And I twisted it wrong just to make it right

Had to leave myself behind

And I’ve been flying high all night

So come pick me up, I’ve landed-Fed Chair Ben Folds on the Covid inflation

The Fed has now almost landed the plane, bringing us down from 9% inflation during the Covid era to something approaching their 2% target today. But it is not yet clear how hard the landing will be. Back in March I thought recurrent inflation was still the big risk; now I see the risk of inflation and recession as balanced. This is because inflation risks are slightly down, while recession risk is up.

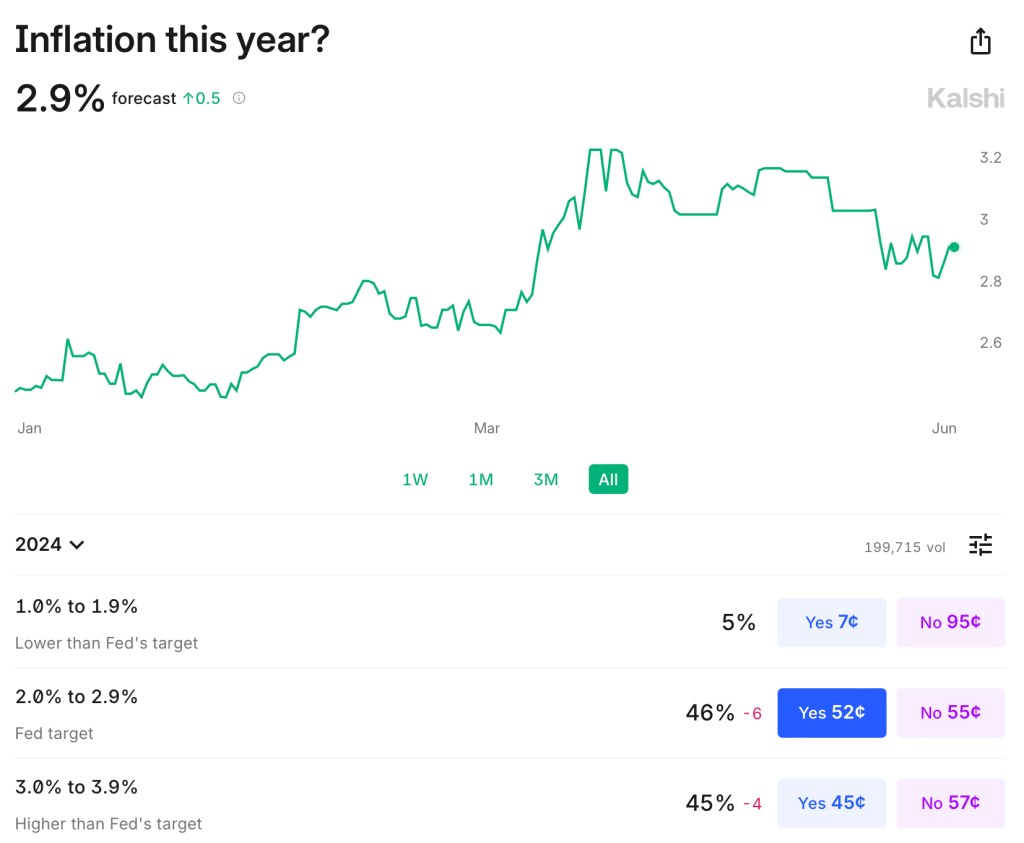

Inflation remains somewhat above target: over the last year it was 3.3% using CPI, 2.7% by PCE, and 2.8% by core PCE. It is predicted to stay slightly above target: Kalshi estimates CPI will finish the year up 2.9%; the TIPS spread implies 2.2% average inflation over the next 5 years; the Fed’s own projections say that PCE will finish the year up 2.6%, not falling to 2.0% until 2026. The labels on Kalshi imply that markets are starting to think the Fed’s real target isn’t 2.0%, but instead 2.0-2.9%:

The Fed’s own projections suggest this to be the somewhat the case- they plan to start cutting over a year before they expect inflation to hit 2.0%, though they still expect a long run rate of 2.0%. In short, I think there is a strong “risk” that inflation stays a bit elevated the next year or two, but the risk that it goes back over 4% is low and falling. M2 is basically flat over the last year, though still above the pre-Covid trend. PPI is also flat. The further we get from the big price hikes of ’21-’22 with no more signs of acceleration, the better.

But I would no longer say the labor market is “quite tight”. Payrolls remain strong but unemployment is up to 4.0%. This is still low in absolute terms, but it’s the highest since January 2022, and the increase is close to triggering the Sahm rule (which would predict a recession). Prime-age EPOP remains strong though. The yield curve remains inverted, which is supposed to predict recessions, but it has been inverted for so long now without one that the rule may no longer hold.

Looking through this data I think the Fed is close to on target, though if I had to pick I’d say the bigger risk is still that things are too hot/inflationary given the state of fiscal policy. But things are getting close enough to balanced that it will be easy for anyone to find data to argue for the side that they prefer based on their temperament or politics.

To me the big wild card is the stock market. The S&P500 is up 25% over the past year, driven by the AI boom, and to some extent it pulls the economy along with it. The Conference Board’s leading economic indicators are negative but improving overall this year; recently their financial indicators are flat while non-financial indicators are worsening.

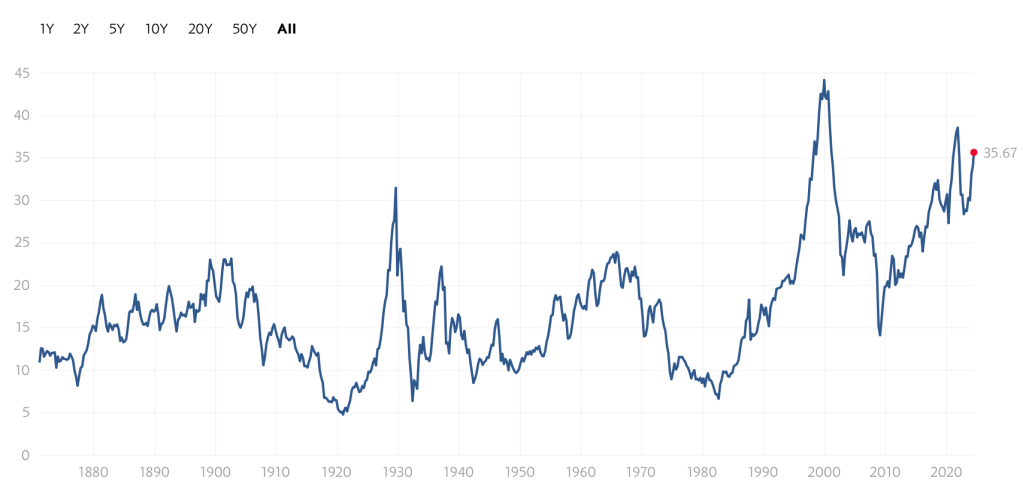

Overall things remind me a lot of the late ’90s: the real economy running a bit hot with inflation around 3% and unemployment around 4%; the Fed Funds rate around 5%; and a booming stock market driven by new computing technologies. Naturally I wonder if things will end the same way: irrational exuberance in the stock market giving way to a tech-driven stock market crash, which in turn pushes the real economy into a mild recession.

Of course there is no reason this AI boom has to end the same way as the late-90’s internet boom/bubble. There are certainly differences: the Federal government is running a big deficit instead of a surplus; there are barely a tenth as many companies doing IPOs; many unprofitable tech stocks already got shaken out in 2022, while the big AI stocks are soaring on real profits today, not just expectations. Still, to the extent that there are any rules in predicting stock crashes, the signs are worrying. Today’s Shiller CAPE is below only the internet and Covid meme-stock bubble peaks:

Again, this doesn’t mean that stocks have to crash, or especially that they have to do it soon; the CAPE reached current levels in early 1998, but then stocks kept booming for almost two years. I’m not short the market. But the macro risk it poses is real.