The Ukraine is as of this writing holding its ground and cities against the invading Russian army. There are a host of reasons, from incredible Ukrainian bravery, unmatched global sanctions clamping down on the Russian economy, to tactical and military failure on the part of Russia. There is nothing I can contribute beyond the linked sources or the constant flow of information coming out in real time. What I would like to add is one bit of broad economic context.

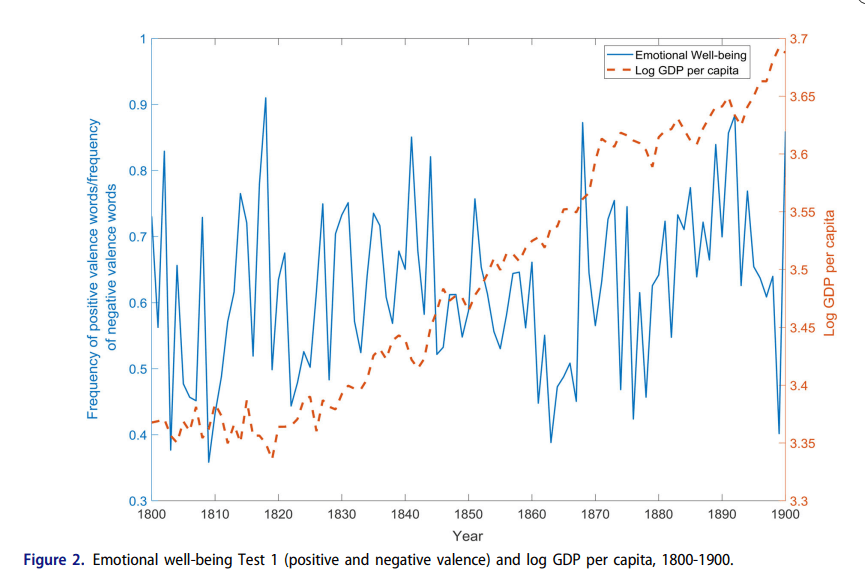

Baumol’s famous “cost disease” idea works like this: as a society gets richer the opportunity cost of everyone’s time increases. This makes certain services, like getting a haircut, more expensive because there is no substitute for a person’s time, no technology to increase labor efficiency, when it comes to cutting hair. Economists never stop speaking of the opportunity cost of time, but I sometimes think we undersell the importance of the concept. Lives are finite, time is the only thing that matters. To say that the opportunity cost of time has increased is to say that lives have been made better. Baumol’s cost disease restated: Anything that improves a person’s life makes claims on their time more dear.

The same logic applies to risk and to armies. Military technology continues to advance, but there as yet remains no substitute for soldiers, particularly if you want to occupy territory (there are plenty of superior substitutes if you just want to take lives and scorch the earth, but thats a different story). While the “labor productivity” of soldiers as occupying forces has remained relatively stagnant, the lives of the soldiers themselves has improved with everyone else’s. As their lives improve, the bar for what they are willing to risk their lives (and their conscience) for gets higher. For Ukrainians defending their homes and families from invaders, the risk is more than worth it and they are awing the world with their bravery everyday. Russian soldiers, on the other hand, are surrendering, scrolling Tinder, and abandoning tanks.

When historians point to generals making the mistake of fighting the “previous war”, they are usually referring to the obsolescence of tactics by new military technology. What I would like to consider is the possibility of Putin trying to fight a war with the previous soldiers. The last time the Russian army marched into a country prepared to offer significant resistance was the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan (Crimea, to my understanding, was never in a position to offer significant miltary resistance). Russian soldiers and their families today have very different lives. Only a quarter are conscripts, and none are facing a life without options outside of the army. The state is not the sole means of earning a living. The Russian market may be fractured and corrupted by a kleptocratic regime, but it’s still a market, one which has led to tremendous improvements in the quality of life enjoyed by citizens. These aren’t men and women enlisted into a religious or philosophical crusade, let alone ordinary men and women fighting to keep their homeland. Soldiers have lives they don’t just hold dear for the sake of survival – they have lives in the modern world they actively enjoy.

There have been no shortage of pundits who, in the form of cliched memes and cosplay masculinity, have speculated that nations of the developed world would not sufficiently come to the aid the Ukraine, or any country invaded by a foreign power, for the simple reason that we have, in our modern decadence, grown soft. What they consistently fail to appreciate is that this is a great outcome. People holding their lives with greater value is the very definition of progress. What is most perplexing, however, is why this idea of softness born of wealth is not applicable to Russians. (As for the theory that the Ukraine would fold overnight because it doesn’t make enough babies, that theory looks less viable, even if Russia achieves any of their goals.)

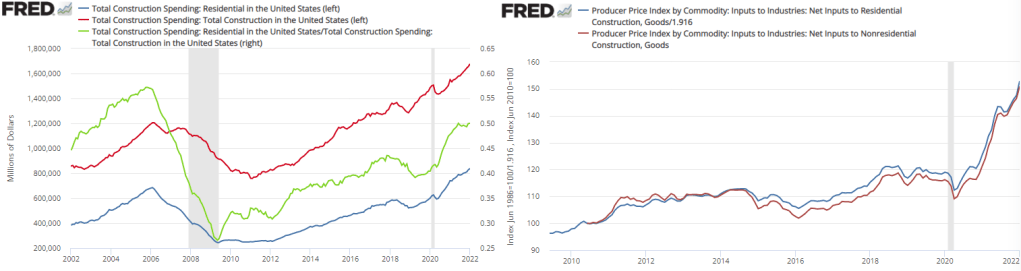

Working down the supply chain

Now, let’s be clear: soldiers are soldiers, and they are still more likely than not to obey orders and carry out their duties, if nothing else then out of a sense of obligation to one another. The opportunity cost effects of improved private lives are no doubt dampened. But armies depend on a lot more than just soldiers.

Russia remains, relative to the West, a poorer country in terms of GDP per capita, but nonetheless a modern economy where individuals enjoy the luxuries of a developed economy: mobile phones, heat in the winter, food security, transportation, etc. History is filled with stories of wars won and lost because of lack for boots, gasoline, and coats. In the Soviet Union, the army may have been underprovisioned relative to their counterparts from wealthier market economies, but they weren’t beholden to the rules of a market economy. Exclusion from a global system of payments wouldn’t be able to immediately choke off resources. Even if the soldiers marching are entirely severed from their lives in the private market, the supply chains they depend on are not, and the civilians in that supply chain expect to get paid.

Did Putin expect that supplies would arrive while the Ruble plummeted? Did he expect middlemen to incur losses as the entire economy was frozen by global sanctions? Did he expect reliable logistical support from soldiers and civilians while their spouses lined up at ATMs during bank runs? You know what? Maybe he did. Or at least, maybe he thought that the Ukraine would capitulate before sanctions could become salient to the supplying of his army. I have no idea. What I want us to consider is that modern armies depend on more than soldiers to function. Without a monopoly on means for supporting a family or an omnipresent threat of the Gulag, armies depend on citizens who can look at the physical and economic risk they are taking on, and coming to the conclusion that “this is worth it.” I have a hard time believing any Russian citizen, wage earner or oligarch, is looking at what is already an economy-enveloping sinkhole borne of greed for historical infamy, and thinking this is worth it for anyone but Putin himself.

This context of war in a time of better lives places economic sanctions as a geopolitical tool in a new light. Most countries cannot hope to put together an irresistible military force without the resources of a modern developed economy. A modern developed economy will invariably lead to wealthier citizens with a greater opportunity cost of time and risking their lives. The military will, in turn, become more dependent on private citizens to provision their armies. Sanctions in this new world don’t just punish citizens and encourage some form of open revolt, they actually choke off the military from the economies they remain entirely coupled to and dependent on.

If Putin is repelled, it will more than anything be because of the bravery of 44 million Ukrainians who stood their ground and protected their homes. But the military lesson, the historical lesson, may very well be that men and women with good lives make for poor invaders. The best, most peaceful future might just be one where we all have too much too lose.

Brief Addenum: How this “cost disease” effect would impact the probability of a nuclear strike is complex and in no way clear to me. On the one hand, if Putin believes that he has no possibility of victory without a credible threat of a strike, then it raises the possibility of war, if only through greater chance of error admidst readiness. On the other hand, it’s not like there are no middlemen between Putin and “the button.” Each link in that chain may be more likely to be insubordinate if they view their modern life as too great a sacrifice. I just don’t know.