Anyone who reads financial headlines knows that gold prices have soared in the past year. Why?

Gold has historically been a relatively stable store of value, and that role seems to be returning after decades of relative neglect. Official numbers show sharply increased buying by the world’s central banks, led by China, Poland, and Azerbaijan in early 2025. Russia, India and Turkey have also been major buyers. There is widespread conviction that actual gold purchases are appreciably higher than the officially-reported numbers, to side-step President Trump’s threatened extra tariffs on nations seen as de-dollarizing.

I think the most proximate cause for the sharp run-up in gold prices in the past twelve months has been the profligate U.S. federal budget deficit, under both administrations. This is convincing key world actors that the dollar will become increasingly devalued over time, no matter which party is in power. Thus, it is prudent to get out of dollars and dollar-denominated assets like U.S. T-bonds.

Trump’s erratic and offensive policies and statements in 2025 have added to the desire to diversify away from U.S. assets. This is in addition to the alarm in non-Western countries over the impoundment of Russian dollar-related assets in connection with the ongoing Russian invasion of Ukraine. Also, there is something of a self-fulfilling momentum aspect to any asset: the more it goes up, the more it is expected to go up.

This informative chart of central bank gold net purchasing is courtesy of Weekend Investing:

Interestingly, central banks were net sellers in the 1990s and early 2000s; it was an era of robust economic growth, gold prices were stagnant or declining, and it seemed pointless to hold shiny metal bars when one could invest in financial assets with higher rates of return. The Global Financial Crisis of 2008-2009 apparently sobered up the world as to the fragility of financial assets, making solid metal bars look pretty good. Then, as noted, the Western reaction to the Russian attack on Ukraine spurred central bank buying gold, as this blog predicted back in March, 2022.

Private investors are also buying gold, for similar reasons as the central banks. Gold offers portfolio diversification as a clear alternative from all paper assets. In theory it should offer something of an inflation hedge, but its price does not always track with inflation or interest rates.

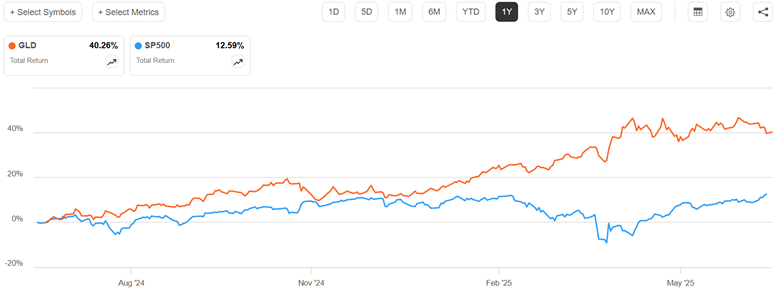

Here is how gold (using GLD fund as a proxy) has fared versus stocks (S&P 500 index) and intermediate term U. S. T-bonds (IEF fund) in the past year:

Gold is up by 40%, compared to 12.6% for stocks. That is huge outperformance. This was driven largely by the fact that gold rose strongly in the Feb-April timeframe, while stocks were collapsing.

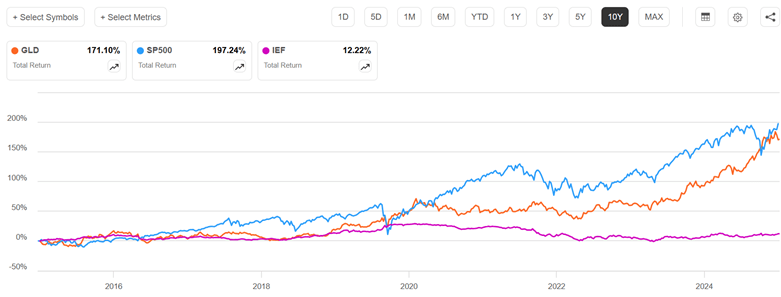

Below we zoom out to look at the past ten years, and include the intermediate-term T-bond fund IEF:

Gold prices more than doubled from 2008 to 2011, then suffered a long, painful decline over the next two years. Prices were then fairly stagnant for the mid-2010s, rose significantly 2019-2020, then stagnated again until taking off in 2023. Stocks have been much more erratic. Most of the time stock returns were above gold, but the 2020 and 2024 plunges brought stocks down to rough parity with gold. Since about 2019, T-bonds have been pathetic; pity the poor investor who has been (according to traditional advice) 40% invested in investment-grade bonds.

How to invest in gold? Hard-core gold bugs want the actual coins (no-one can afford a full bullion bar) to rub between their fingers and keep in their own physical custody. You can buy coins from on-line dealers or local dealers. Coins are available from the U.S. Mint, but reportedly their mark-ups are often higher than on the secondary market.

An easier route for most folks is to buy into a gold-backed stock fund. The biggest is GLD, which has over $100 billion in assets. There has long been an undercurrent of suspicion among gold bugs that GLD’s gold is not reliably audited or that it is loaned out; they refer derisively to GLD as “paper gold” or gold derivatives. The fund itself claims that it never lends out its gold, and that its bars are held in the vaults of the custodian banks JPMorgan Chase Bank, N.A. and HSBC Bank plc, and are independently audited. The suspicious crowd favors funds like Sprott Physical Gold Trust, PHYS. PHYS is claimed to have a stronger legal claim on its physical gold than GLD. However, PHYS is a closed-end fund, which means it does not have a continuous creation process like GLD, an open-end ETF. This can lead to discrepancies between the fund’s share price and the value of its gold holdings. It does seem like PHYS loses about 1% per year relative to GLD.

Disclaimer: Nothing here should be taken as advice to buy or sell any security.