I’ve always told my health economics students that Medicaid is both better and worse than all other insurance in the US for its enrollees.

Better, because its cost sharing is dramatically lower than typical private or Medicare plans. For instance, the maximum deductible for a Medicaid plan is $2.65. Not $2650 like you might see in a typical private plan, but two dollars and sixty five cents; and that is the maximum, many states simply set the deductible and copays to zero. Medicaid premiums are also typically set to zero. Medicaid is primarily taxpayer-financed insurance for those with low incomes, so it makes sense that it doesn’t charge its enrollees much.

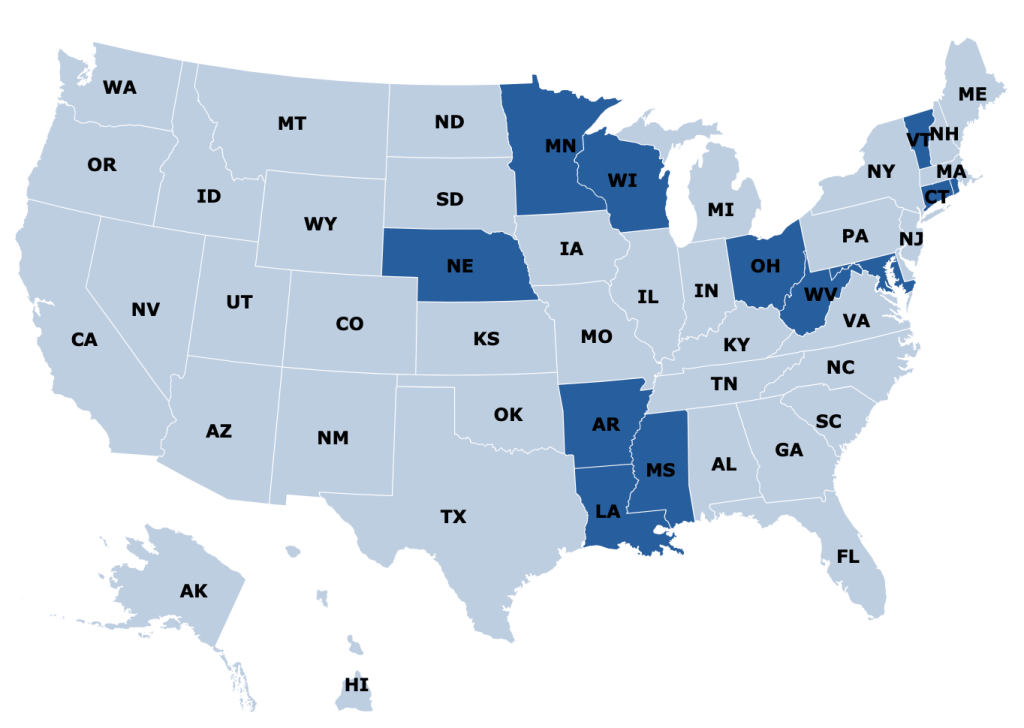

But Medicaid is the worst insurance for finding care, because many providers don’t accept it. One recent survey of physicians found that 74% accept Medicaid, compared to 88% accepting Medicare and 96% accepting private insurance. I always thought these low acceptance rates were due to the low prices that Medicaid pays to providers. These low reimbursement rates are indeed part of the problem, but a new paper in the Quarterly Journal of Economics, “A Denial a Day Keeps the Doctor Away”, shows that Medicaid is also just hard to work with:

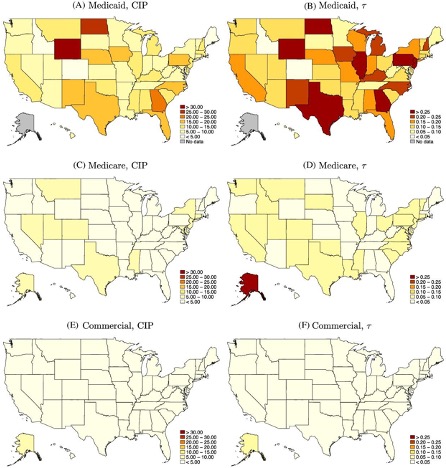

24% of Medicaid claims have payment denied for at least one service on doctors’ initial claim submission. Denials are much less frequent for Medicare (6.7%) and commercial insurance (4.1%)

Identifying off of physician movers and practices that span state boundaries, we find that physicians respond to billing problems by refusing to accept Medicaid patients in states with more severe billing hurdles. These hurdles are quantitatively just as important as payment rates for explaining variation in physicians’ willingness to treat Medicaid patients.

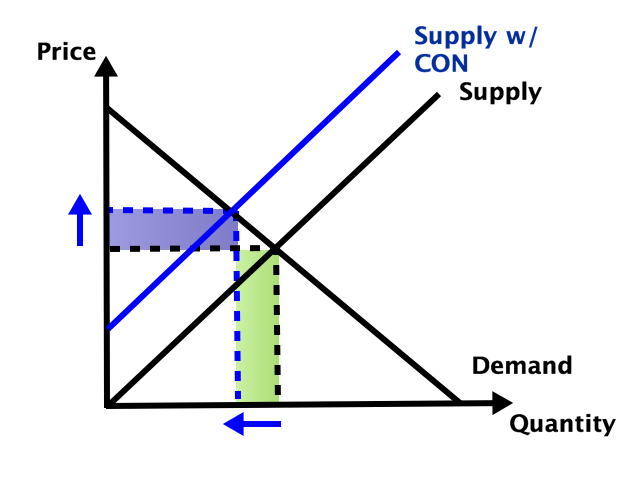

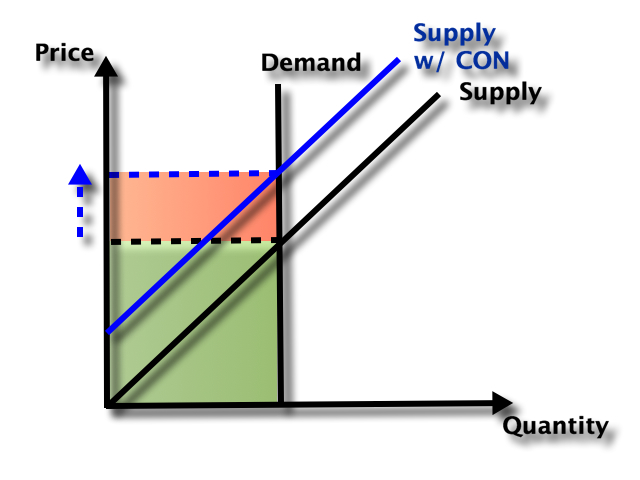

Of course, Medicaid is probably doing this for a reason- trying to save money (they are also trying to prevent fraud, but I have no reason to expect fraud attempts are any more common in Medicaid than other insurance, so I don’t think this can explain the 4-6x higher denial rate). This certainly wouldn’t be the only case where states tried to save money on Medicaid by introducing crazy rules hassling providers. You can of course argue that the state should simply spend more to benefit patients and providers, or spend less to benefit taxpayers. But the honest way to spend less is to officially cut provider payment rates or patient eligibility, rather than refusing to pay providers as advertised. In addition to being less honest, these administrative hassles also appear to be less efficient as a way to save money, probably because they cost providers time and annoyance as well as money:

We find that decreasing prices by 10%, while simultaneously reducing the denial probability by 20%, could hold Medicaid acceptance constant while saving an average of 10 per visit.

Medicaid is a joint state-federal program with enormous differences across states, and administrative hassle is no exception. For administrative hassle of providers, the worst states include Texas, Illinois, Pennsylvania, Georgia, North Dakota, and Wyoming: