Some highlights from reading the book What is Real? The Unfinished Quest for the Meaning of Quantum Physics*

Page 9 “The godfather of quantum physics, Niels Bohr, talked about a division between the world of big objects, where classical Newtonian physics rules, and small objects, where quantum physics reigned.”

The book has some drama, much centered around Einstein’s rejection of the Copenhagen interpretation.

The title of Chapter 2 is so excellent: “Chap 2: Something Rotten in the Eigenstate of Denmark”

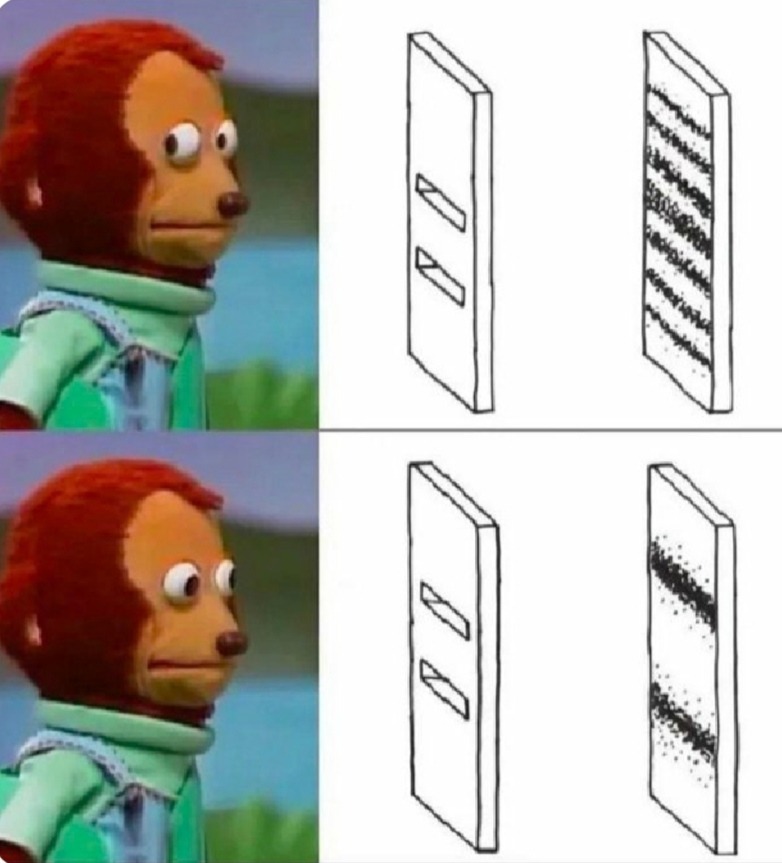

Pg 37 “But Max Born had discovered a piece of the puzzle that summer. He found that a particle’s wave function in a location yields the probability of measuring the particle in that location – and that the wave function collapses once measurement happens… The measurement problem had arrived.”

Pg 56 “Einstein rejected any violation of locality, calling it “spooky action at a distance” in a letter to Max Born.”

Pg 79 “By the end of the war, the Manhattan Project had cost the nation nearly $25 billion, employing 125,000 people at thirty-one different locations across the United States and Canada. Hundreds of physicists were called away from their everyday laboratory work … After the war ended, physics research in the United States never returned to what it was… Damned by their success … military research dollars poured into physics.”

Pg 82 “Research into the meaning of quantum physics was one of the casualties of the war. With all these new students crowding classrooms around the country, professors found it impossible to teach the philosophical questions at the foundation of quantum physics.”

Joy: The politics of physics in academia was interesting to me. I recommend this book to university economists on that merit alone.

Page 100 “the photons are deliberately messing with you”

Experimentalists take note, page 104 “The story that comes along with a scientific theory influences the experiments that scientists choose to perform”

Joy: Having no internet greatly slowed down the spread of the correct ideas. However, eventually, over the course of a few decades and with a few career casualties, the more correct information did seem to influence the consensus.

Joy: I’m used to economists having very basic and sometimes heated disagreements. One might say that issues in economics are a bit more subjective than a topic in the physical sciences. However, with quantum physics turning out to be so weird, there are also heated disagreements among the physicists.

An equivalent book for economics might be Grand Pursuit by Sylvia Nasar.

Pg 108: “Bohm’s theory had also appeared during the height of Zhdanovism, an ideological campaign by Stalin’s USSR to stamp out any work that had even the faintest whiff of a conflict with the ideals of Soviet communism.”

Pg 124: “This universal wave function, according to Everett, obeyed the Schrödinger equation at all times, never collapsing, but splitting instead. Each experiment, each quantum event… creating a multitude of universes…”

*Thanks to Josh Reeves and Samford University for buying me the book.

Related previous posts: Is the Universe Legible to Intelligence?