The Republicans hold a majority in both chambers of congress and they are the party of the president. They want to use that opportunity to pass substantial legislation that addresses their priorities. Hence, the One, Big, Beautiful Bill (OBBB). But, just like the Democratic party, Republican congressmen are a coalition with various and sometimes divergent policy agendas. There are ‘Trump’ Republicans, who want tariffs, executive orders, and deportations. There are more liberal members who want more free markets. You can also find the odd ‘crypto bro’, blue-state representatives, and deficit hawks. Given the slim majority in the House of Representatives, they all have to get something out of the legislation. Put them together, and what have you got?* You get a signature piece of legislation that no one is happy about but everyone touts.

One example of such compromise is the State and Local Tax federal income tax deduction, or SALT deduction. The idea behind it is that income shouldn’t be taxed twice. If you pay a part of your income to your state government in the form of taxes, then the argument goes that you shouldn’t be taxed on that part of your income because you never actually saw it in your bank account. The state took it and effectively lowered your income. The state and local taxes get deducted from the taxable income that you report to the federal government. The reasoning is that you shouldn’t need to pay taxes on your taxes.

Paying taxes on your taxes sounds bad. And plenty of people don’t like one tax, much less two. The Tax Foundation has done a lot of good work to cut through the chaff and has published many pieces on the SALT deduction over the years.**

Cut and Dry SALT Deduction Facts:

- It’s a tax cut

- It reduces federal tax revenue

- It adds tax code complication

- It is used by people who itemize rather than take the standard income tax deduction

- Prior to the 2017 Tax & Jobs Act, there was no limit on the SALT deduction. After, the limit was $10k.

- The current OBBB increases the SALT deduction.

Those are the basics. Everything else is analysis. The Grover Norquist Republicans never see a tax cut that looks bad, so they’d like to see the SALT limit raised or disappear. Tax think tanks that like simplicity don’t like the SALT deduction because it adds complication. Plenty of others say they don’t like complication, but often change their mind when it comes to the details (much like cutting government waste). Think tanks tend to be a bit lonely on this point.

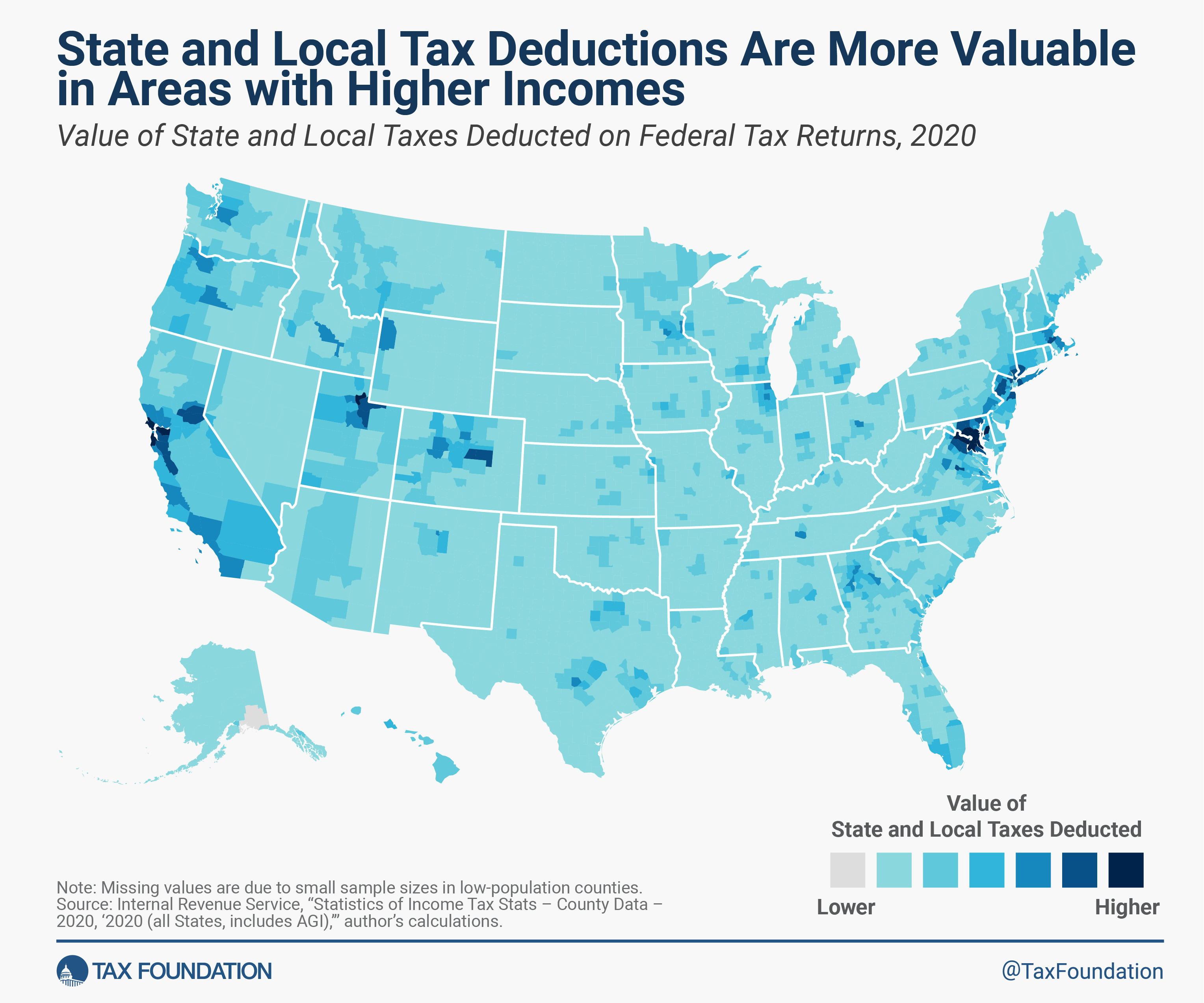

People mostly care about the SALT deduction due to the distributional effects. Who ends up benefiting from the deduction? The short answer is people who 1) itemize & 2) have heavy state and local tax bills. Who is that? Rich people of course! They have high incomes and lots of wealth and real estate – on which they pay taxes. But not all rich people pay loads of state taxes. So the SALT deduction is a tax cut that primarily benefits rich people who live in high tax districts. Where’s that? See the below.

Continue reading

Continue reading