Please see my latest paper, out at Public Choice: Effort transparency and fairness

The published version is better, but you can find our old working paper at SSRN “Effort Transparency and Fairness”

Abstract: We study how transparent information about effort impacts the allocation of earnings in a dictator game experiment. We manipulate information about the respective contributions to a joint endowment that a dictator can keep or share with a counterpart…

Employees within an organization are sensitive to whether they are being treated fairly. Greater organizational fairness is shown to improve job satisfaction, reduce employee turnover, and boost the organization’s reputation. To study how transparent information impacts fairness perceptions, we conduct a dictator game with a jointly earned endowment.

The endowment is earned by completing a real effort task in the experiment, an analog to the labor employees contribute to employers. First, two players work independently to create a pool of money. Then, the subject assigned the role of the “dictator” allocates the final earnings between them.

In the transparent treatment, both dictators and recipients have access to complete information about their own effort levels and contributions, as well as those of their counterparts. In the non-transparent treatment, dictators have full information about the relative contributions of both players, but recipients do not know how much each person contributed to the endowment. The two treatments allow us to compare the behaviors of dictators who know they could be judged and held to reciprocity norms with dictators who do not face the same level of scrutiny.

*drumroll* results:

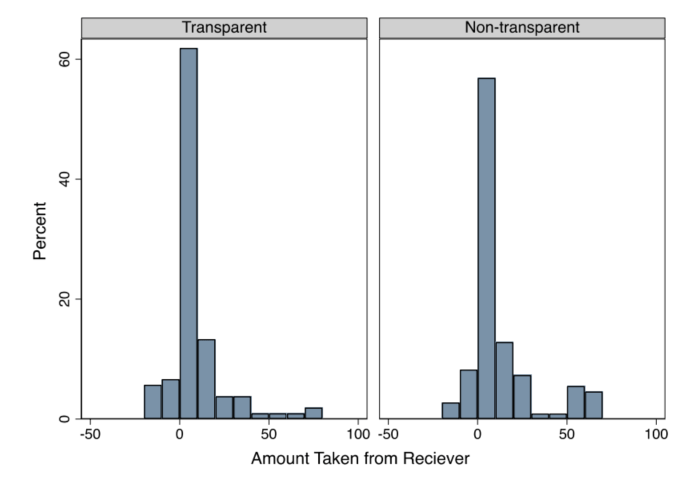

This graph shows the amount of money the dictators take from the recipient contribution, in cents. There are two ways to look at this. Notice the spike next to zero. Most dictators do not take much from what their counterpart earned. They are *dictators*, meaning they could take everything. Most take almost nothing, regardless of the treatment. We interpret this to mean that they are acting out of a sense of fairness, and we apply a humanomics framework to explain this in the paper.

Also, there is significantly more taken in non-transparency. When the worker does not have good information on the meritocratic outcome, then some dictators feel like they can get away with taking more. Some of this happens through what we call “shading down” of the amount sent by the dictator under the cover of non-transparency.

There is more in the paper, but the last thing I’ll point out here is that the “worker” subjects (recipients) anticipate that this will happen. The recipients forecast that the dictator would take more under non-transparency. In our conclusion, we mention that, even though the dictator seems to be at an advantage in a non-transparent environment, the dictator still might choose a transparency policy if it affects which workers select into the team.

View and download your article* This hyperlink is good for a limited number of free downloads of my paper with Demiral and Saglam, says Springer the publisher. Please don’t waste it, but if you want the article I might as well put it out there. I posted this on 11/2/2024, so there is no guarantee that the link will work for you.

Cite our article: Buchanan, J., Demiral, E.E. & Sağlam, Ü. Effort transparency and fairness. Public Choice (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-024-01230-9