Last weekend brought me back to Temple University, ten years after graduating, for a conference of econ PhD alums. I had so many reactions:

- Mixing a research conference with what is effectively a reunion or homecoming is a great idea for a PhD program, and more schools should do it. It brought together alumni from all different years, but it especially felt like a reunion to me since it’s been ten years since I graduated (not that I really know about reunions; I’ve never been to a high school or college one).

- Philadelphia in general and Temple University in particular have gotten much nicer (though still gritty). Some of this I expected; the country is getting steadily richer, and it seems like every college is always on a building spree. But as with New Orleans, it is a city still well below its peak population that I first got to know in the aftermath of the great recession. Unemployment in Philly is now well under half what it was the whole time I lived there, and it shows.

- Life is short. I was saddened, but not shocked, to hear that one of my professors had died. I was saddened and shocked to hear that one of my fellow students had.

- As a kid, whenever I went back to one of my old schools, I usually felt nostalgia mixed with the feeling that everything seemed small. Then I thought this smallness was only about me having grown taller, but now I wonder. At Temple the economics department has changed buildings, but when I went back to the old building everything seemed small, despite me being the same size I was in grad school. But at the time the building loomed so large in my mind; I was so focused on the things that happened there, the classes and tests, the study sessions and writing in the computer lab, what the professors thought, and everything that it all represented. All that apparently made the rooms seem physically larger in a way they now don’t once I have graduated and the professors moved.

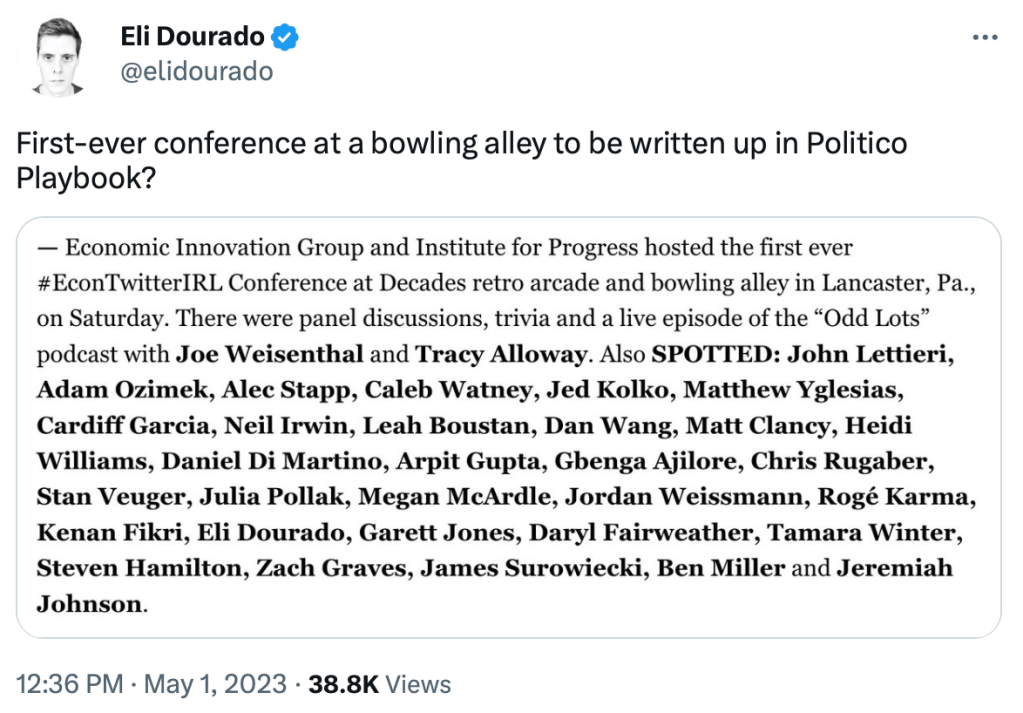

- Temple PhDs are much more successful than I would have guessed at the time. It was hard for students attending what was then a bottom-ranked program during the Great Recession to be optimistic about our job prospects, especially when we worried we might fail out of the program (a valid concern when, afaik, only 4 of the 11 students in my year finished their PhDs). But things turned out great; just in the past 10 years from a small program there are many people who are tenured or tenure track at decent schools, who have research or important supervisory positions at the Fed, or who are making a name for themselves in the private sector (like Adam Ozimek).

- Why have we so exceeded our low expectations? The improving economy helped. Economics PhDs from anywhere turned out to be a valuable degree. Perhaps our training was stronger than we gave it credit for at the time. I see two main tracks for success coming out of a lower-ranked program, where the school’s name alone might not open doors:

- publish a lot (my strategy), or

- find some way to get your foot in the door of a major institution like the Fed system or a major bank, then work your way up. The initial way in could be something less competitive, like an internship or a job you don’t necessarily need a PhD for. But once you are in you will be judged mostly on your performance within the institution, not your credentials. In a panel on non-academic jobs, several alums emphasized that conditional on having enough technical skills to get hired, at the margin people/communication skills are much more important to advancement than further technical skills.

- Temple’s economics PhD program paused admissions back in 2020, but is aiming to restart with a redesigned program in 2025.