The seminal paper in the theory of human capital by Paul Romer. In it, he recognizes different types of human capital such as physical skills, educational skills, work experience, etc. Subsequent macro papers in the literature often just clumped together some measures of human capital as if it was a single substance. There were a lot of cross-country RGDP per capita comparison papers that included determinants like ‘years of schooling’, ‘IQ’, and the like.

But more recent papers have been more detailed. For example, the average biological difference between men and women concerning brawn has been shown to be a determinant of occupational choice. If we believe that comparative advantage is true, then occupational sorting by human capital is the theoretical outcome. That’s exactly what we see in the data.

Similarly, my own forthcoming paper on the 19th century US deaf population illustrates that people who had less sensitive or absent ability to hear engaged in fewer management and commercial occupations, or were less commonly in industries that required strong verbal skills (on average).

Clearly, there are different types of human capital and they matter differently for different jobs. Technology also changes what skills are necessary to boot. This post shares some thoughts about how to think about human capital and technology. The easiest way to illustrate the points is with a simplified example.

Moving Dirt

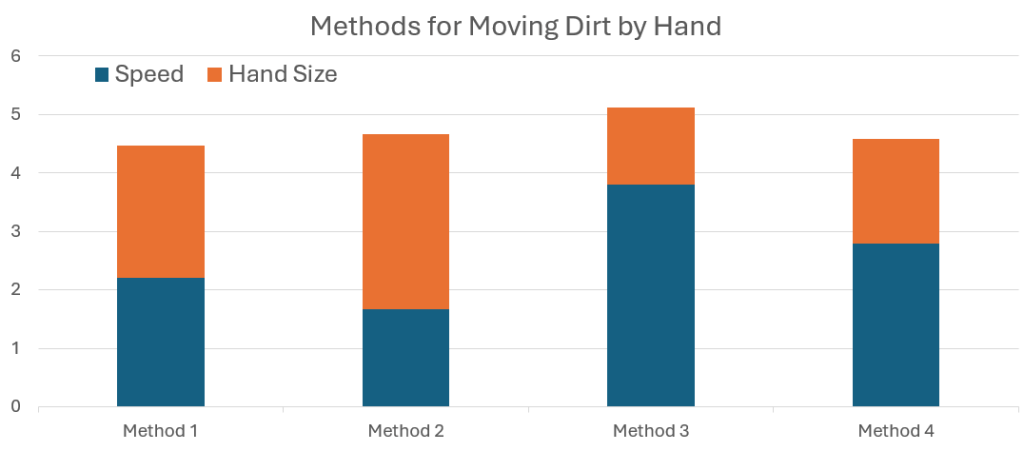

Humans have been moving piles of dirt around for as long as humans have existed. Imagine the most primitive case in which it’s just you and a pile of dirt. There are no tools or machinery and your job is to move the pile from one place to another. Let’s say that two things can matter: 1) how fast you can walk and 2) the size of your hands. Holding constant the mass of dirt and the time in which it is moved, there are a lot of ways one could succeed. You could leverage speed and move the handfuls quickly. Or, you could leverage the size of your hands and attempt to take bigger handfuls with each trip.

Above are some different combinations of speed and hand-size that can result in the same productivity. A difficulty with analysis is that it’s possible to move dirt in a lot of ways.* If people of identical productivity are characterized by the above distribution of human capital, then based on the empirics we’d think that there’s no productive advantage to either speed or hand size. In part, the problem exists because we’ve assumed away productivity differences. In real life, people sort into tasks according to comparative advantage. So, we’d observe the outcome of people with the above skill distribution rather than the entire set of possible skills that includes those of lower productivity. We don’t need to be fatalistic of course. Hand size is exogenous. But people can practice and improve their speed.

Things get interesting when we introduce technology. Say that the shovel is introduced. The availability of a shovel reduces the importance of hand size. In a sense, the physical capital of a shovel is a substitute for hand size. Holding productivity constant, small-handed fast people can suddenly move piles of dirt with the productivity that was previously not possible for them. Small-handed people competitively join the occupation and big-handed slow people experience more competition, having lost their comparative advantage they switch to different occupations.

Of course, there are many types of human capital that can be relevant to performing different tasks. Further, the characteristics that qualify as productive human capital is technologically contingent. Big hands are a type of human capital until the production function changes. Then, they provide a smaller advantage and we cease to consider them to be human capital at all. If capital is defined as ‘goods that produce other goods’, then human capital only qualifies as such if it augments production. Otherwise, it’s just a characteristic.

Therefore, the question is not whether human capital improves productivity. The question is ‘how does technology reward different human characteristics with the designation of productivity such that they qualify as human capital’. Some people are prompt engineers who perform queries on artificial intelligence. That might require a productive skill in some domains. But it’s not human capital at all for moving piles of dirt. It’s just a characteristic.

*Obviously, we don’t measure speed and hand-size on the same axis. It’d be more accurate and less concise to represent the bar chart as clustered rather than stacked.

Romer, Paul. 1990. “Human Capital and Growth: Theory and Evidence.” Carnegie-Rochester Conference Series on Public Policy 32 (March):251–86. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2231(90)90028-J.

Human Capital Investment and the Gender Division of Labor in a Brawn-Based Economy, Mark M. Pitt, Mark R. Rosenzweig, Mohammad Nazmul Hassan, American Economic Review, vol. 102, no. 7, December 2012, (pp. 3531–60)

Kim, Sun Hyung and Kwon, Dohyoung. “The Growing Importance of Social Skills for Labor Market Outcomes Across Education Groups” The B.E. Journal of Economic Analysis & Policy 24, no. 3 (2024): 847-878. https://doi.org/10.1515/bejeap-2022-0398