Are you tired of hearing about revisions to jobs data? Well, there was another hot one released by BLS yesterday. Known as the “preliminary estimate of the Current Employment Statistics (CES) national benchmark revision to total nonfarm employment,” this change isn’t yet incorporated into the official jobs data. But it will, possibly slightly modified, be included with the January 2026 jobs release, altering jobs data back to April 2024. It is part of the normal annual process of reconciling the monthly, survey-based jobs data with the near-universe data from unemployment insurance records. Normally, this is a quiet affair, especially the preliminary estimate which is just giving a heads up to researchers about what will be coming in a few months.

I wrote about these preliminary figures last year, when the initial estimate was a negative revision 818,000 jobs. When revised and actually incorporated into the data, it was a somewhat smaller 598,000 jobs, which I then used in a post just last month to show that BLS hasn’t been getting worse at estimating jobs. If anything, they have been getting better. Yesterday’s report showed that the revision could be negative again, this time 911,000 jobs. That’s a little bigger than last year, but maybe it will end up being smaller in the final number. So, no big deal again?

Maybe not. The 911,000 jobs revision would actually be much larger than last year’s revisions because it’s coming on top of a slower growing labor force already. The initial report for March 2024 showed 2.9 million jobs added in the past year, so the 818,000 revision was a much smaller share than this most recent data, since the March 2025 initial report showed just 1.9 million jobs added in the prior year. And the March 2025 jobs numbers have already been revised down by over 100,000 jobs since the initial report, meaning that potentially half or more of the initially reported job gains would be lost due to the revision, as opposed to about 20 percent last year.

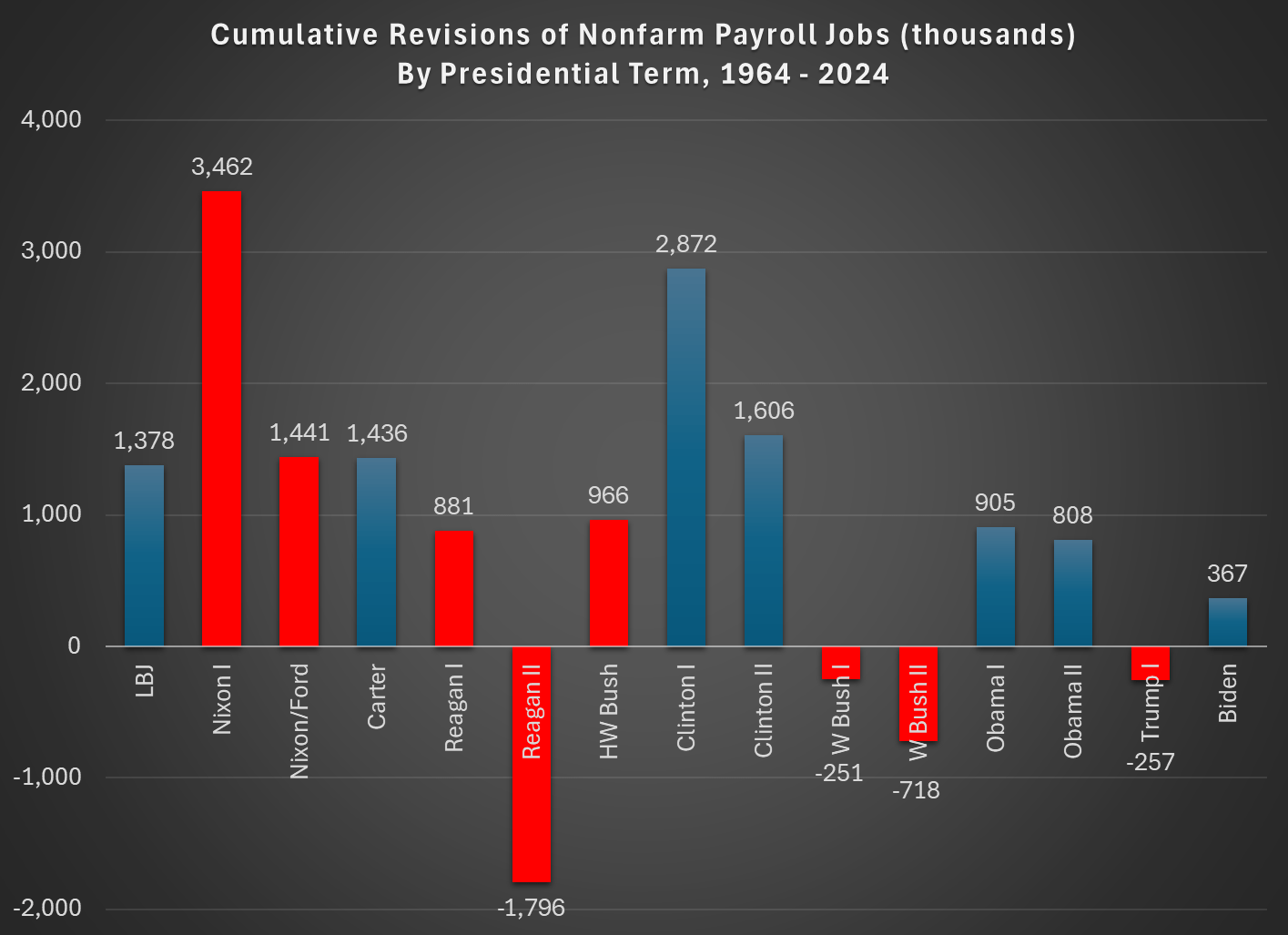

Is losing half of the job gains large? Yes. In fact, almost unprecedented:

(note: I am trying out a new chart template. Let me know what you think!)

Continue reading