For many people nowadays, investing in “stocks” means buying a fund like SPY or VOO which tracks the large cap S&P 500 index, or maybe QQQ or QQQM which track the tech-heavy NASDAQ 100 index. These types of funds are exchange-traded funds (ETFs), which very low annual fees (around 0.2% or so). These are so-called passive funds, which mechanically buy and sell stocks such that their holdings match what is in their respective indices. No extra judgment on stock picking is required.

An alternative is to pick stocks yourself, or to buy into a fund with active management, where humans (and their algorithms) try to buy stocks which will beat the passive indices, and try to avoid losing stocks. The active versus passive debate has been going on for decades. There will always be some active funds that outperform in any given year. These successes help keep the allure of active management alive. On average, though, the performance of active funds (before fees) is generally not much different than the passive funds. Thus, with their added fees, the active funds are net losers.

However, there are always cheerful fund managers with a story on how they have a plan to kill it this year, and there are investors willing to buy those stories. Sometimes these fund managers take financial advisors out for expensive lunches, and, behold, said advisors then recommend these actively managed funds to their clients. And so, there are plenty of active funds that still exist. New ones are minted every year, even as some older ones go out of business.

A problem with benchmarking against a cap-weighted fund like SPY or QQQ is that these passive indices are actually very effective. These work as closet momentum-rewarding funds: as the share price of, say, Microsoft goes up and up (presumably because of accelerating earnings), its representation among the biggest 500 companies (by stock capitalization) goes up. Thus, the better, growing companies automatically keep making bigger contributions to the indices, while fading companies sink to lower and lower per cent weighting. That works well to relentlessly home in on the relatively few stocks that account for the gains of the entire market, and to weed down all those other firms, most of which are net losers on stock price over time. This algorithm governing the cap weighted funds is tough for active management to beat.

Having stated these challenges, I’d like to compare performance of some actively-managed funds that have shown enhanced performance in recent years. The problem is, of course, we cannot know if this outperformance will continue. But hopefully looking at performance and discussing the underlying strategies of the funds may help investors decide if they would like to participate in any of them.

Two broad categories of stock funds are growth and value. Growth looks at how fast a firm is increasing revenues, earnings, etc. Most tech stocks command high share prices because of their growth prospects, rather than current earnings (although many of the current big tech leaders generate gobs of cash). Value looks at measures such as price/earnings and price/sales and price/book value, hoping to find undervalued firms whose price does not yet reflect the underlying value. Tech funds are generally under-represented in the value category.

Here we will look at five good actively-managed ETFs, and compare total returns (with dividends reinvested) to the S&P 500 fund SPY. They all claim to incorporate both growth and value into their stock picking. These five funds are:

SPGP – This is a supposed “growth at a reasonable price” fund, which seems to weight value more than growth. In top ten holdings, there is only one tech stock, a 2.7% weighting of Nvidia. There are four petroleum companies, and diverse smattering of other types of firms.

GARP – Another “growth at a reasonable price” (note “G.A.R.P.”) fund. This tilts heavily toward growth: seven of the top ten holdings are tech, with 5.43% Nvidia.

PVAL – As indicated in the name (Putnam Focused Large Cap Value), this is a value fund, but with some growth considerations – – The top ten are: Walmart (retail), Exxon Mobil (petro), Thermo Fisher Scientific, Citigroup, Bank of America (finance), Oracle (tech), UnitedHealth Group (healthcare), Coca-Cola, NXP Semiconductors, and PulteGroup (homebuilder).

MOAT – – “VanEck Morningstar Wide Moat” – This fund seeks to replicate the performance of the Morningstar® Wide Moat Focus Index, which in turn tries to identify a diverse group of U.S. large companies with wide “moats”, that give them sustainable advantages over competitors. Four measures are used to determine a corporation’s dominance: Intangible Assets (brands, patents, proprietary technologies); Switching Costs (inconvenient for the customer to find an alternative); Network Effect (when customers use one service, they adopt additional company services); Cost Advantage.

FFLC – This fund uses “fundamental analysis” and looks for companies that can take advantage of trends in “technological advances, product innovation, economic plans, demographics, social attitudes, and other factors”. An analysis of the fund’s holdings (heavy in big tech; 6% Nvidia) shows a strong focus on growth and momentum, with a moderate value weighting.

All these funds have plausible rationales for choosing the stocks they do. A big question is always: how much of a company’s promise is already reflected in its stock price? If everyone else has already figured out that, say, Microsoft will have high sustained earnings growth, then maybe the current share price is so high that it will not go up any faster than the broad market.

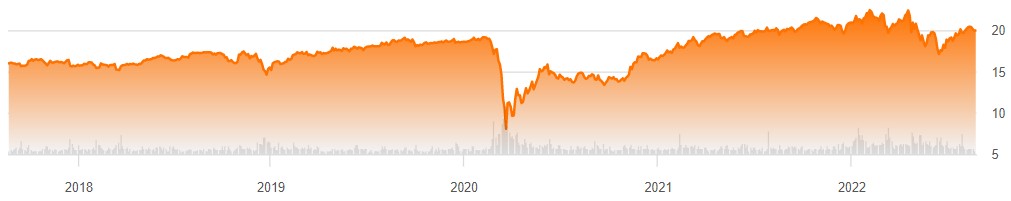

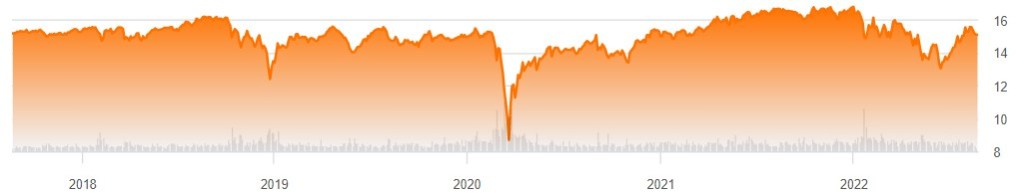

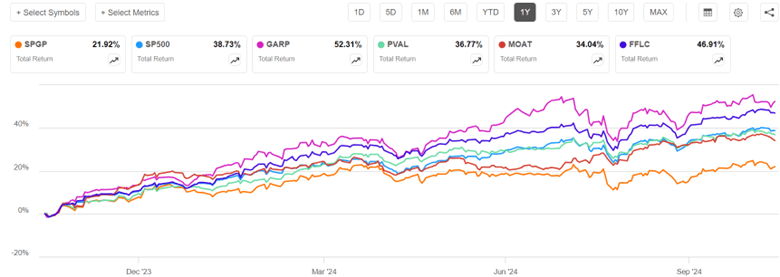

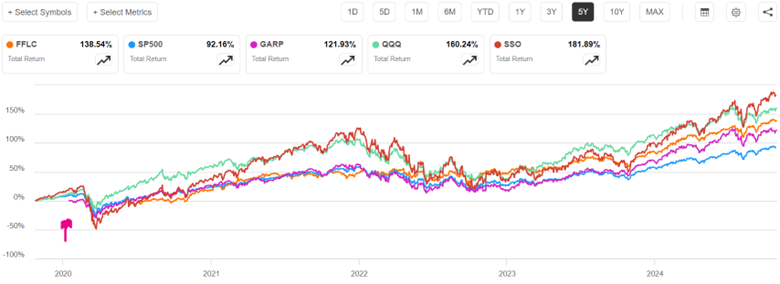

Now for the charts. I will discuss 1-year, 3-year, and 5-year charts, so we can see how the fund strategies worked in different market regimes. The one-year chart covers the raging bull market of the past twelve months, especially in AI-related tech/growth stocks. The 3-year chart encompasses a lengthy bear episode that occupied most of 2022, in reaction to the raising of interest rates to tamp down inflation. The 5-year chart includes the brief but sharp pandemic panic March-April 2020, sandwiched in a huge rise in internet-related big tech stocks 2019-2021.

One-Year Chart

Over the past one year, GARP (52% return) soared way above S&P 500 (blue line, 39%), but with high volatility, consistent with its heavy growth/tech exposure. FFLC steadily pulled ahead of SP500 over the past twelve months, racking up a 47% return. PVAL and MOAT finished close to SP500, while tech-poor SPGP flat-lined in the most recent six months and so got left far behind.

Three-Year Chart (End Oct 2021-end Oct 2024)

The defining features of the past three years were a roughly 21% bear market decline in S&P 500 during Jan-Oct 2022, followed by a strong recovery, which was interrupted by a moderate slump July-Oct 2023. FFLC and PVAL performed nearly identically for the first third of this time period (through early March, 2023). They dropped much less than SP500 in 2022, and so by early March, 2023 they were some 15% ahead of SP500. PVAL’s lead over SP500 shrank a bit over the next twelve months, and then widened March-July 2024, to give PVAL (43%) a 16% advantage over SP500 (27%) at the end of three years. FFLC just kept steadily widening its lead over SP500, ending with a 58% return over this three-year time period. MOAT and SPGP also fell less than SP500 in 2022, but fell more than PVAL and FFLC, and they did not keep pace with the tech-led surge in 2023-2024. In the end, MOAT finished essentially even with SPY, and SPGP finished lower (18%). Tech-heavy GARP crashed harder than SP500 in 2022, but more than made up for it with the 2024 tech-fest, finishing well above SP500 and tied with PVAL at 43%.

I won’t show the full five-year chart, since some of the funds did not start prior to that period. But I will make a few semi-quantitative comments. The five-year time period is a little kinder to SPGP – this fund showed a fairly consistent lead over SP500 in 2021 as well as 2022, and so got rave reviews then in the investing literature. It was only in the past six months that it performed so poorly.

FFLC got off to a rocky start, falling about 10% behind SP500 in 2020-2021, although its winning ways since then gave it the overall best 5-year performance. GARP and MOAT pretty much kept pace with SP500 Oct 2019-Oct 2021, so their five-year performance vs SP500 is about the same as for three-year (GARP soundly beat SP500, MOAT roughly tied).

One more chart (below), a five-year comparison of SP500 to FFLC (overall winner among the active funds discussed above) and GARP (tech-heavy) to QQQ (passive, tech-heavy, tracks NASDAQ 100 stocks) and SSO (its stock price moves up and down 2X the daily price movement of S&P500). GARP didn’t start operation till early 2020 (marked by red arrow on chart), to its curve should be shifted up to make a fair comparison with the others; with this correction, it would end up roughly tied with FFLC, with both these funds beating SP500 by about 33% (135% return vs 92%). But even these stellar active funds were soundly beaten by QQQ and even more by the passive 2X fund SSO. Holders of SSO, however, would have suffered heart-stopping drawdowns along the way (e.g. over 50% loss in market value in early 2020).

Readers can draw their own conclusions from this flyover of results. Just like you can fool people some of the time, any active fund may beat “the market” (e.g., S&P 500) some of the time. Some active funds seem to beat the market most of the time. But it is most unlikely that any given fund will beat it all of the time. The S&P 500 algorithm is actually pretty effective. It may behoove the investor to make their own judgement as to what market regime we are in or are about to be in, and to choose active funds which are more likely to thrive in that regime.

I am motivated to include some FFLC (for overall consistent good performance) and PVAL (for a bit of crash protection) in my holdings. But I recognize that their performance could deteriorate in the future, if their investing style no longer works in some new market regime. SPGP is a cautionary example, going from rock star in 2021-2022 to awful in 2024. Even FFLC had an unfavorable first year of operation. The tech giants that dominate QQQ continue to also dominate earnings growth, so QQQ may continue to outpace SP500.

As far as SSO, I earlier wrote on strategies for 2X returns using 2X funds or call options. If you think stocks are going to keep going up, it can make sense to hold these 2X funds. Many advisors, though, recommend against just buy and hold because of the enormous possible losses in a crash; too many investors panic and sell at a low price in that situation. I hold some QLD, which is a 2X QQQ fund, but only as a minor component of my portfolio. Also, if I can overcome fear in the moment, I plan to swap out of plain vanilla stock funds and into a 2X fund like SSO after the next big dip in the market, and then swap back out of SSO after the market recovers.

Disclaimer: Nothing here should be considered advice to buy or sell any security.