We seem to be somewhat exhausted by all the dire predictions around Covid, now that life has largely gotten back to the normal. Shops and theaters are open, and people are once more crowding aboard those floating petri dishes called cruise ships. The most vulnerable segments of the population have mainly been vaccinated, and each new strain of the disease seems less harmful. All the anti-vaxxers I know have had Covid at least once and hence have some level of immunity, or else they caved and got vaccinated after seeing a close friend or relative die back in the winter of 2021-22. One enduring benefit of Covid is much more availability to work from home.

One of the direst prognostications was that the world would suffer a more or less permanent step down in standards of living due to “long Covid.” According to this narrative, untold numbers of healthy young or middle-aged people would remain debilitated indefinitely due to the ongoing after-effects of a Covid infection: struck down in their prime, never to rise again.

A recent review of the field in Nature concluded, “The oncoming burden of long COVID faced by patients, health-care providers, governments and economies is so large as to be unfathomable”. Ouch. The federal government has provided $1.15 billion for research into the problem of long COVID and its mitigation.

Just the Facts

A couple of facts stand out: First, in many cases, scans of internal organs have shown changes in victims’ hearts and lungs and brains, following a severe Covid infection. Second, many people have reported symptoms such as weakness, fatigue and general malaise, impaired concentration and breathlessness, weeks after the primary symptoms of the disease have resolved.

How big a problem is this? I cannot, in the scope of a short blog post, adequately canvass all the data and literature. I will just cite a few numbers and charts, and let the professional data analysts dig into the fine points.

One meta-analysis found that a full “41.7% of COVID-19 survivors experienced at least one unresolved symptom and 14.1% were unable to return to work at 2-year after SARS-CoV-2 infection.” [That number seems much higher than my personal observations would suggest]. A CDC survey found that as of July 26-Aug 7, 2023, about 5.8 % of all Americans (which is 10.4% of Americans who ever had Covid) report experiencing some effects of long Covid, with 1.5% of all American adults experiencing significant activity limitations as result of long Covid. These numbers show a modest downward trend with time.

The chart below depicts the incidence of long Covid in England, again showing a modest downward trend in the latest year:

Weekly estimates of prevalence of COVID-19 and long COVID in England. Source.

Correlation versus Causation

So: we have many people experience severe symptoms from Covid, but most resolve within a few months at most. That leaves a small but nontrivial minority of Covid victims reporting problems long after that window. A significant question is whether Covid of itself caused those long-term symptoms, or just precipitated some problem that was bound to show up anyway.

I have read poignant anecdotes of perfectly healthy young people who suffer from brain fog two years later. But I have lived long enough to be wary of generalizing from poignant anecdotes. After all, the whole anti-vaccination movement has been fueled by poignant anecdotes of, say, perfectly normal two-year-olds going autistic shortly after getting their vaccine shots.

The 2023 metastudy referred to earlier found that long Covid sufferers tended to be older, and had pre-existing medical comorbidities. Similarly, we have known since 2020 that the cohorts most likely to die from Covid were older folks (such as me!), many of whom were bound to die anyway.

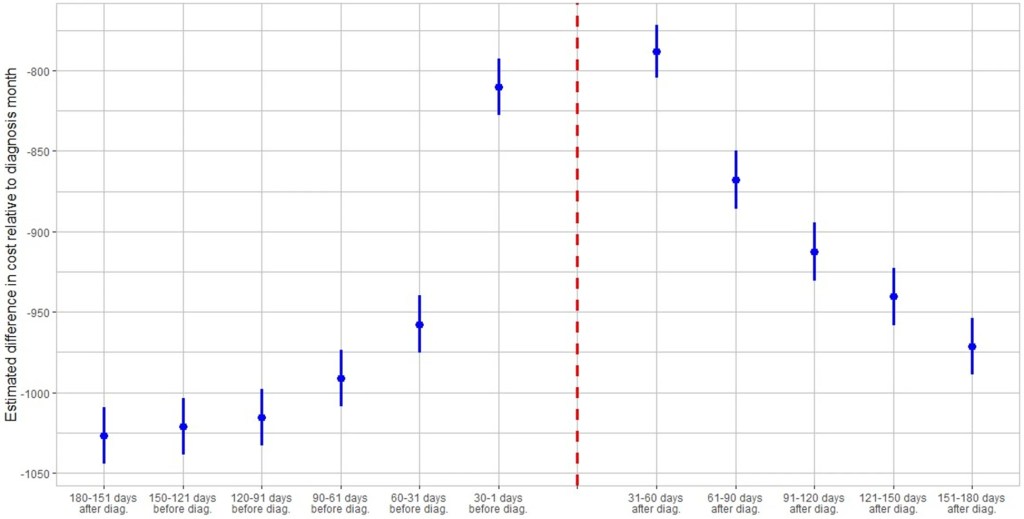

In this light, the data brought forth by James Baily in his recent article on this blog, Long Covid is Real in the Claims Data… But so is “Early Covid”?, is most interesting. He noted that on average people use more health care for at least 6 months post-Covid compared to their pre-Covid baseline, which is consistent with some measure of long Covid. However, those same individuals also spent significantly more on healthcare 1-2 months before their Covid diagnosis. This seems consistent with the notion that some of what gets blamed on Covid would have occurred sooner or later anyway.

A Nuanced View of Long Covid

An article in Slate by Jeff Wise has dug deeper into the data. He noted that the survey-based datasets that have been largely used to estimate the effects of long Covid tend to be biased: those who feel ongoing symptoms are more likely to complete the surveys, giving rise to some of the largish numbers I have shared above. Newer, better-controlled retrospective cohort studies tend to show much lower ongoing incidence of symptoms, especially compared to control groups who had not had Covid. The feared tidal wave of mass disabilities never arrived:

“The best available figures, then, suggest two things: first, that a significant number of patients do experience significant and potentially burdensome symptoms for several months after a SARS-CoV-2 infection, most of which resolve in less than a year; and second, that a very small percentage experience symptoms that last longer. ”

Further, “Another insight that emerges from the cohort studies into long COVID is that it is not so easy to prove causality between a particular infection and a symptom. Almost all the symptoms associated with long COVID can also be triggered by all sorts of things, from other viruses to even the basic reality of living through a pandemic.”

Finally:

It looks more as if people who complain of long COVID are suffering from a collection of different effects. “I think there’s quite a heterogeneous group of people all sailing under the one flag,” said Alan Carson, a neuropsychiatrist at the University of Edinburgh in Scotland. Some patients may be experiencing the lingering aftereffects that occur in the wake of many diseases; some patients with chronic comorbidities might be experiencing the onset of new symptoms or the continuation of old ones; others might be affected by the sorts of mood disorders and psychiatric symptoms you’d expect to find in a population undergoing the stress of a global pandemic.

Another Slate article from last month gently debunks alarmism stemming from a Nature Medicine study of U.S. veterans who showed increased susceptibility to disease even two years after contracting Covid.

There is often great difficulty in discerning the actual organic, biochemical basis for the reported symptoms. This makes it hard to come up with a pill or a shot that might adjust the body’s metabolic pathways in order to cure them. Thus, simply treating the symptoms as such may offer the best near-term relief. To that end, a team of French researchers had the audacity to propose that much of the fatigue and brain fog associated with long Covid may be largely in our heads. In an article in the Journal of Psychosomatic Research Why the hypothesis of psychological mechanisms in long COVID is worth considering , Lemogne, et al. noted strong links between a patient’s prior expectations of symptom severity and the actual reported outcomes. The intent of the researchers is not to belittle the reported distress of long Covid sufferers, but to point towards established therapeutic methods to help treat disorders with at least a partial psychosomatic basis:

Many potential psychological mechanisms of long COVID are modifiable factors that could thus be targeted by already validated therapeutic interventions. Beside the treatment of a comorbid psychiatric condition, which may be associated with fatigue, cognitive impairment or aberrant activation of the autonomous nervous system, therapeutic interventions may build on those used in the treatment of ‘functional somatic disorders’, defined as the presence of debilitating and persistent symptoms that are not fully explained by damage of the organs they point. These disorders are common after an acute medical event, particularly in women, and include psychological risk factors, such as anxiety, depression, and dysfunctional beliefs that can lead to deleterious, yet modifiable health behaviors. Addressing these factors in the management of long COVID may provide an opportunity for patient empowerment.

In sum: A significant number of those who contract COVID suffer ongoing symptoms for a number of months afterward. Over a billion dollars of research has been directed at the problem. The severity of these symptoms tends to decline with time, in the vast majority of cases resolving by twelve months. This leaves some individuals still suffering fatigue and brain fog over a year later. Studies are ongoing to discern the organic basis of these complaints, and the exact role that COVID may have played, in the light of the fact that complaints of enduring fatigue and brain fog were not uncommon before the pandemic. We hope that following the science will bring more relief here.

Circling back to our original interest in the economic impact of long COIVD, early studies indicated that a large fraction of the population might continue to be debilitated, to the point of being unable to work, with significant effects on the workforce and GDP. Actual data (e.g., on disability claims) indicate that these problems have not actually materialized.