Yesterday on Twitter I shared a chart showing the age at first marriage for white men and women in the US, with data going back to 1880. I pointed out an interesting fact: at least for men, the age was essentially the same in 1890 and 1990 (27), though for women it was a bit higher in 1990 than in 1890 (by about 1 year).

This Tweet generated quite a bit of interest (over 800,000 impressions so far), and (of course!) a lot of skeptical responses. One skeptical response is that I cut off the data in 1990, when trends since then have shown continuously rising ages at first marriage, and by 2024 the comparable figures were much higher than in 1890 (by about 4 years for men and 6.5 years for women). In one sense, guilty as charged, though I only came across this data when looking through the Historical Statistics of the US, Millennial Edition, and that was the most current data available when it was printed. Here is a more updated chart from Census:

But there is another interesting fact about that data: the massive decline age of first marriage in the first half of the 20th century. Between 1890 and 1960, the median age at first marriage fell by about 3 years for men and 2 years for women. For men, most of the decline (about 2 years) had already happened by 1940. Thus, if we start from the low-point of the 1950s and 1960s (as many charts do, such as this one), it appears marriage is continuously getting less common in US history, while the fuller picture shows a U-shaped pattern.

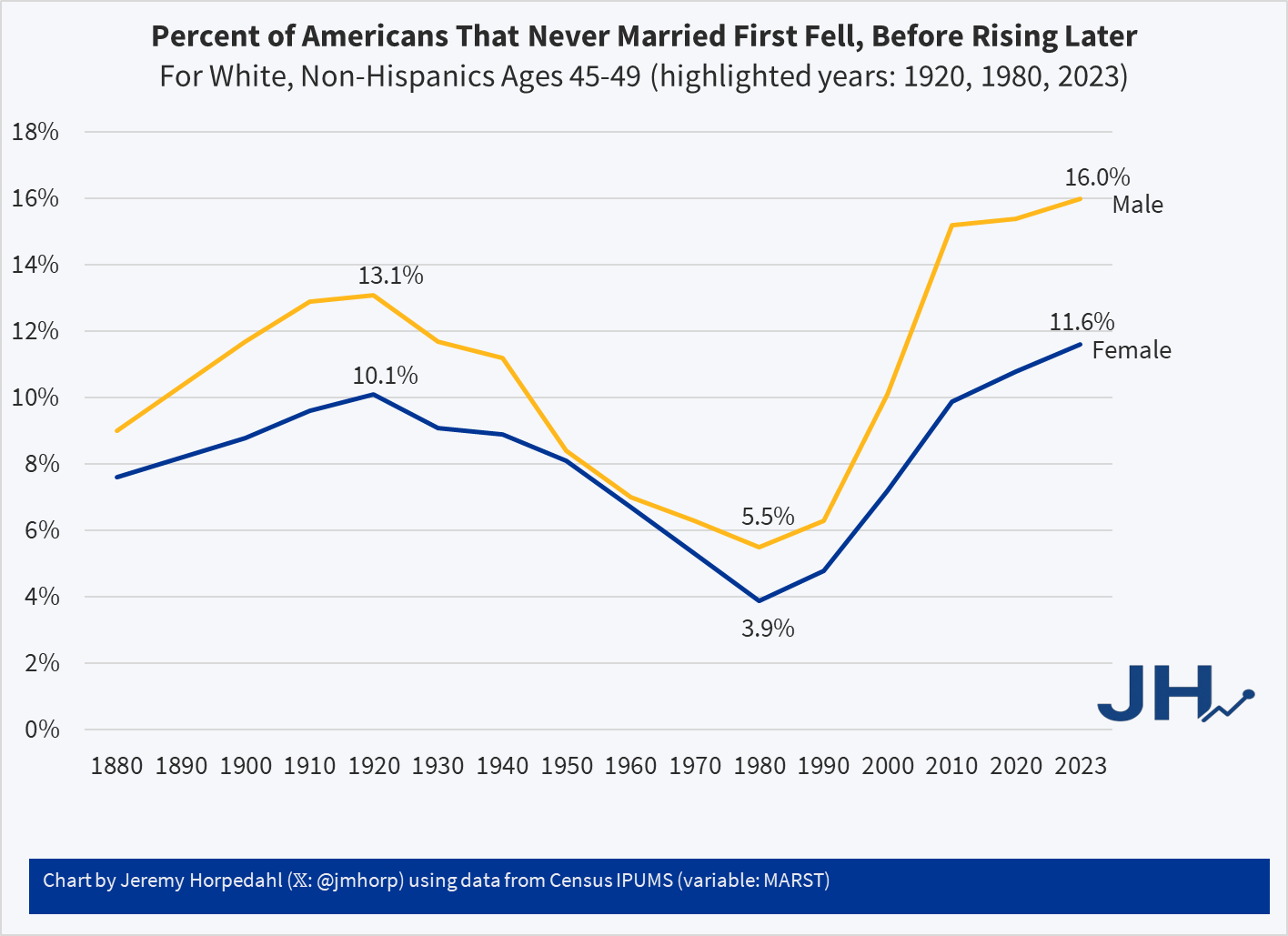

This same pattern shows up in another measure of marriage data: the percentage of people that never get married. If we look at White, Non-Hispanic Americans in their late 40s, the picture looks something like this (keen observers will note that the Hispanic distinction is a modern one dating from the 1970s, but Census IPUMS has conveniently imputed this classification back in time based on other demographic characteristics):

Looking at people in their late 40s is useful because, at least for women, they are past their childbearing years. And using, say, the late 50s age group doesn’t alter the picture much: even though some people get married for the first time in their 50s, it’s always been a small number.

Here we can see an even more dramatic pattern. 100 years ago, it was not super rare for people to never marry: over 1/10 of the population didn’t! But by 1980 (thus, for people born in the early 1930s), it was much rarer: less than 4% of women were never married (among White, Non-Hispanics). In fact, the peak in 1920 of 10% unmarried women wasn’t surpassed again until 2013! And it’s not substantially higher today than 1920 for women, especially when considering the full swing downward. Men are quite a bit higher today, though the 1920 peak of 13% wasn’t surpassed again until 2006.

For a measure that peaks in 1920, we might wonder if new immigrants are skewing the data in some way, given that this is right at the end of about 4 decades of mass immigration. But just the opposite: if we focus on native-born women, the 1920 level was even higher at 11.1%, which wasn’t surpassed until 2022, and even in the latest figures it is less than 1 percentage point higher than 1920.

Precisely why we observed this U-shaped pattern in marriage (both first age and ever married) is debated among scholars, though my sense among the general public is that it isn’t much thought about. Most people (from my casual observation) seem to assume that marriage rates and ages were always lower in the past, and that modern times are the outliers. But in reality, the middle part of the 20th century seems to be the outlier. The “Baby Boom” of roughly 1935-1965 is possibly better understood as a “Marriage Boom,” with more babies naturally following from more and younger marriages.

I will offer a speculation….my reading suggests that a key reason in the 1800’s that men did not marry until late or not at all is because they did not have a strong enough financial position (yet) to support a family, even though otherwise they wanted to marry. In the booming economy of 1950’s-1960’s, and before women started competing so much for jobs and competition from foreign manf heated up, I suspect nearly any capable man could find a reasonably well-paying job, enough to at least have a little house in a working-class neighborhood.

It might be interesting to explore the correlation between employment or real wages versus marriage age of men. It seems that marriage age declined smartly in the booming 1900-1930 period, esp as so many Americans migrated from the farm to town, where finding a decent job was easier, then. Then marriage age stagnated in the Depression 1930s.

LikeLike