I just found out I’ll be receiving a Course Buyout Grant from the Institute for Humane Studies. It will allow me to teach less next year in order to focus on my research on how Certificate of Need laws affect health care workers.

I’m happy about this because I think this research is valuable and time is my main constraint on doing it (especially doing it quickly enough to inform ongoing policy debates in several states). But I’m also happy because I finally got what I consider to be a “true” grant after many rejections.

I’ve received research funding many times before (e.g. Center for Open Science funding for replications), but it was always relatively small amounts that went directly to me. True grants tend to be larger and to be paid directly to the university. That’s the case with the course buyout grant, which essentially pays the university enough that they can hire someone else to teach my class.

I may have lost count but I’m pretty sure this was the 13th “true grant” I have applied for, and the 1st I will actually receive. Academics have to get used to rejection, since we need to publish and decent journals tend to reject 80%+ of the articles they receive. But for some reason I’ve found grants much harder even than that. From some combination of skill, luck, and targeting lower-tier journals than perhaps I could/should, my acceptance rate for journal articles is probably nearing 50%. I expected this to translate over to grants but it absolutely did not, they seem to be a much different ballgame, one I’m still figuring out.

I’d like to share some of those past misses, both to let junior people see the bumpy road behind success (like a CV of failures), and to try to extract lessons from an admittedly small sample. These proposals were not funded, and probably weren’t even close:

- Peterson Foundation US 2050

- MacArthur Foundation 100 & Change

- RI INBRE (2x)

- National Institute for Health Care Management (1x, waiting to hear but probably about to be 2x)

- Kauffman Knowledge Challenge

- Economic Security Project

- Emergent Ventures

- FTX Future Fund (sometimes rejection is a blessing in disguise)

- Smith Richardson Foundation

- AHRQ

What did these failures of mine all have in common? Me, of course. This is not just a truism; in most of these cases I was applying for major grants solo as an assistant professor without previous funding. The usual advice is to work your way up with smaller grants or, preferably, as the collaborator of a senior professor with lots of previous funding who knows how things work. I knew that would be smart but I’ve tended to be at institutions without senior people in similar fields; almost all my research has either been solo or coauthored with students or assistant professors. Even my PhD advisor was a brand-new assistant professor when we started working together. I had good reasons for ignoring the usual advice to work with well-known seniors, and it has mostly served me well, but grants seem to be the exception.

Twice, I think I did come close on grant proposals, and both times it involved help from seniors at other institutions who had lots of previous funding. At one foundation that funds a lot of social science, my senior coauthor and I got glowing external reviews, but the internal committee rejected us on the grounds that we could do the project without their funding. They were right in the sense that we did do project anyway with no funding; it got published and even won a best paper award. But with their funding we would have done it faster and better and they would have gotten credit for it.

I do think it is smart for funders to consider whether the research would happen anyway without them, or whether their funding really improves things. But I think it is rare for funders to actually do this, and taking this rejection as advice probably led me to more rejections. I tried to propose bigger, more ambitious projects that needed expensive data so it was clear that I really needed the funding; but for most funders this probably made things worse. I have since heard several times that people who get lots of funding from major funders like NIH tend to submit proposals for research they have essentially already finished; that is why their proposals can look so thorough, credible, and polished. They then use the funding to work on their next project (and next proposal) instead of what they said it was for. That seems sketchy to me, but it’s certainly ethical to turn the proposal dial back somewhat toward “obviously achievable for me” from “ambitious and expensive”, and that’s what I’ve done more recently.

The other time I came close was with an R03 proposal to the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. First I got a not-close rejection, as I mentioned in the big list, where my proposal was “not discussed”. But AHRQ allows resubmission. At the prompting of my (excellent) grants office, I got feedback on the proposal from two kind seniors at other schools who get lots of funding. I rewrote the proposal based on their comments plus the rejection comments (which were actually quite detailed despite it being “not discussed”) and resubmitted it. This went way better- the resubmission got discussed with an impact score of 30 and a percentile of 17. Lower scores are better for AHRQ/NIH so this was pretty good, good enough that it might have been funded in a normal year, but 2019 was a bad year for government funding (though through some weird quirk I never actually got rejected; 4 years later their system still says “pending council review”). Again, the key to getting close was getting detailed feedback from people who know what they are talking about.

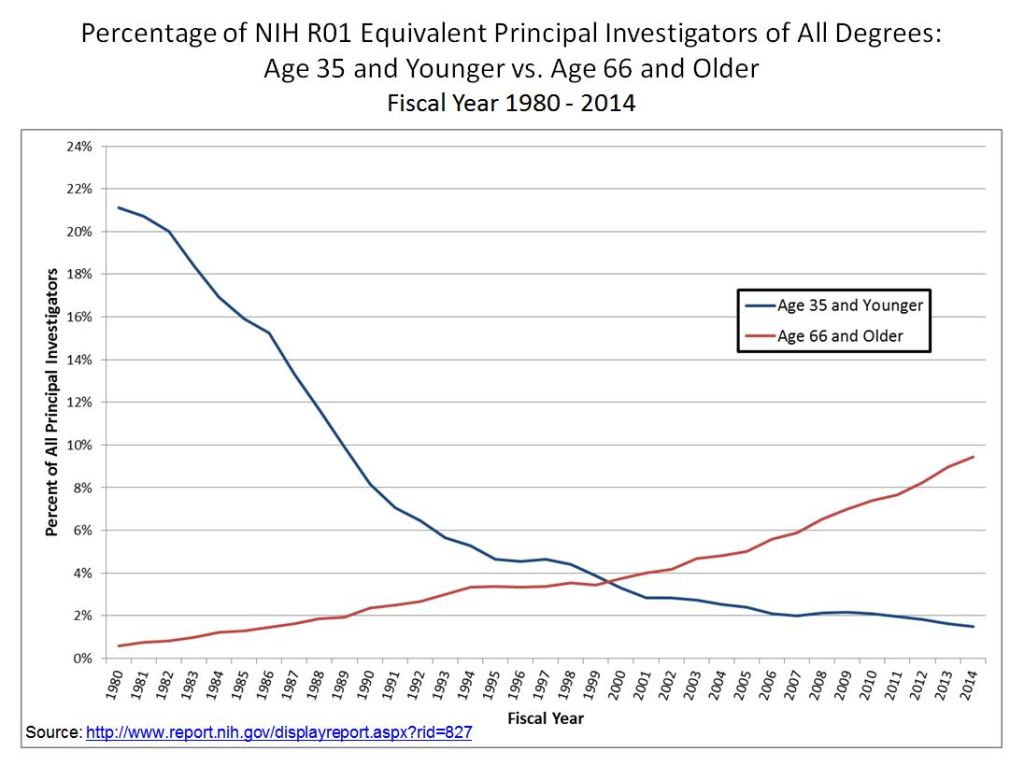

Of course, it also helps to get to know people at the funders and to become more senior yourself. It’s not surprising that my first major grant is coming from IHS given that I’ve been involved with them in all sorts of ways since going to a Liberty & Society seminar way back in 2009. Most funding goes to more senior people who have more connections, knowledge, and proven experience. This is extreme at perhaps the largest funder of research, the National Institutes of Health, where less than 2% of funded principal researchers are under age 36.

This may be the real secret for winning grants- just get older. My 12 rejections all came when I was younger than 36, while my first acceptance came less than a month after my 36th birthday.

In all seriousness, thanks to the Institute for Humane Studies, and I hope that a year from now I’ll be writing here about the great work that came out of this. For everyone with a growing pile of rejections, maybe the 13th time will be the charm for you too.