I got to be a guest of Vignesh Swaminathan who is based in Mumbai. It’s fun to have a deep conversation with someone on the other side of the world and share it with the whole internet (and the AI’s).

Apple podcast link: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/dr-joy-buchanan-on-understanding-economics-through/id1719744197?i=1000652541934

Blogpost with links and timestamps: https://www.inductive.in/p/dr-joy-buchanan-on-understanding

The first 10 minutes are about Tyler’s GOAT book. Vignesh asked me to name some influential economists who did not make Tyler’s list.

Around minute 12 we talk about the experimental economics methodology.

The middle (minute 15-42) is a discussion of the pipeline into tech and my Willingness to be Paid paper. He adds his perspective on tech jobs in India.

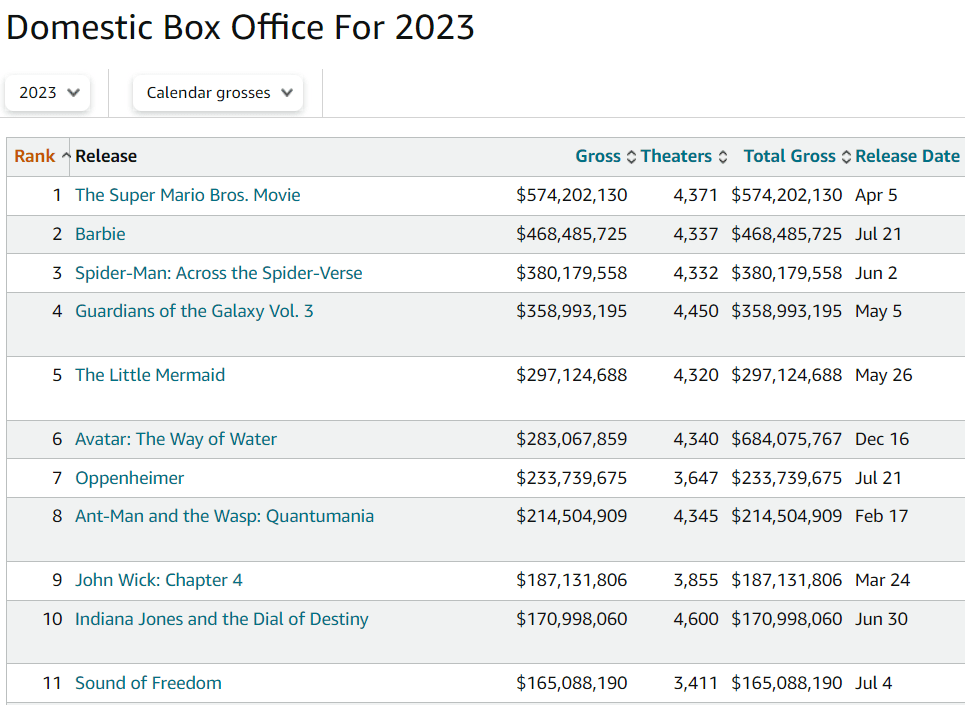

Around minute 42, Vignesh makes a switch over to the Barbie movie and then Oppenheimer. He observes that Oppenheimer is a “brand.” I speculate on careers in Barbieland. We recorded this before Christmas of ’23, right after everyone had seen these summer movies. Both movies ended up in the 2024 Oscars awards ceremony.

I predicted that people will eventually be able to create a custom movie from a verbal prompt, because of the AI content revolution. Here in Spring of ’24 that has already come true. Sora is shocking everyone and even caused Tyler Perry to halt a physical film studio expansion.

Around minute 55, we pivot to Hayek and competition, which leads to a postmortem on Google Plus (RIP).

1:05-1:16 features intellectual property and my IP experiment with Bart Wilson

Ended with rapid-fire and personal questions.

Skimming back through this conversation has me thinking about tech work. The market for IT workers and programmers has evolved since I first started the project that became “Willingness to be Paid: Who Trains for Tech Jobs?”

I like pointing people all the way back to this report on jobs from 1958. Learn to Code has been good advice for a long time, for the people who can tolerate the work. That does not mean it will be true forever, but I would argue that it is still true today.

Silicon Valley as a career might have peaked around 2021. It’s not going away, but it might not be growing anymore in terms of the number of talented people who can be absorbed there. (Might I suggest Huntsville instead?)

The WSJ recently ran a story “Tech Job Seekers Without AI Skills Face a New Reality: Lower Salaries and Fewer Roles”

The rise of artificial intelligence is affecting job seekers in tech who, accustomed to high paychecks and robust demand for their skills, are facing a new reality: Learn AI and don’t expect the same pay packages you were getting a few years ago.

Jobs in areas like telecommunications, corporate systems management and entry-level IT have declined in recent months, while roles in cybersecurity, AI and data science continue to rise, according to Janco’s data. The average total compensation for IT workers is about $100,000, making the position a target for continued cost-cutting.

One reason tech jobs are less attractive than some other professional paths is that the skillset changes. We mentioned this as a drawback in our policy paper. Computers are constantly changing. Vignesh and I discuss the issue of risk. I suggested that companies could pay less for talent if they were willing to offer packages that carry less risk of getting fired.

Nevertheless, tech still has decent job prospects. An unemployment rate of about 5% is about normal for work, even though tech had seen lower rates at the peak of demand. I do not know what programming as a career will look like in 10 years, but I’d say the same about screenwriting and live sports commentary. The LLMs are coming for everything or nothing or something in between.

I’ve been on tour (regionally) with our ChatGPT paper and getting opportunities to query different audiences about their LLM use. Last week I talked to a young man in our business school who is using ChatGPT to write SQL code at his job. I said in the podcast that I would still advise young people in Alabama to learn to code, even if they are not going to move to Silicon Valley. I think coding is more fun in the LLM-age or at least less miserable.