With the arrest of Venezuelan President Maduro, the US is potentially attempting to remake the institutions of yet another country. I say potentially because, as of now, all that has happened is that Maduro was removed. His VP stepped in to replace him, and it appears that, for now, the rest of the structure of government is in place.

Nonetheless, any time the US intervenes in the affairs of another country, it brings back the old debates about regime change, nation building, exporting democracy, etc. Many want to discuss the legal and moral implications of these actions — and these are certainly worth discussing! — but as social scientists we should also ask “does it work?”

For example, one excellent paper on regime change via CIA covert intervention is from Absher, Grier, and Grier. They look at five cases during the Cold War in Latin America of CIA-sponsored regime change, and find moderate declines in income and large declines in democratic institutions. Not a good case for regime change and exporting democracy!

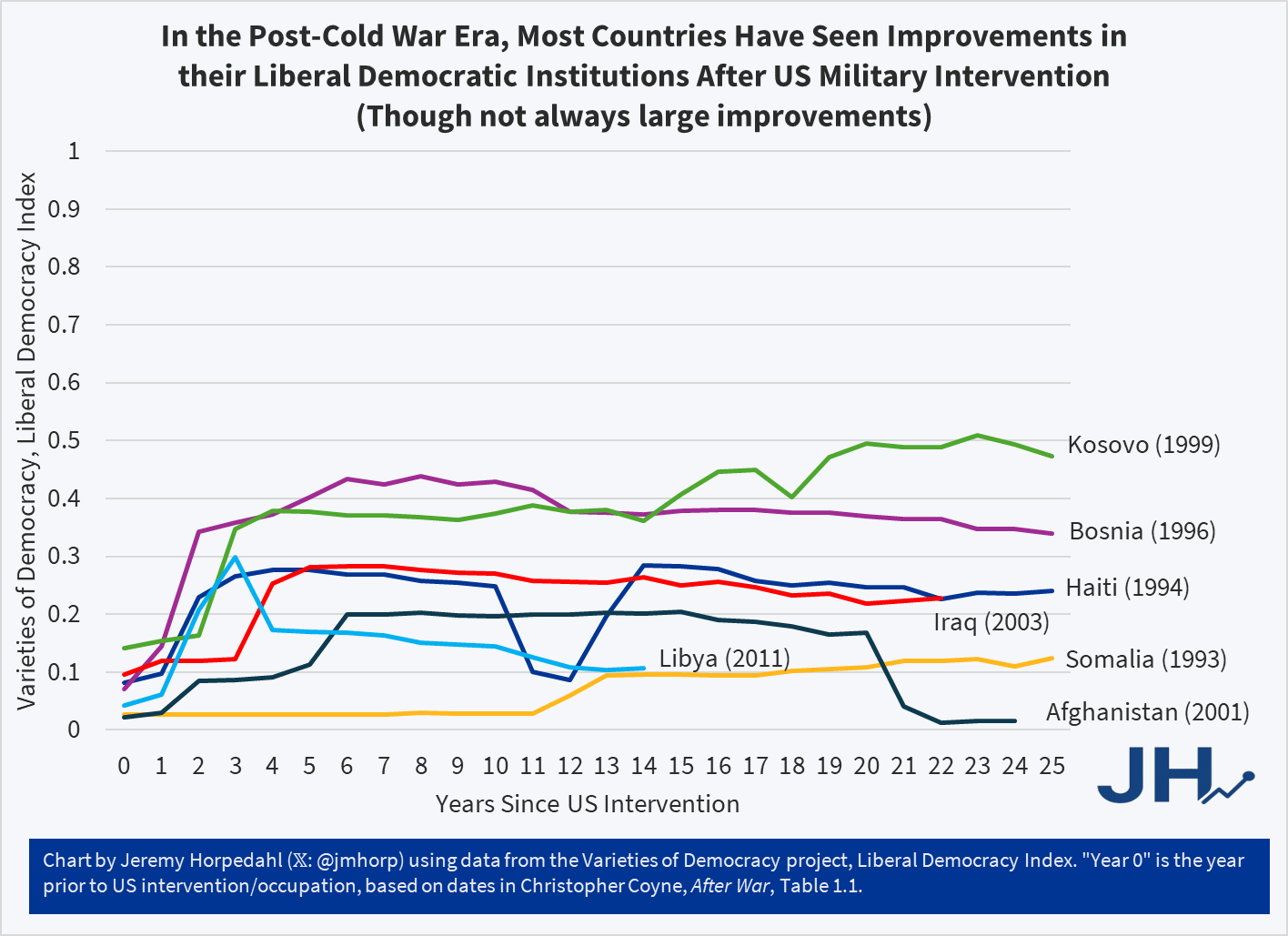

But what if we look at more recent interventions — post-Cold War — and look at direct military interventions by the US, rather than covert CIA operations or indirect funding of factions within a country. This is more in line with what might be happening in Venezuela right now (if regime change is ultimately what the US military pushes for). Using a list from Chris Coyne’s book After War (table 1.1) as a starting point for the relevant cases, and then using data from the V-Dem Liberal Democracy Index, we have seven cases since 1990 to examine (note: I have added Libya to Coyne’s list, which I believe is the only new addition of explicit military intervention since he created the list):

The first thing you might notice is that relevant to their starting position (pre-US military intervention), all except one of these countries saw improvements in their V-Dem Liberal Democracy Score after 25 years (or whatever the end point is for those more recent than 25 years). Some of the improvements — such as Libya, Somalia, and Iraq — are quite small, around 0.1 points on the 1-point scale. But other improvements — especially Kosovo and Bosnia — are quite large, around 0.3 points on the 1-point scale.

The one decline is Afghanistan, though you will note that during the occupation (which lasted a very, very long time, until 2021) their liberal democracy score did improve slightly, about as much as Iraq. I should also note that if we didn’t use my 25-year cut-off, Haiti would also have slipped back to roughly where they were in 1993, with a large decline happening since 2020.

For reference on this scale: the US scores 0.75 in 2024, the best scoring country is Denmark with 0.88, the World average is 0.37 (or 0.29 weighted by population), and the European average is 0.62 (or 0.56 weighted by population).

So while the improvements in Kosovo and Bosnia are impressive, they still fall below the average score in Europe. And those examples point to another problem with my simple analysis: we don’t have the counterfactual of what their score would be without US intervention. That kind of sophisticated analysis is what the above-mentioned Absher paper does (using synthetic control), but it’s more than I can do in a short blog post. Nonetheless, we should note that while we can’t say that US intervention caused these improvements, things didn’t get worse in most countries (as many critics of intervention assume always happens) — Afghanistan being the notable exception after the US ended the occupation.

Now that I’ve got the causation caveat out of the way, we should note a few more limitations of my analysis. First, perhaps the V-Dem Liberal Democracy Index isn’t the best one to use. Our World in Data has seven democratic measurement sets to choose from, and even from V-Dem there are others we could have used. I think Liberal Democracy best captures what we are usually talking about in terms of “does it work?” but you could use another measure. However, glancing through the other available measures, such as Polity, I don’t think the picture would be radically different with another measure of liberal democracy. 25 years is also somewhat arbitrary of a cut-off, though in Coyne’s book he uses 20 years, so I’m going beyond that.

Finally, I want to stress even more than on the causation point: none of these improvements mean the intervention passes a cost-benefit test. There was much destruction of lives and property in all of these cases, the use of US tax dollars, and some other harms to the US and international law (e.g., restrictions of civil liberties in the US from the War on Terror). I do not want to suggest that this means the interventions were worth the cost, merely that they did not fail on this one measure of improving democracy. It is also not a prediction that future interventions, such as in Venezuela, will succeed. Instead, I wrote this post because it goes against my priors (I would not have guessed improvements in 6/7 cases).