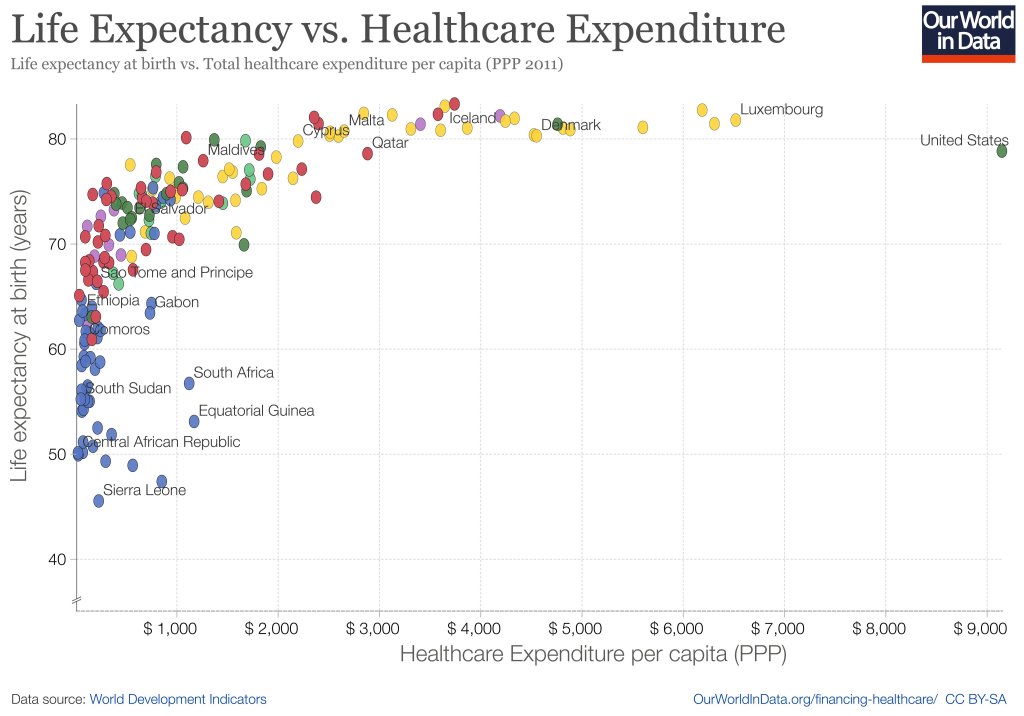

When you look across countries, it appears that the first $1000 per person per year spent on health buys a lot; spending beyond that buys a little, and eventually nothing. The US spends the most in the world on health care, but doesn’t appear to get much for it. A classic story of diminishing returns:

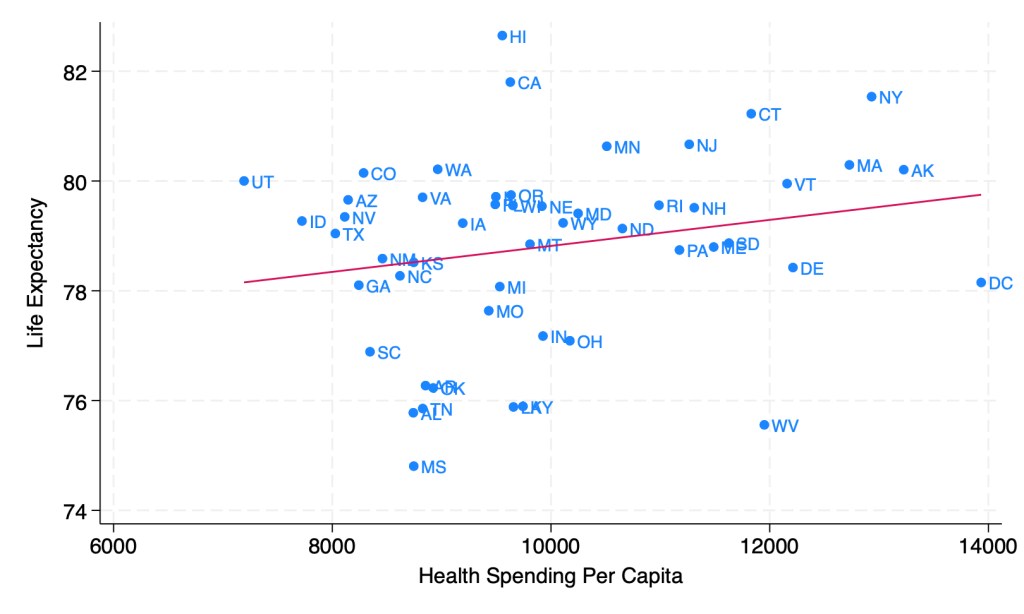

This might tempt you to go full Robin Hanson and say the US should spend dramatically less on health care. But when you look at the same measures across US states, it seems like health care spending helps after all:

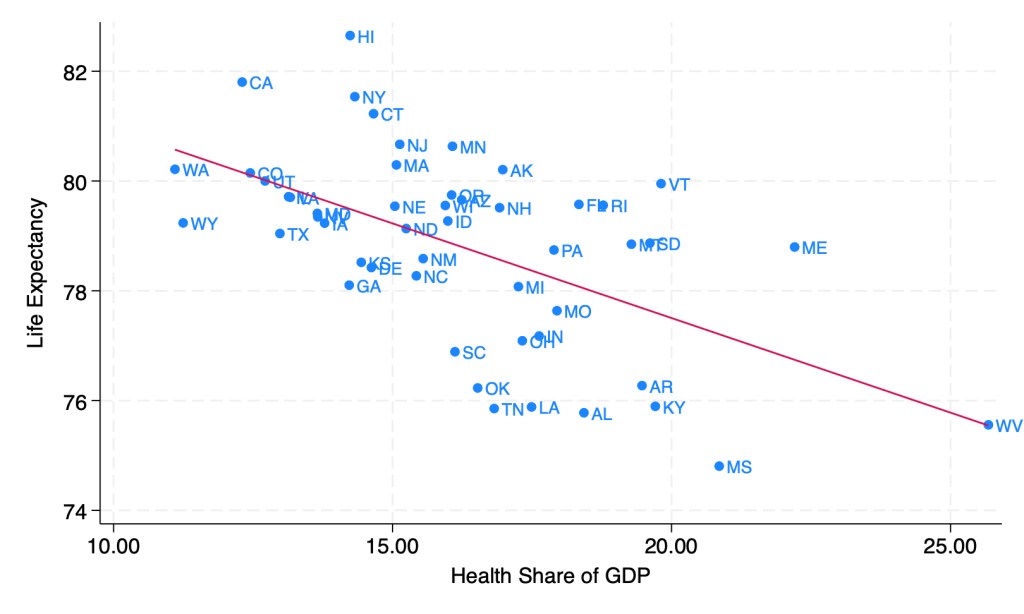

Last week though, I showed how health spending across states looks a lot different if we measure it as a share of GDP instead of in dollars per capita. When measured this way, the correlation of health spending and life expectancy turns sharply negative:

Does this mean states should be drastically cutting health care spending? Not necessarily; as we saw before, states spending more dollars per person on health is associated with longer lives. States having a high share of health spending does seem to be bad, but this is more because it means the rest of their economy is too small, rather than health care being too big. Having a larger GDP per capita doesn’t just mean people are materially better off, it also predicts longer life expectancy:

As you can see, higher GDP per capita predicts longer lives even more strongly than higher health spending per capita. Here’s what happens when we put them into a horse race in the same regression:

The effect of health spending goes negative and insignificant, while GDP per capita remains positive and strongly significant. The coefficient looks small because it is measured in dollars, but what it means is that a $10,000 increase in GDP per capita in a state is associated with 1.13 years more life expectancy.

My guess is that the correlation of GDP and life expectancy across states is real but mostly not caused by GDP itself; rather, various 3rd factors cause both. I think the lack of effect of health spending across states is real, between diminishing returns to spending and the fact that health is mostly not about health care. Perhaps Robin Hanson is right after all to suggest cutting medicine in half.