An Al Jazeera talk show called The Stream had me back again for

“Why subscriptions are taking over our lives”

along with journalist guest Sanya Dosani.

Our episode began with some clips from TikTok of young people expressing anger over feeling trapped in “the subscription economy.” Watch our show at the link above to see.

The subscription economy is a business model shift where consumers pay recurring fees for ongoing access to products/services (like Netflix, SaaS) instead of one-time purchases, focusing on “access over ownership” for predictable revenue. Gen Z feels upset that they are getting charged for subscriptions, some of which they simply forgot to cancel. They have nostalgia for the days of toting a zipper case of CDs onto the yellow school bus in 2004.

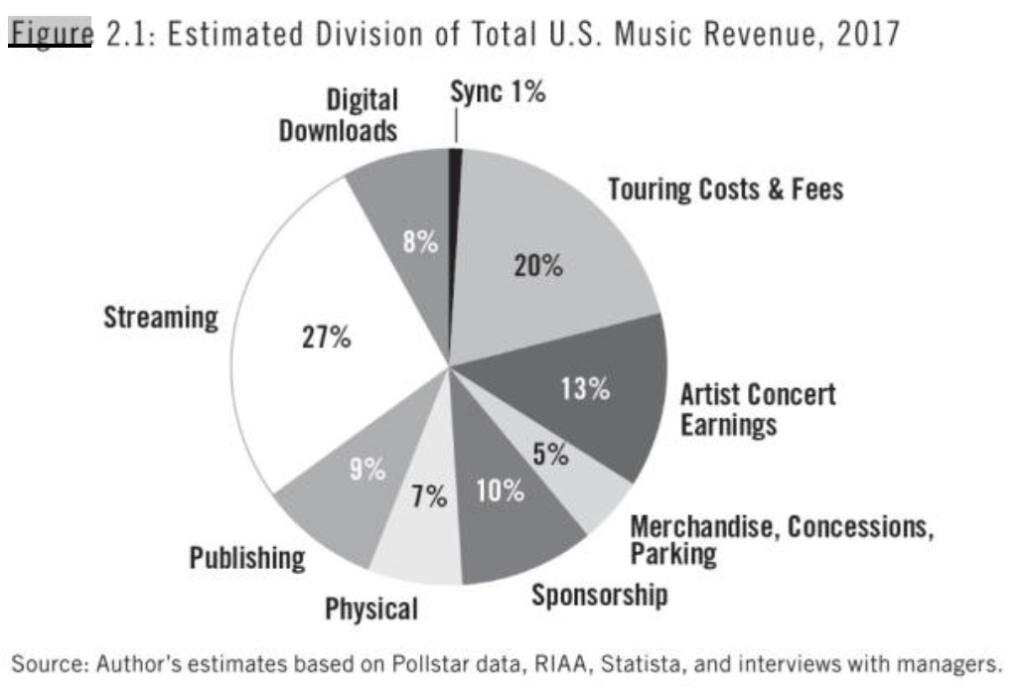

My commentary starts around minute 5:30 in the show. The first thing I point out is that, by and large, we have more entertainment available to us at a lower price than people did in that bygone era of mostly cable TV and physical discs. (This is a bit like the point I made on The Stream in March 2025 about how fast fashion represents more stuff for consumers at lower prices, which is good.)

In the episode, we discussed how people can still buy CDs today. Sanya Dosani made the point that, “there’s a place for buying and a place for renting.” Everyone should be aware of how cheap DVDs, books, and CDs are at rummage sales in the United States in 2025. You can get a music album for 50 cents. Some youths have (re)discovered that DVD players are cheaper than a year of streaming subscription costs.

Around minute 17, I got to bring up my research about intellectual property, digital goods, and morality.

I have two papers with Bart Wilson about taking and digital goods. In 2014, we published “An Experiment on Protecting Intellectual Property”.

And now we have a new working paper titled “You Wouldn’t Steal a Car: Moral Intuition for Intellectual Property” that makes a clean comparisons between the taking of rivalrous physical goods versus nonrival digital goods.

We find that people do not feel bad about taking the digital goods, or “pirating.” We even find that, in a controlled experiment with no previous context for what we might call intellectual property protection, the creators of these digital goods do not call such taking stealing either. It seems to be understood that folks will take and share if they can.

The proposed reason for artificially restricting the taking and resale of intellectual property is that creators need a way to profit from providing a public good. (Intellectual property rights in the U.S. Constitution are covered by Article I, Section 8.)

I said in the interview, “If you were able to just give a song to all of your friends, you probably would, and then that artist might not be able to make songs the next year.”

Thus, I suggested, “The subscription economy is a reaction to the fact that most people don’t view it as wrong to take things they can take and not necessarily pay for them. Companies had to find a new way to be able to make money and stay in business.”

I’ll clarify that I have not done quantitative research to prove that subscription models emerged causally because of pirating. I’m speculating. Another side to this is that people simply want to stream and companies are providing exactly what people want (despite the complaints circulating on TikTok). People reminisce about the “golden days” of early Netflix, but most people forget that the company was losing money at that time. Media production and distribution companies have to make money to stay in business.

At the end, the host asked me, “… what does it mean for who we are as humans, more of an existential question, where we are going with this age?”

That’s a deeper question than you might expect for a conversation about CD-ROMs. However, people do care about having some tangible form of art about them. Think of the ancients buried alongside beads and dolls. Netflix will never be the only thing that people want. As for Gen Z being upset about convenient Spotify, “what does it mean for who we are” has got to be part of it.

References:

“An Experiment on Protecting Intellectual Property” (2014) with Bart Wilson. Experimental Economics, 17:4, 691-716.

“You Wouldn’t Steal a Car: Moral Intuition for Intellectual Property,” with Bart Wilson

As an aside, furthermore, I’ll say here on the blog that Gen Z is by some measures the most entertained generation in history. For spiritual, not financial, reasons, I encourage them to cancel their subscriptions, take out their AirPods, and feel the silence and dread for a week.