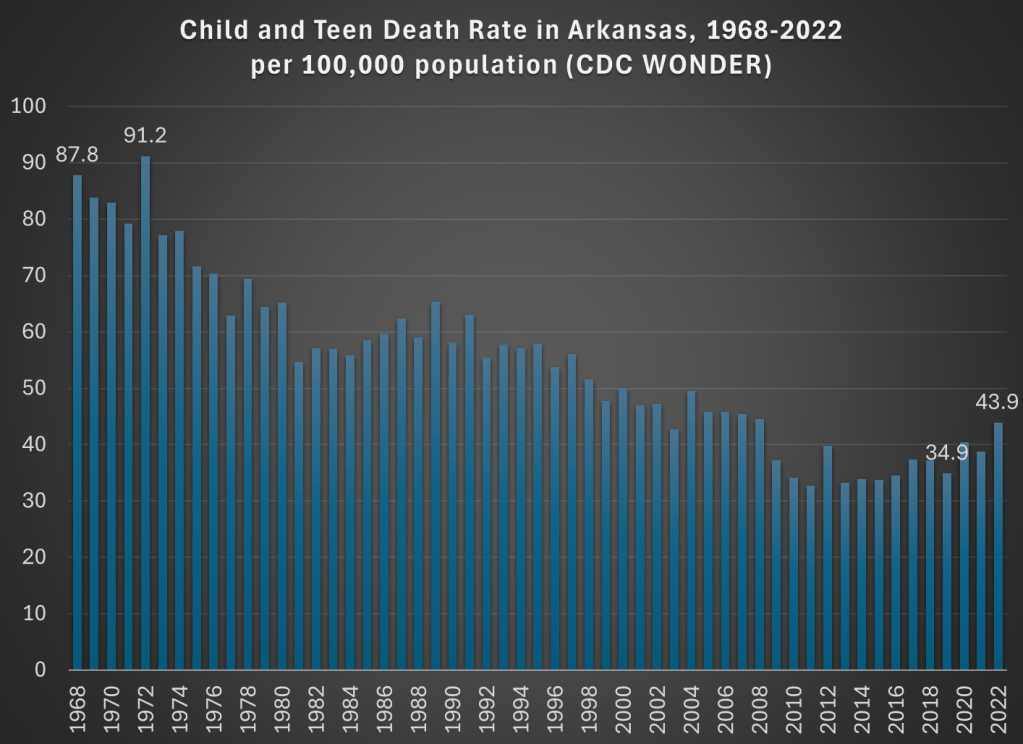

Deadliest on record! That certainly grabbed my attention. I clicked the link and read the article. Indeed, they emphasize three times that 2022 was the “deadliest year” for kids in Arkansas, including with a chart! And the chart does seem to support the claim: in 2022 there were 44 child and teen deaths per 100,000 in Arkansas, higher than any year on the chart.

But wait a minute, this chart only goes back to 2010. Surely the record goes back further than that? Indeed it does. It took me three minutes (yes, I timed myself, and you have to use 4 different databases) to complete the necessary queries from CDC WONDER to extract the data to replicate their 2010-2022 chart, and to extend the data back a lot further: all the way to 1968 (though in 30 seconds I could have extended it back to 1999).

And what do we find in 1968? The death rate for children and teens in Arkansas was twice as high as it was in 2022. Not just a little higher, but double. With some more digging, I might be able to go back further than 1968, but from the easily accessible CDC data, that’s as far back as “the record” goes. Of course, I knew where to look, but I would hope that a group producing a data book on child health also knows where to look. And you don’t need to extend this very far past the arbitrary 2010 cutoff in the article quoted: 2008 and every year before it was more deadly than 2022 for children in Arkansas. Here’s a chart showing the good long-run trend:

Now there is a notable flattening of the long-run trend in the past 15 years or so, and a big reversal since 2019. What could be causing this? The article I read doesn’t get specific, but here’s what they say: “The state data isn’t broken out into cause of death, but firearm-related deaths have become the leading cause of death among U.S. teens in recent years. Deaths from accidents such as car crashes account for most child deaths.”

But using CDC WONDER, we can easily check on what is causing the increase since 2019. “Firearm-related deaths” is an interesting phrase, since it lumps together three very different kinds of deaths: homicides, suicides, and accidents. And while it is true that “deaths from accidents” are the leading category of deaths for children, this also lumps together many different kinds of deaths: not only car crashes, but also poisonings, drownings, or accidental firearm deaths.

For Arkansas in 2022, here are the leading categories of deaths for children and teens (ages 1-19) if we break down the categories a bit:

- Homicides: 66

- Non-transport accidents: 58 (largest subcategories: poisonings/ODs and drowning)

- Transport accidents: 52 (almost all car crashes)

- Suicides: 24

- Birth defects: 16

- Cancers: 14

- Cardiovascular diseases: 13

And no other categories are reported, because CDC WONDER won’t show you anything smaller than 10 deaths.

We might also ask what caused the increase since 2019, especially since this a report on child health and possible solutions. The death rate increased by 9 deaths per 100,000, and over 80% of the increase is accounted for by just two categories: homicides and non-transport accidents. Car crashes actually fell slightly (though the rate increased a bit, since the denominator was also smaller). Deaths from suicides, cancer, and heart diseases also declined from 2019 to 2022 among children in Arkansas, and these are the three on the list above that we would probably consider the “health” categories. Things actually got better!

But the really big increase, and very bad social trend, is the category of homicides. Among children and teens in Arkansas, it rose from 35 deaths in 2019 to 66 deaths in 2022. It almost doubled. That’s bad! But homicides are not mentioned anywhere in the article on this topic that I read (“firearm-related deaths” is the closest they get). And while car accidents are definitely a major problem, they didn’t really increase from 2019 to 2022 (among kids in Arkansas).

One more thing we can do with CDC WONDER is break down the homicides by age. The numbers so far are looking at a very broad range of children and teens, from ages 1-19. As I’ve written about before, the is a huge difference between homicide rates for older teens versus all of the kids. Indeed for Arkansas we see the same pattern, such as when I run a CDC WONDER query for single-years of age: only the ages 17, 18, and 19 show up (remember, anything less than 10 deaths won’t register in the query).

Breaking it down by five-year age groups, we see that 53 of the 66 homicides (in Arkansas among kids and teens) were for ages 15-19, that is 80% of the total. And further if we run the query by race, we see that 40 of the 66 homicides were for African Americans age 15-19. This is clearly a social problem, but it’s an extremely concentrated social problem. And the increase for older teen Blacks has been large too: it was just 17 deaths in 2019, more than doubling to 40 homicides in 2022.

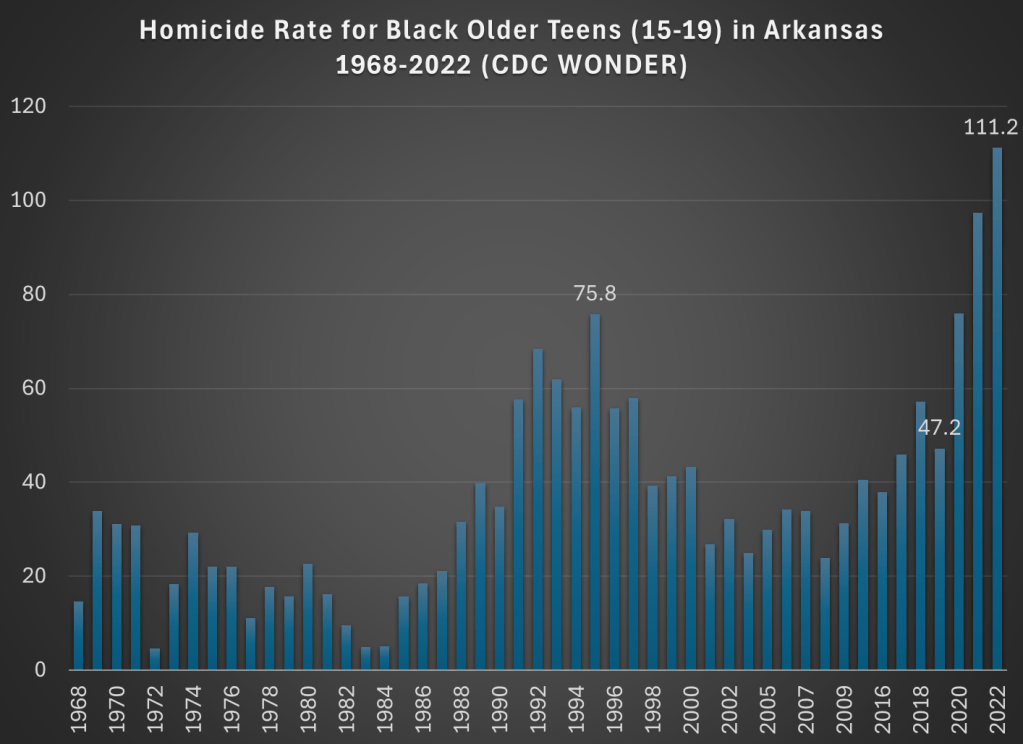

Now, small numbers can jump around a bit, so just looking at 2019 and 2022 might be deceptive. What if we had a longer annual series to look at? Again, CDC WONDER allows us to do this. Here is the chart for homicides among older Black teens in Arkansas:

This is a dramatic chart. The steady rise in homicides among this demographic since 2019 is staggering. Not only the dramatic increase, but notice that 2021 and 2022 are much worse than the crime wave of the early 1990s, which also jump out in this chart. The homicide rate for older Black teens in 2022 was almost 50 percent higher than 1995, the prior worst year on record.

So is there a problem with child and teen deaths in Arkansas? Yes! But with just a few minutes of searching on CDC WONDER, I think we can get a much better picture of what is causing it than the article I read summarizing the report. Indeed, if we read the full national report, the word “homicide” is only mentioned once in a laundry list of many causes of death.

The most important part of addressing a social problem, such as “deadliest year on record for child deaths in Arkansas” is to know some basic details about what is causing a bad social indicator to worsen. Hopefully after reading this blog post you know a little bit more. If you want to read my summary of the research on how to reduce deaths from firearms, see this June 2022 post.