Tariffs are going up to levels last seen in the 1930 Smoot-Hawley tariffs that helped kick off the Great Depression:

Tariffs are taxes- roughly, a national sales tax with an exemption for domestically-produced goods and services. I think the words make a difference here- “raising tariffs on countries who we run a trade deficit with” just sounds abstruse to most people, while “raising taxes on goods bought from firms in net-seller countries” sounds negative, but they are the same thing.

Of course, in this case the plan is to raise taxes to at least 10% on goods from all other countries even if they aren’t net-sellers, and raise taxes up to 49% on those that are. This is not a negotiating tactic. We know this from the math- the new tax formula uses net imports from a country rather than a country’s tariff rates, so a country could cut their tariffs on US goods to zero today and it wouldn’t necessarily reduce our “reciprocal” tariffs at all; at best it would reduce them to 10%. We also know it isn’t about negotiating because the administration says it isn’t. Their goal, obviously, is to reduce trade, not to free it.

They say they are doing this to bring manufacturing back to America and to promote national defense. But American manufacturers don’t seem happy. Even before the latest huge tax increase, trade war was their biggest concern:

The National Association of Manufacturers Q1 2025 Manufacturers’ Outlook Survey reveals growing concerns over trade uncertainties and increased raw material costs. Trade uncertainties surged to the top of manufacturers’ challenges, cited by 76.2% of respondents, jumping 20 percentage points from Q4 2024 and 40 percentage points from Q3 of last year.

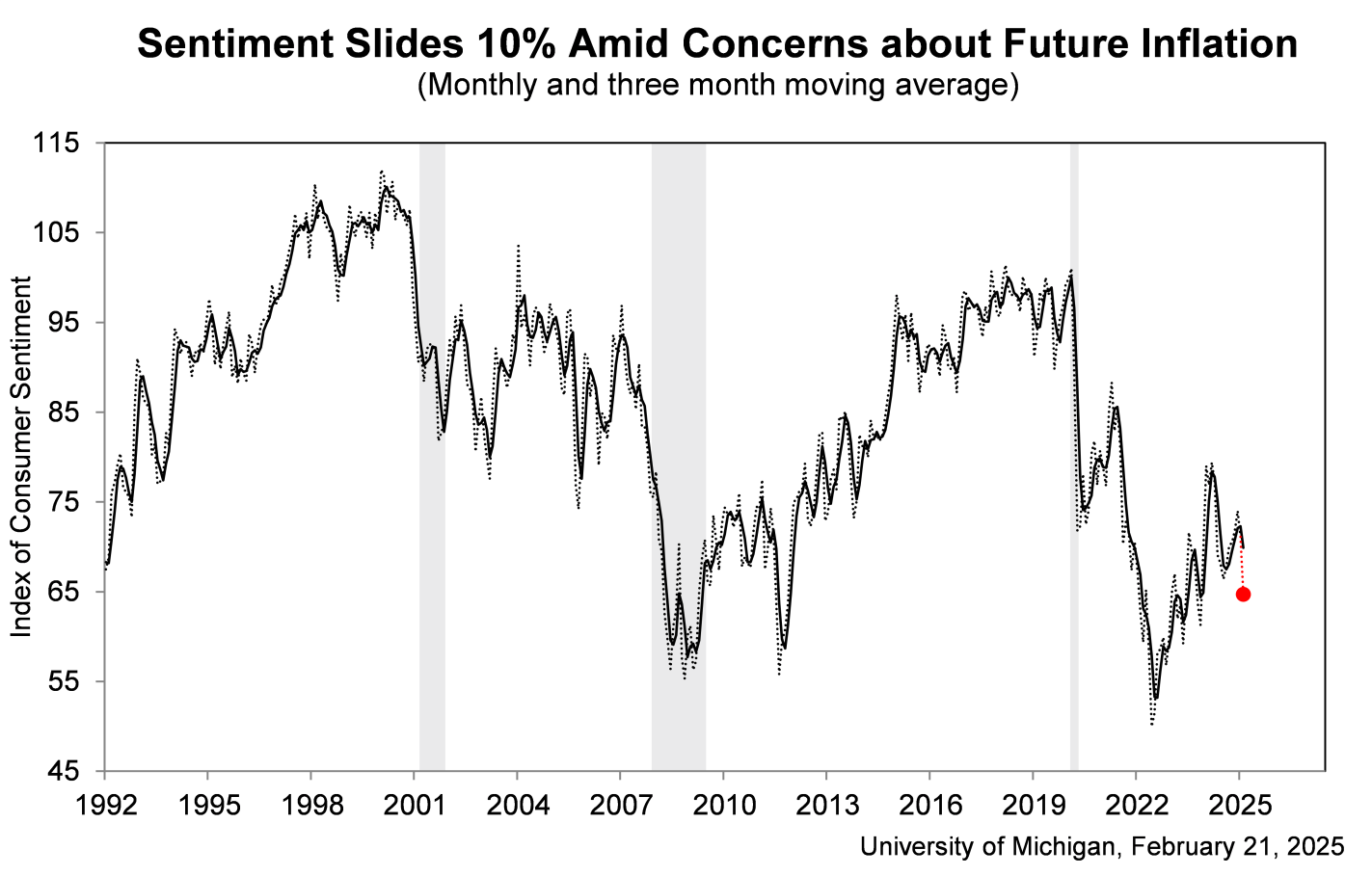

The National Association of Manufacturers responded to the latest tax increase with a negative statement; so even the one major group that might have benefitted from tariffs is unhappy. Foreign producers and US consumers will of course be very unhappy. I think Trump is making a huge political blunder alongside the economic one- he got elected largely because Biden allowed inflation to get noticeably high, but now Trump is about to do the same thing.

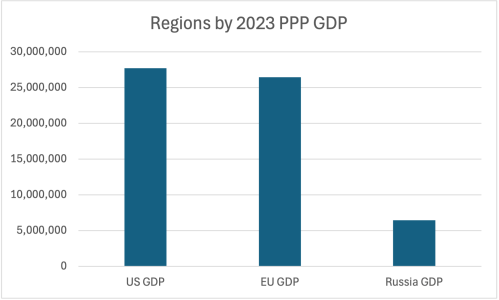

I also see this as a huge national security blunder. For tariffs on China, I at least see their argument- we should take an economic hit today in order to become less reliant on our peer-competitor and potential adversary. But the tariffs on allies make no sense- they are hitting the very countries that are most valuable as economic and/or military partners in a conflict with China, like Canada, Mexico, Japan, South Korea, Vietnam, India, and Taiwan (!!!). One of our biggest advantages vs. China has been that we have many allies and they have few, and we appear to be throwing away this advantage for nothing.

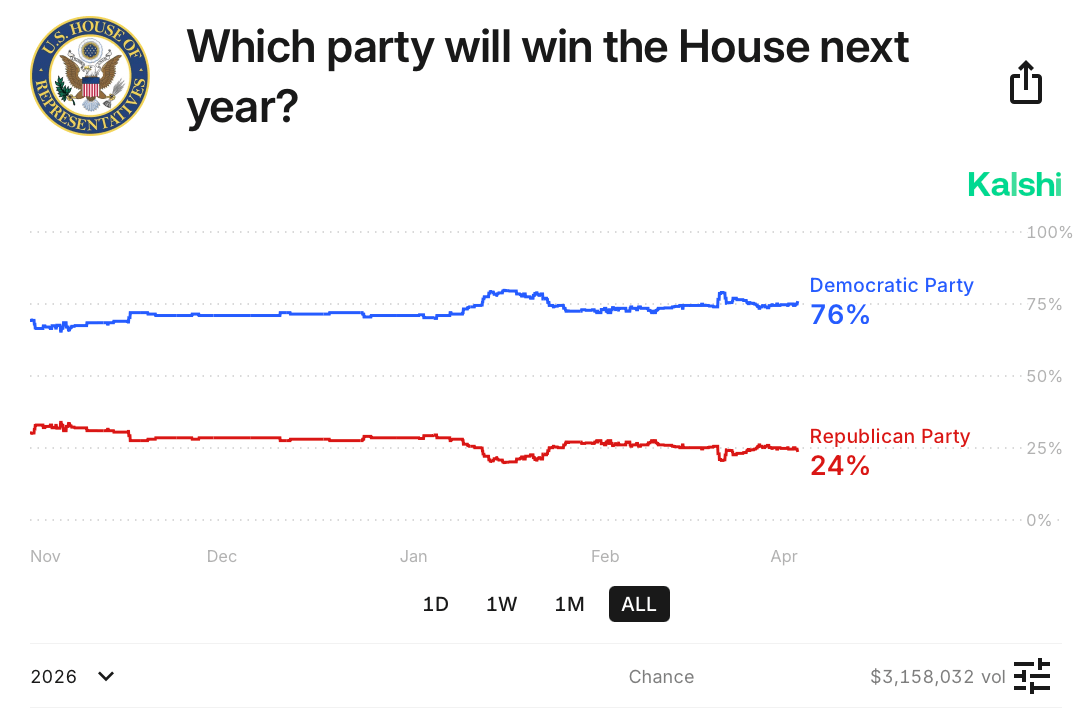

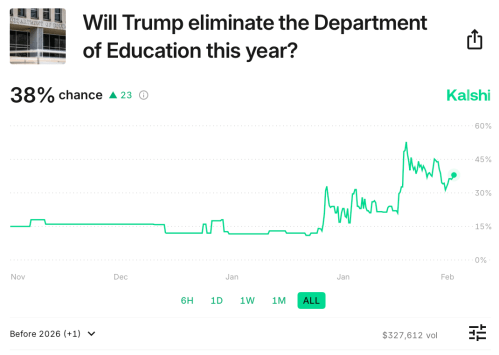

What can you or I do about this? Stock up on durable goods before the price increases hit. Picking investment winners is always hard, but things this makes me consider are gold, stocks in foreign countries that trade little with the US, and companies whose stocks took a big hit today despite not actually being importers. Finally, we can try nudging Congress to do something. The Constitution gives the power to levy taxes to the legislative branch, but in the 20th century they voted to delegate some of this power to the executive. Any time they want, Congress could repeal these tariffs and take back the power to set rates. I have some hope they actually will- just yesterday the Senate voted to repeal some tariffs on Canada, and more votes are planned. The alternative is to risk a recession and a wipeout in the midterms: