Many people have nostalgia for nominal prices of the past. I’ve written about this topic in various contexts before, but the primary error in doing this is that you must also look at nominal wages from the past. Prices in isolation give us little context of how affordable they were.

One area with a lot of nostalgia is food prices of the past, specifically grocery prices (I’ve also written about fast food prices). While I have addressed grocery price inflation since 2021 in another post (it’s bad, but probably not as bad as social media leads you to believe), there is another version of grocery price nostalgia that goes back even further. For example, this image shows up on social media frequently with nostalgia for 1980 prices:

(Note that the image also mentions housing prices, but the clear focus of the image is on groceries. I won’t dig into housing in this post, but it’s something I have written a lot about before, and I would recommend you start with this post on housing prices from February 2024. But she sure looks happy! As models often do in promotional photos.)

Could you buy all those groceries for $20 in 1980? And how should we think about comparing that to grocery prices today?

One approach to grocery affordability is to look at how much a family spends as a share of their budget on food and other items. In the past I’ve used this approach to show that food spending has fallen dramatically over time as a share of a household’s budget, including since the early 1980s. But perhaps that approach is flawed. Maybe housing has got more expensive, so families are cutting back on food spending to accommodate for that fact, but they are getting less or lower quality food.

For another approach, I will use Average Price Data for grocery items from the BLS CPI series. Note that I am using actual average retail price data, not prices series data, which means there are not adjustments for quality changes or substitutions. No funny stuff, just the raw price data (the only adjustment is if product sizes changes, which of course we want them to do, so we aren’t fooled by shrinkflation — so BLS uses a constant package size, such as 1 pound for many items or a dozen eggs, etc.).

The items I have chosen out of the 150-plus price series are the 24 items which are available in both 1980 and 2024. There may be some biases by doing this, but in general BLS is continuing to collect data on things that people continue buying. So it’s the best apples-to-apples comparison we can do (note that there are no apples in this list! Apples are tracked in the CPI, but there is no continuous price series from 1980 to 2024 for one apple variety).

How best to compare prices over time? Rather than “adjusting for inflation,” as is common in the popular press and by some economists, a better approach that I and other economists use is called “time prices.” Time prices show the number of hours or minutes it would take to purchase the good in two different years, using some measure of wages or income (I will use both average and median wages in this post). By looking at prices compared with wages for individual items, we can see whether each items as well as the entire basket has become more or less affordable.

Here is what time prices for these 24 items look like if we use average wages (I use a series that covers about 80% of the workforce, but excludes supervisors and managers). For this chart, I use prices in April 1980 and April 2024, since there is some seasonality to some prices (and April 2024 is the most recent price and wage data available, so it’s as current as I can get).

The chart shows that for 23 out of the 24 items, it takes fewer minutes of work to buy the items in April 2024 than it did in April 1980. For many items, it is a huge decrease: 13 items decrease by 30 percent or more (30 percent is also the average decrease). And while we once again might be concerned by selection bias of the goods, we have a nice variety here of proteins, grains, baking items, vegetables, fruits, snacks, and drinks. Unfortunately for the bacon lovers out there it is the one product going in the other direction, but there are still a variety of other proteins that have become much more affordable (pork chops are much cheaper!).

Here’s one way in which the image of the lady shopping wasn’t wrong: you could get a basket of groceries for about $20 in 1980. The basket I’ve put together (which is obviously different from the woman’s basket, but you work with the data you have) would cost $27 if you bought the package sizes BLS tracks (e.g., one pound for most of the meats and produce). In 2024, that same basket would cost $84. That’s 3 times as much! But since wages are over 4 times higher, the family is better off and groceries are, in a real sense, more affordable.

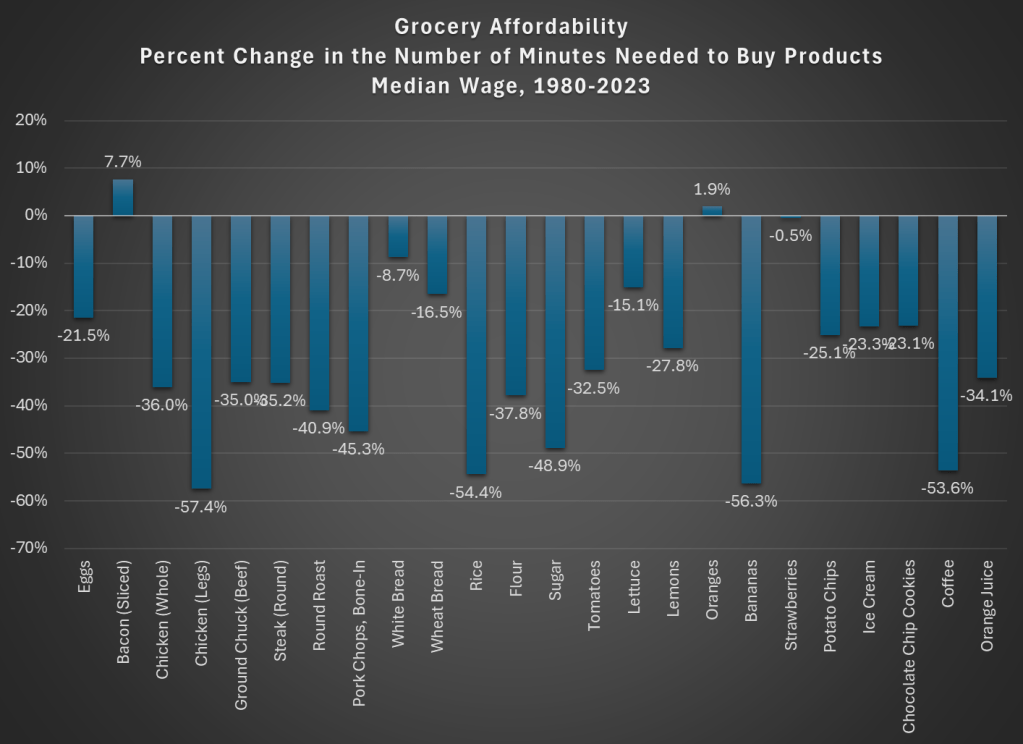

Speaking of wages though, is my chart perhaps biased because I’m using the average wage? What if we used another measure, such as the median wage? For that, I can use the EPI’s median wage series (which comes from the CPS), and I also converted it to a nominal wage for 2023. This wage data is only available annually, with the most recent being 2023, so I will also use 2023 price data for this chart (note: for oranges and strawberries, I use the second quarter average price, since they weren’t available year round in 1980 — another subtle example of growing abundance and prosperity today).

The immediate thing you will notice is that there isn’t much difference between the average wage chart. Bacon is still less affordable. We know have oranges being slightly less affordable and strawberries being basically the same, though keep in mind as I mentioned above the chart that these weren’t available year-round in 1980.

But other than bacon and those seasonal fruits, everything is more affordable in 2023 than 1980. The average decrease is the same as the prior chart: 30 percent fewer minutes of work at the median wage to purchase this basket of goods, with 13 of the 24 items decreasing by more than that 30 percent average. The reason for this similarity is that both the average and median wages as measured by these series are more than 4 times higher than 1980.

But are these 24 items representative of other grocery items that we don’t have complete price data in the public BLS series? They are probably pretty close. The unweighted percent change in the items from April 1980 to April 2024 was 201%. If we use the CPI Food at Home component, which includes many more items but also changes in composition as buying habits change, we see a slightly larger 255% increase. But that is still less than wages have increased since 1980 (by over 300% for both average and median wages). As our incomes rise, we will naturally switch to better and more expensive foods, which can explain the 255% vs 201% difference in price increases, but it also shows the BLS isn’t engaging in any funny business with the indexes: if they kept the basket of goods constant, price increases would be smaller.

While the rise in prices since 2021 might rightly make us nostalgic for the pre-pandemic era of prices, let’s not be nostalgic for 1980 grocery prices.

The BLS is or isn’t engaging in funny business? Check last sentence, penultimate paragraph.

LikeLike

What’s more, the percent decline in prices has a floor of 0%. There’s no crossing that boundary irl. So, halving a price thrice gets us down to -87.5%, whereas price increases have no such cap. Doubling a price thrice gets us 800%.

IOW, those price declines probably understate how we *feel* about the affordability improvements.

LikeLike

Statistics can be manipulated any way you want. My parents were both schoolteachers starting off their careers in 1978 they were making an annual salary of $36,800 per year. The average starting salary for a school teacher today is actually less than that, so you tell me how salaries have increased by 4x the amount. Show me a K-12 teacher today making a starting salary of $147,000 (4x$36,800). Youalso say that $84 will fill an entire shopping cart the other day I went food shopping and filled up three plastic bags which filled all of the entire basket at the top of the cart, nothing else. It cost me $71. So you tell me how I’m supposed to fill an entire cart for just $84. Trying to convince people that food expenditures are actually a smaller portion of their budget today than in 1980 it’s just laughable. At least try to make the article believable.

LikeLike

Your parents must have been very good teachers, because the average teacher salary in 1979 for all teachers (not just starting salaries!) was under $16,000

https://nces.ed.gov/programs/digest/d22/tables/dt22_211.60.asp

LikeLike