When we make drugs illegal but continue to buy them in huge amounts, we make the world unstable. That’s only a small part of what is going on right now, but it’s worth saying.

Politics

Preferences for Equality and Efficiency

Most people would consider both equality and efficiency to be good. They are “goods” in the sense that more of them makes us happier. However, in some situations, there is a trade-off between having more equality and getting more efficiency. Extreme income redistribution makes people less productive and therefore lowers overall economic output.

Examining the preferences people have for efficiency and equality is hard to do because the world is complicated. For example, a lot of baggage comes along with real world policy proposals to raise(lower) taxes to do more(less) income redistribution. A voter’s preference for a particular policy could be confounded by their personal feelings toward a particular politician who might have just had a personal scandal.

With Gavin Roberts, I ran an experiment to test whether people would rather get efficiency or equality (paper on SSRN). Something neat that we can do in a controlled lab setting is systematically vary the prices of the goods (see my earlier related post on why it’s neat to do this kind of thing in the lab).

One wants to immediately know, “Which is it? Do people want equality or efficiency?”. If forced to give a short answer, I would say that the evidence points to equality. But overly simplifying the answer is not helpful for making policy. The demand curve for equality slopes down. If the price of equality is too high, then people will not choose it. In our experiment, that price could be in terms of either own income or in group efficiency. We titled our paper “Other People’s Money” because more equality is purchased when the cost comes in terms of other players’ money.

The main task for subjects in our experiment is to choose either an unequal distribution of income between 3 players or to pick a more equal distribution. Given what I said above that people like equality, you might expect that everyone will choose the more equal distribution. However, choosing a more equal distribution comes at a cost. Either subjects will give up some of their own earnings from the experiment or they will lower the total group earnings. As is true in policy, some schemes to reduce inequality are higher cost than others. When the cost is low, we observe many subjects (about half) paying to get more equality. However, when the cost is high, very few subjects choose to buy equality.

This bar graph from our working paper shows some of the average behavior in the experiment, but it does not show the important results about price-sensitivity.

Continue reading“Zoning Taxes” — The Cost of Residential Land Use Restrictions

Fascinating new working paper on why housing prices are so high in some markets, by Gyourko and Krimmel: “The Impact of Local Residential Land Use Restrictions on Land Values Across and Within Single Family Housing Markets.”

Key sentence from the abstract: “In the San Francisco, Los Angeles, and Seattle metropolitan areas, the price of land everywhere within those three markets having been bid up by amounts that at least equal typical household income.”

Economists, libertarians, and more recently “neoliberals” have long complained about land-use restrictions as a primary factor contributing to unaffordable housing. This paper provides some pretty solid data, at least for some housing markets.

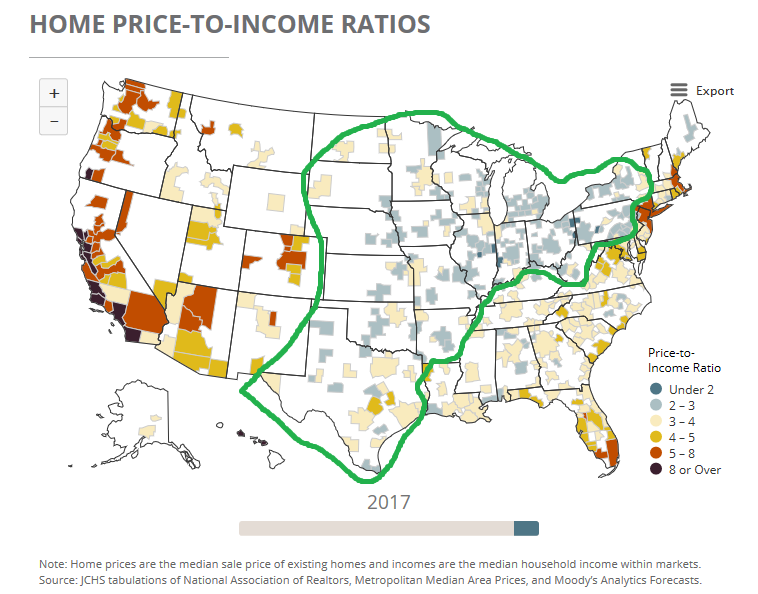

Here’s a key chart from the paper, Figure 5. Notice that there is a lot of heterogeneity across cities. In San Francisco, land use restrictions add roughly four times the median household income to the price of housing. But in places like Columbus, Dallas, and Minneapolis, there is essentially no zoning tax. That’s not because these cities have no land use restrictions! It’s just that they aren’t currently binding.

The paper also notes that “zoning taxes are especially burdensome in large coastal markets.”

This is similar to what I showed in a very non-scientific map that I created (in about 5 minutes) for a Twitter thread that I wrote in January 2020 on housing prices. In that map and thread I pointed out that there are still lots of fine US cities where you can purchase homes for roughly 3 times median income (a commonly used rule of thumb for affordability).

Will these cities continue to be affordable in the future? As demand increases, and supply-side restrictions remain in place, we would predict the same thing will happen to Columbus as happened to San Francisco. But probably not for decades.

So if you seek housing affordability, move to the Zone of Affordability! But let’s also work on reforming the rest of the country to make everywhere affordable.

Predicting the NYC Mayoral Race

Yesterday, co-blogger Jeremy asked “Should Andrew Yang Wait To Concede?” in the New York City mayoral race. He argued that while Yang finished 4th in 1st-place primary votes, the new Ranked Choice Voting system meant he could still win. This is of course true in theory- but today I argue it is very unlikely in practice.

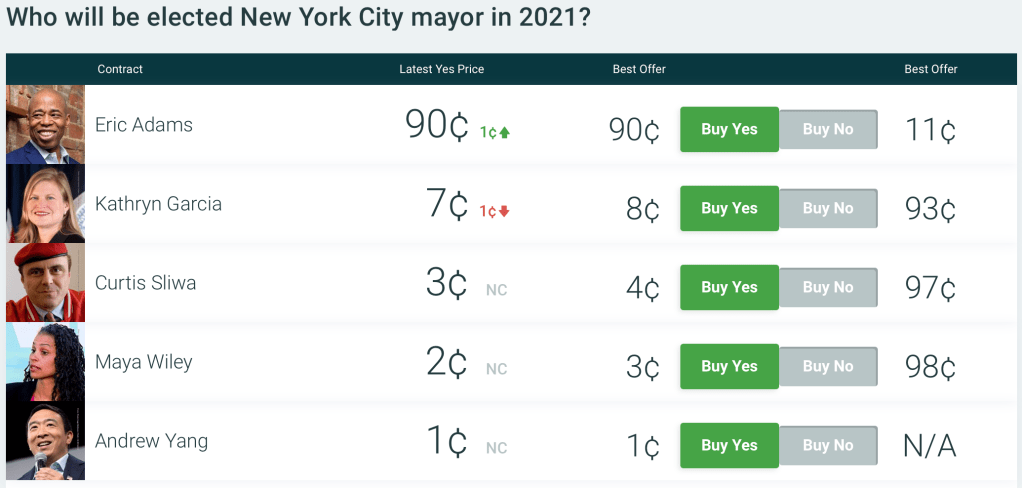

I say this not because I have scrutinized all the polls to predict the exact distribution of 2nd- and 3rd-place votes, or because I think I know more than Jeremy about political science or New York. Instead, any time I’m wondering about whether something will happen and I don’t have a strong opinion based on my own knowledge, I simply check what markets have to say. In this case, there are prediction markets bearing on this exact issue. The odds from PredictIt, shown below, have Adams (who finished with the most 1st-place votes, 32%) as the heavy favorite, with Yang reduced to an approximately 1% chance of winning.

But Jeremy is right to highlight that the Ranked-Choice system makes it less obvious who will win. You can see PredictIt traders still think that Garcia, who finished with 19% of 1st-place votes, is substantially more likely to win than Wiley, who finished with 22% (though the new system didn’t matter in the Republican primary, where Sliwa won with a clear majority of 1st-place votes).

Crypto-based betting platform Polymarket has actually closed their market for Yang already, declaring that he lost, though they agree with PredictIt that the overall election isn’t over and that Garcia still has a real chance despite coming in 3rd for 1st-place votes.

Of course, prediction markets aren’t perfect- they are certainly less accurate (easier to beat) than the stock market, as my track record of betting in both shows. But they make for a great first approximation on subjects you don’t know well, and if you think you do know better, they offer you the chance to make money and to make the odds more accurate. If you think Yang will still win, you can go bet on PredictIt and potentially 100x your money. Or if you think this ranked choice stuff is nonsense and Adams obviously won, you can pick up an easy 10% return. Or if you’re like me in this case, you can stay out of it, take a quick glance at the markets, and get a good idea of what is likely to happen without having to read the news or the pundits.

Should Andrew Yang Wait to Concede?

Yesterday New York City held their mayoral primary elections. This was an exciting event for election system nerds (political scientists and public choice economists) because NYC is now using a form of ranked choice voting to determine the winner.

While this is not the first place in the US to use RCV (Maine, Alaska, and a handful of cities use it), it is still notable for a few reasons. First, this is America’s largest city. Second, there are a lot of viable candidates, which makes RCV especially interesting and useful.

Specifically, NYC is using a form of voting called instant runoff. There are currently 13 candidates, and voters indicate their top 5 in order. If no one has a majority (>50%) of the votes, then the rankings entered by voters come into play. And indeed that is what happened yesterday.

On the first round, only counting first place votes, Andrew Yang came in 4th with just under 12% of the votes. So last night he conceded.

But should Yang have conceded? Maybe not! Let’s explore how instant runoff works.

Continue readingEndless Frontiers: Old-School Pork or New Cold War Tech Race?

The Endless Frontiers Act passed the Senate Tuesday in a bipartisan 68-32 vote. What was originally a $100 Billion bill to reform and enhance US research in ways lauded by innovation policy experts went through 616 amendments. The bill that emerged has fewer ambitious reforms, more local pork-barrel spending, and some totally unrelated additions like “shark fin sales elimination”. But it does still represent a major increase in US government spending on research and technology- and other than pork, the main theme of this spending is to protect US technological dominance from a rising China. One section of the bill is actually called “Limitation on cooperation with the People’s Republic of China“, and one successful amendment was “To prohibit any Federal funding for the Wuhan Institute of Virology“

Continue readingHistory according to Polybius

It’s unusual for me to sit down on a weekend morning and read *literally checks notes* Polybius. This was assigned to me for a seminar. Here’s his proposal for the inevitable endless cycle of human leadership structures:

- Some humans are still alive. They band together because they are too weak to survive alone.

- A strong man who bravely defends the group in his youth becomes a monarch. “Kingship” is the next progression. Polybius assumes that people could consent to be under the leadership of a powerful and noble man.

- The king has children. The people venerate the descendants of the good king, but these princes and princesses will be spoiled and selfish. The princes “gave way to their appetites owing to this superabundance…” Thus, kingship becomes tyranny.

- Nobles overthrow the tyrants, and so become aristocrats. “But here again when children inherited this position of authority from their fathers, having no experience of misfortune and none at all of civil equality and liberty of speech… they abandon themselves to greed… and… rape…” The aristocracy becomes a corrupt oligarchy.

- Democracy emerges when people have “killed or banished the oligarchs” and the people remember being mistreated by kings. How does Polybius think democracy ends? Once again, it’s the new generation and the corruption they indulge in. Where do they end up? “… democracy in its turn is abolished and changes into a rule of force and violence.”

- There are two ways to get back to stage 1 monarchy. Life in the decline of a democracy is chaotic enough that people willingly back a strong man to protect them. Alternatively, he presents a “floods, famines, failure of crops… all arts and crafts perish…” scenario. A natural disaster, regardless of what stage in the political cycle humans were at before, will position the survivors to start again at monarchy.

Wait for the Lower Cost Version of Policy

I’ve written previously about initial US state compulsory schooling laws in regard to literacy and in school attendance rates. I ended with a political economy hypothesis. Here’s the logic:

- Legislators like lower costs, all else constant (more funding is available for other priorities).

- Enforcing truancy and educating an illiterate populous is costly.

- Therefore, state legislatures that passed compulsory attendance legislation will already have had relatively high rates of school attendance and literacy.

That’s it. Standard political economy incentives. But is it true? Well, we can’t tell what’s going on in politician heads today, much less 150 years ago. Though, we can observe evidence that might corroborate the story. In plain terms, consistent evidence for the hypothesis would be that school attendance and literacy rates were rising prior to compulsory schooling legislation. The figures below show attendance and literacy rates for children ages 10 to 18.

Continue readingPolitical Poverty is a Choice

Political drama was about to happen and then it didn’t. Across the country, deep and insightful thinkpieces were left unfinished, relegated to the folder for things writers hope will become future brilliance but definitely never will.

The Big Covid Stimulus Bill was about to fall short by a single vote, with Senator Joe Manchin (D-West Virginia) threatening to break against party lines. It was a disaster… until it wasn’t. A political catastrophe, evidence that the Democrats were a failed coalition once again humbled by their ruthless coordinated opposition… until it wasn’t.

So what was the source of this unforeseeable political miracle? Joe Biden’s long-running political strategy of asking people what they wanted, keeping promises, and not being a d*ck.

As much as I want to roll with three paragraphs of clever wordplay referencing stratagems and gambits, the obvious point to be made is that Biden has decades of political capital that the entire Democratic party is currently able to leverage. In contrast, the Republican Party is currently fronted by a Senator who has broken every political norm for short/medium run political gain, while bearing the brand of a career grifter who spent decades opting not to pay his contractors, employees, or lenders.

I’m not much for making forecasts or predictions, so here’s my predictive forecast for the Republican party: they don’t matter and won’t for years.

Make no mistake: their politics still matter a great deal. White ethno-nationalism has a real foothold in chunks of the electorate all over the country, evangelical Christians remains one of the most influential voting blocks, and the US system remains weighted towards the preferences of rural voters. Rather, what I mean is that the institution of the Republican Party no longer brings much to the political bargaining table. The party has spent down decades of political capital and no recourse to trust in their reputation to solve collective action problems. The bill has finally come due for their spendthrift and short-sighted culture. As much as it may hurt our sympathetic sensibilities, we owe it to them to let them learn from this experience and, after a few decades of trustworthy behavior and political saving, they should be able to pull their party up by their bootstraps.

In four years, two with control of all three branches, the GOP was never ever able to pass legislation as impactful on the US landscape as what the Democrats pulled off this week. The Republican party remains an efficient fundraising organizing and cultural brand for running a campaign, no doubt. There’s not going to be a third-party usurping of their status as one of the two dominant parties, at least not any time particularly soon. But as far as the legislative marketplace is concerned, the Republican party is dead broke.

Broad Base, Low Rates: Every US State Fails on Good Sales Tax Principles

In a previous post, I contrasted the income and property taxes, but I left out the other important tax: the retail sales tax. So let’s rectify that omission.

The retail sales tax is like the “Little Engine that Could,” delivering a steady stream of revenue to governments, while mostly staying out of the passionate debates surrounding the income and sales taxes. About 23% of state and local tax revenue comes from general sales taxes in the US, roughly equal to income taxes, and if you include selective sales taxes it’s slightly larger than the property tax share.

But there’s a problem with sales tax. The sales tax “base,” basically the extent of economic activity that the base covers, has been shrinking. A lot. As Jared Walczak has recently written, in just the past 20 years the “breadth” of the sales tax (how much of the potential base it covers) has fallen from about 50% to 30%.

As Walczak also notes, there are seven or so broadly agreed on principles of sales taxes, but I would say there are two primary ones (the first two on his list):

- An ideal sales tax is imposed on all final consumption, both goods and services.

- An ideal sales tax exempts all intermediate transactions (business inputs) to avoid tax pyramiding.

But US states violate these two principles in various ways, leading to (oddly enough) a tax base that is simultaneously too narrow and too wide. Why is this?

Continue reading