As 2023 winds to a close, you’ll find lots of “year-end” lists. What would a year-end list for the US labor market look like?

Last week I put together some data on the state of the US economy and compared it to 4 years ago. On many measures, sometimes to the first decimal place, the US economy is performing as well as it did in late 2019 before the pandemic.

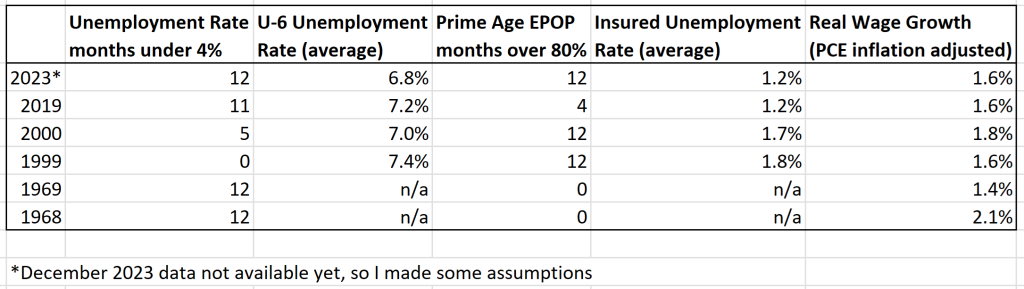

Today I’ll go into more detail on several measures of the labor force, but I won’t only compare it to 2019. I’ll compare it to all available data. And the sum total of the data suggests the 2023 was one of the best years for the US labor market on record. Note: December 2023 data isn’t available until January 5th, so I’m jumping the gun a little bit. I’m going to assume December looks much like November. We can revisit in 2 weeks if that was wrong.

The Unemployment Rate has been under 4% for the entire year. The last time this happened (date goes back to 1948) was 1969, though 2022 and 2019 were both very close (just one month at 4%). In fact, the entire period from 1965-1969 was 4% or less, though following January 1970 there wasn’t single month under 4% under the year 2000!

Like GDP, the Unemployment Rate is one of the broadest and most widely used macro measures we have, but they are also often criticized for their shortcomings, as I wrote in an April 2023 post.

With that in mind, let’s look to some other measures of the labor market.

First, perhaps the definition of “unemployed” is too narrow. BLS publishes several broader measures of labor force utilization, and the broadest is known as the U-6 rate. This rate includes people marginally attached to the labor force, as well as those that are “underemployed” (such as working part-time but prefer full-time employment. While the data only goes back to 1994, the average for 2023 so far is the lowest on record at 6.8%. It’s just a hair below 2022, as well as the very good labor market of 2000.

Another concern with the unemployment rate is that it could be artificially low if people are dropping out of the labor force. The employment-population ratio is one way to overcome this deficiency, and the so-called Prime Age Employment-Population Ratio is probably the best measure, which uses the population age 25-54. Prime Age EPOP has been above 80% for all of 2023, which only happened in the late 1990s and 2000 (all of the years 1997-2000). This data goes back to 1948, and it was much lower in late 1960s (under 70%) since the Quiet Revolution of women entering the paid labor force as not yet complete.

If you think that 25-54 is not the right age group since many under 30 are still in school, we can use a different age group but it doesn’t matter much. Using ages 35-44 (sorry no FRED link, but you can extract it here), the EPOP averaged 81.5% so far in 2023, which is only beat by the period 1997-2001 (data goes back to 1948).

What about the number of people on unemployment insurance? The Insured Unemployment Rate tells us the number of people on UI benefits as a percent of those covered by the UI system, and it has averaged 1.2% in 2023 so far. With data going back to 1971, this is almost the lowest ever, tied with 2018 and 2019, a touch higher than 2022 (1.1%), but also lower than the late 1990s (it was 1.7% or higher).

A measure of how “tight” labor markets are is the number of unemployed people per job opening. While the job openings data only goes back to 2001, the average for 2023 so far is the second lowest ever, only beat by 2022. We should be especially cautious about judging this measure right now, since it is only available through October 2023 and it is not seasonally adjusted. Nonetheless, this measure is clearly below the pre-pandemic years (which were also quite low!).

Given all of these good measures of the labor market, we might expect that one that people care about a lot, especially right now in this time of high inflation, would be doing better: real wage growth. But it’s probably doing better than you expect. After growth of exactly 0% in 2022 (PCE inflation adjusted), real wages have grown 1.6% in the past 12 months (through November 2023, it will probably be slightly better with December data).

That’s nowhere near the best ever, with 16 of the last 59 years being better, but I think we can still count it as somewhat impressive. Here are the years that rank better: 2020, 2008, 1972, 1997, 1971, 1998, 1967, 1976, 2015, 1968, 2001, 2006, 1965, 2000, 2018, and 1999. Some of these are anomalies because they are recession years, and thus the average wage data doesn’t tell us much (as low-wage workers might be dropping out of the average). Ignoring recession years, mostly here you have a few years from other good labor market periods we have seen come up several times: the late 1960s and late 1990s/2000. But we are basically already back to the pre-pandemic average, with 2023 being similar to 2018 and 2019.

So on real wage growth 2023 doesn’t stand out as stellar, but wage growth has been creeping up throughout the year, and unless 2024 sees a breakdown in labor market conditions I suspect it will be much higher on that list of the past 60 years.

Putting this all together, it seems pretty clear that 2023 is among the best labor market years ever. It is either near or beats most of the measures for the late 1960s and late 1990s. You can make a case that, say, 1969 or 1999 were the best years ever, but for young people (under 40) in the labor market, 2023 has been the best labor market of their working lifetime.

Here’s a table summing up the data for the possible Best Labor Market Years Ever (at least going back to the 1960s):

Let’s hope it continues into 2024.

3 thoughts on “2023: Great Labor Market, or Greatest Labor Market?”