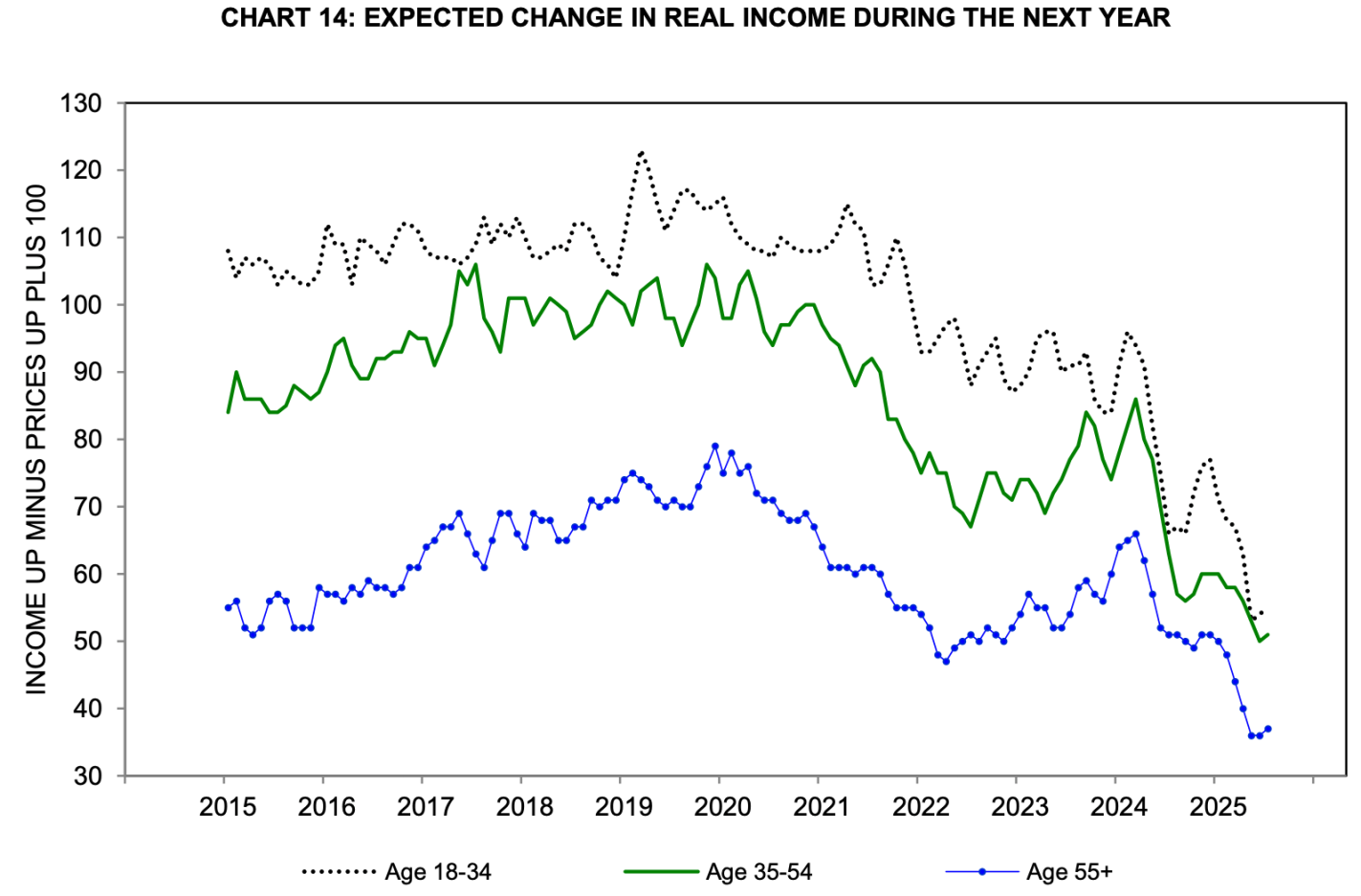

The young have always been more optimistic than the old, but this is no longer the case, at least according to the Michigan consumer sentiment survey:

But as Jeremy often points out here, young adults have actually been doing pretty well at building wealth. So why are they so gloomy?

Since I’ve now aged out of the young adult category, I’m obligated to start by wondering if kids these days are just whinier, and need to quit doomscrolling and toughen up. But if I try to see things their way, here’s what I can come up with for why their pessimism could be rational:

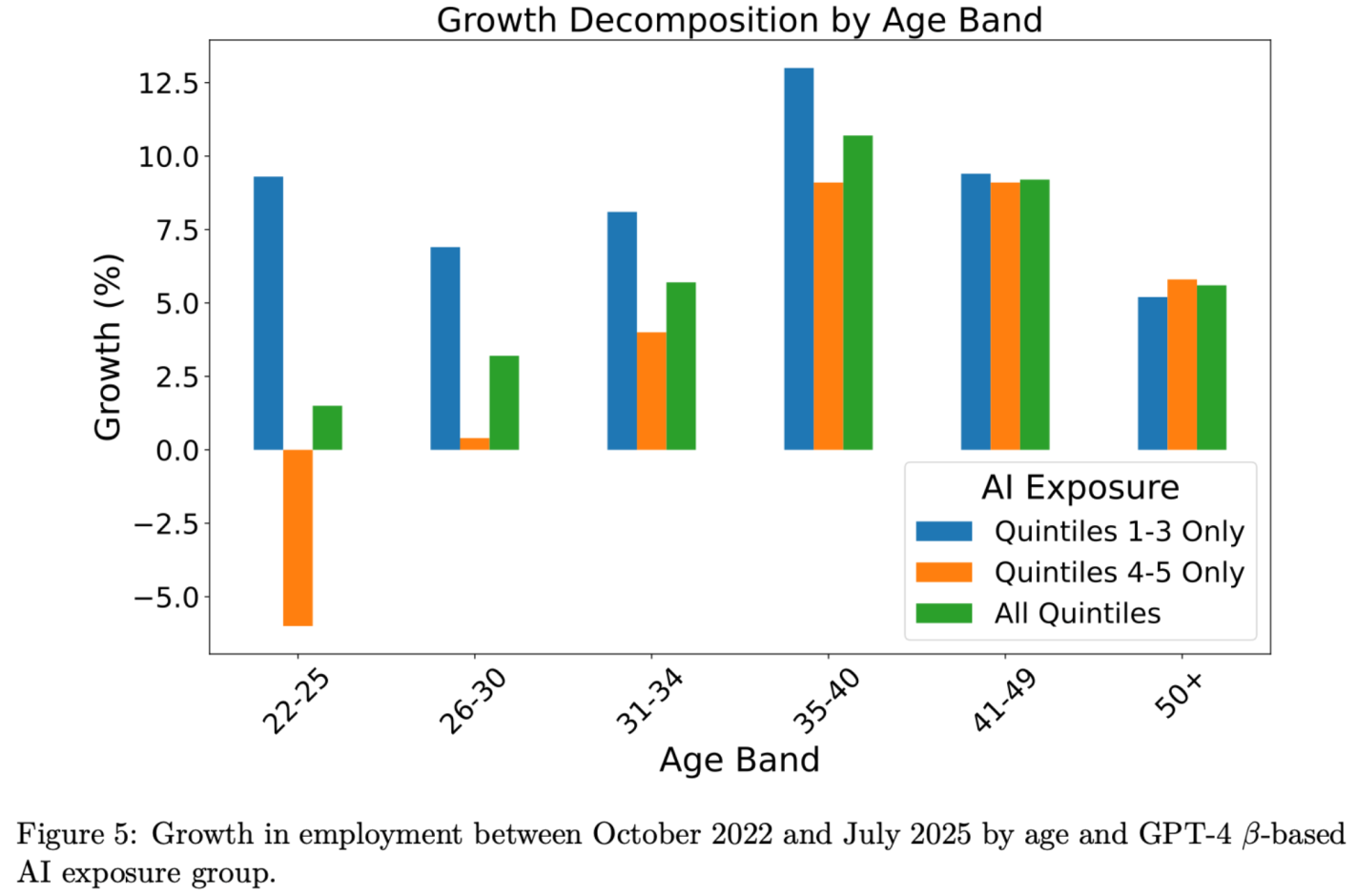

- It’s About The Future: Sure things have been fine, but that is about to change. The more farsighted youth know they will be the ones expected to pay back the big deficits the Federal government is running. They have student loans to pay today now that payments have fully resumed. I predicted after the 2022 student loan forgiveness that we would be back to all-time highs in student debt by 2028, but in fact we are there already. The youth unemployment rate is now 10.5%, up from 6.6% in April 2023, and could rise a lot more if AI really starts displacing jobs:

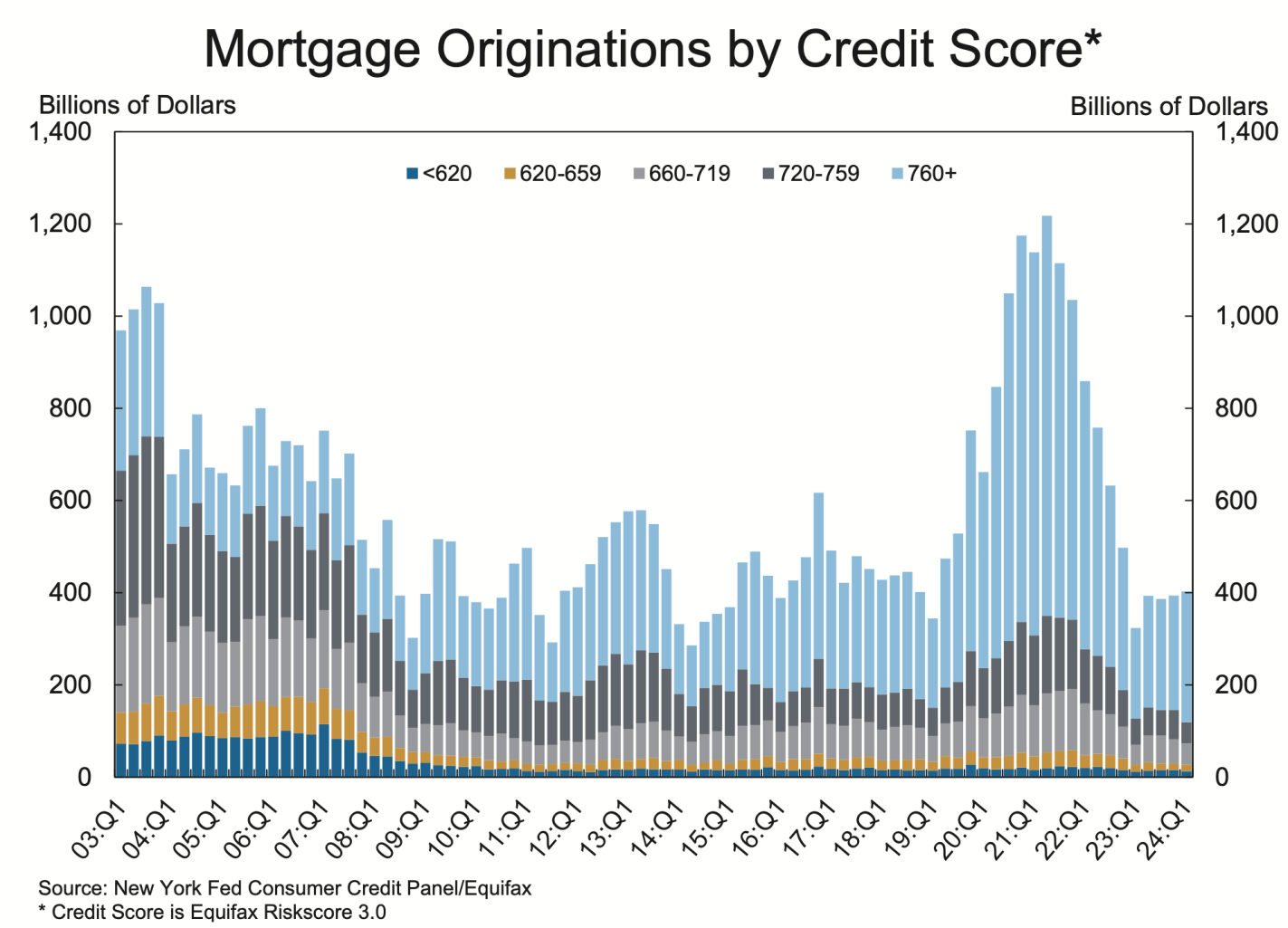

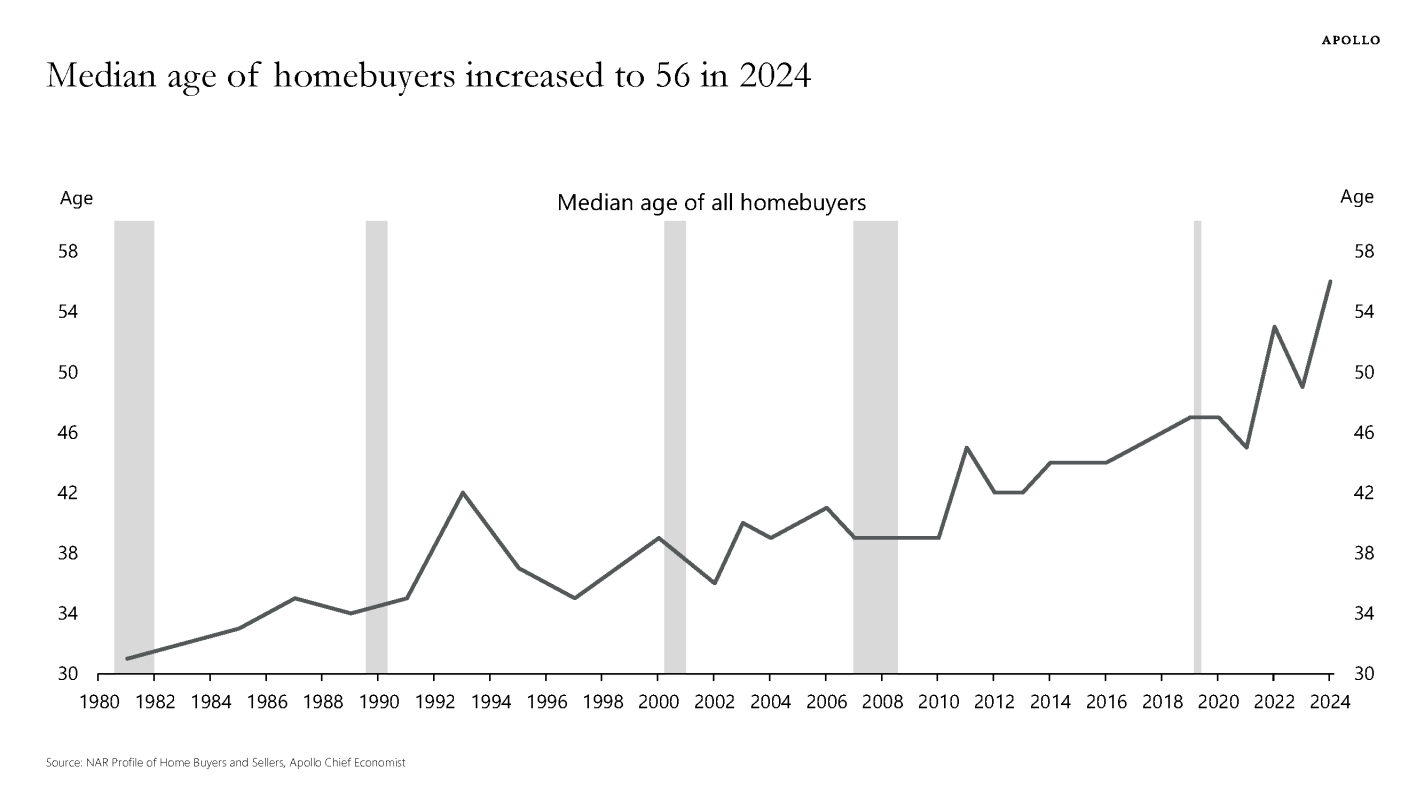

2. It’s About Housing: House prices are at all time highs (far above the prices during the 2000s “bubble”). Mortgage rates remain high, and to the extent that Fed rate cuts push them down, they will likely push prices higher, leaving homes hard to afford. High credit standards post-Dodd-Frank mean younger buyers in particular find it hard to get a mortgage; homeownership rates are falling while the average age of homeowners shoots upward. Most older people already own a house, while most young people want to buy but see that as increasingly out of reach.